Folklore of Lincolnshire (2 page)

Read Folklore of Lincolnshire Online

Authors: Susanna O'Neill

Statue of Alfred Lord Tennyson, housed in Lincoln Cathedral gardens.

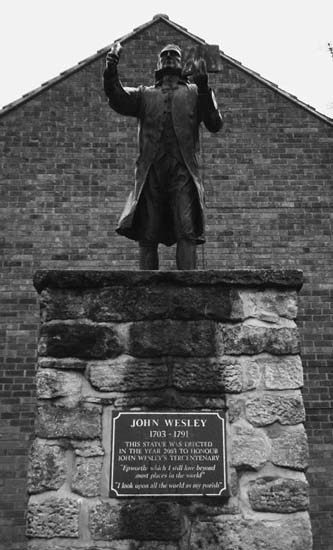

Statue commemorating John Wesley, situated towards the top of Albion Hill, Epworth.

The content of money making, marriage, love and property is all the better for being read in dialect!

Tennyson is not the only notable to claim a Lincolnshire heritage. John Whitgift, the Archbishop of Canterbury from 1583 to 1604, was born in Grimsby and William Byrd, the composer, was born in Lincoln in 1543. Everyone has heard that Margaret Thatcher’s humble origins stem from an upbringing in Grantham, and the poet Elizabeth Jennings (1926-2001) was born in Boston. King Henry IV was born at Bolingbroke Castle and was often known by the name Henry Bolingbroke.

Other famous names include Hereward the Wake, William Cecil, Sir Isaac Newton, Sir John Franklin, Sir Joseph Banks, Chad Varah, John Wesley, William Stukeley, Jennifer Saunders, Neil McCarthy – just to name a few.

The

Lincolnshire Poacher

magazine

9

quotes a source who talks of a postcard written by the young Winston Churchill in August 1887. He was staying on holiday

with his nanny in a boarding house in Skegness. The postcard was addressed to his mother and the lad was asking her for half a crown, but apparently on the reverse the nanny had written a note to the effect that he should not be sent any money as he had already wasted a good deal! This was not the last time Churchill visited Lincolnshire; he was invited many times to speak at different places around the county in the early 1900s, and sources say he had quite an affection for the place.

Lincolnshire even has two claims on King Arthur, according to Marc Alexander. One states that it was at Lincoln that King Arthur came ‘secretly upon Tholdric and fell silently upon the Saxons’.

10

The second tells that King Arthur fought a battle in the district of Lindsey, then known as Linnius.

The Lincolnshire Magazine

from the 1930s propounds this idea, mentioning a great soldier in Digby, although whether it is actually King Arthur or another is debatable:

At Chestnut Tree Corner, under the little triangle of green grass where the footpath goes off to the station, a great soldier lies buried with all his men. One day a man will come along who can see a silver tree growing there, and he will see this tree as he stands on Canwick Hill, a point twelve miles distant…when he gets to Chestnut Tree Corner he will find steps going down into the ground, which he will descend and there he will find this great soldier and his men asleep. He will awaken them and they will rise all up again and fight for the King at a time when they are sorely needed.

11

This story is prevalent all across Britain, most counties claiming the sleeping warriors, such as Craig y Dinas, Glamorgan or Alderly Edge, Cheshire or under Richmond Castle in Yorkshire, but to name a few, and so it is nice to see it included in Lincolnshire’s folklore.

Having been invaded and inhabited by various races throughout the centuries, several of Germanic stock, many of the placenames of Lincolnshire have traceable routes. Professor Stenton

12

studied particularly those of Danish origin. He states that the characteristic type of Danish name in Lincolnshire ends in ‘by’, an ancient word meaning ‘settlement’ or ‘village’ which, he explains, is why we have the term ‘bye-law’, originally referring to the local regulation of a village community. He then goes on to say that uncomplimentary nicknames are characteristic in Lincolnshire, for example: Scamblesby, ‘the village of the shameless one’; Scawby, ‘the village of the bald man’; Brocklesby, ‘the village of the man without trousers’; Sloothby, ‘the village of the good-for-nothing rascal’. Not all are uncomplimentary however, such as Somerby, ‘the village of a man who has taken part in a summer army’.

Those places ending in ‘thorpe’, such as Skellingthorpe, referred to a settlement smaller than the nearby village; ‘ing’ denoted low wet grass or pastures; ‘with’ meant a wood; ‘langworth’ was long ford; ‘worth’ referred to a small enclosure. Some examples of Anglo-Saxon endings to place names include ‘stead’, meaning place; ‘staple’, denoting a market; and ‘ley’ a meadow.

Lincoln Cathedral.

Many places were named after certain people or families such as Hagworthingham, which is said to have been the home of the descendents of Hacberd. Similarly Grainthorpe was believed to have been the village of a man named Geirmundr.

The study of place names is a complete project on its own, so will not be delved into further in this book, but it is a vast and fascinating subject to follow for those who are interested. It gives an insight into the history of our land, the peoples who dwelt there, the type of landscape which surrounded them and what importance they placed upon it. To try and view the land as it was in their times gives us a glimpse of what life was like for them and we begin to see how some of the folklore and legends originated.

Traditionally the capital of Lincolnshire, Lincoln, has a population of approximately 81,000 people. It was originally named Lindon, meaning ‘the pool’, as it was a settlement built by a deep pool along the River Witham. Later the Romans re-named it Lindum colonia, ‘Roman colony’, which eventually turned into what we now know as Lincoln. The city is teeming with history. One just has to walk down the main street to see how many interesting old buildings are left, without even mentioning the castle or the cathedral. The third largest in the country, the cathedral towers over the city, dominating the skyline. Legends abound around this colossal structure and ghost stories and folklore of the city are plentiful.

The county had a reputation for its wetlands and fens, as illustrated in this little ditty Mrs Gutch recorded for us for the early 1800s:

There is so much more, however, than the legendary boggy landscape. Described perfectly in

Brewer’s

Britain and Ireland

, Lincolnshire is:

…for the most part flat, and much of the south is taken up with the Fens, but it does manage to raise itself at least on to an elbow in two places, the Lincolnshire Edge (known locally as ‘the Heights’ or ‘the Cliff’), a limestone escarpment running east to west on which the city of Lincoln is situated, and the Lincolnshire Wolds, a range of chalk hills running northeast-southwest in the eastern part of the county.

14

And according to Jack Yates and Henry Thorold:

The long drainage ditches and narrow roads so characteristic of Lincolnshire.

The landscape is of strongly contrasted kinds – one long and level with two-thirds of every eyeful sky. Wide and splendid cloudscapes and a great expanse of stars at night…The other sort of scenery is hilly, the rolling country of the Wolds, which seem very high by contrast but never rise more than 550 feet and are like the

Downs, with beech plantations on their slopes and villages in their hollows and at their feet.

15

Well known for its farming, Lincolnshire is ‘overwhelmingly agricultural…the county supplies Britain with a cornucopia of vegetable…its pigs are famous…Lincolnshire sausages…’

Cumbrian and Lincolnshire sausages are two of the best known in the country but there were other farming traditions which made Lincolnshire famous. There is a specific Lincolnshire breed of sheep called Lincoln Longwool, larger and heavier than the Leicester, and also there is the Lincoln Red; a breed of red shorthorn beef and dairy cattle. There was once a breed of pig, the Lincolnshire Curly Coat, aptly named due to its woolly coat, but it has now died out.

Also known for its tremendous fishing industry, the Lincolnshire sailors and their wives have a tale or two to tell about life with the sea.

A community heavily reliant on agriculture, much of the Lincolnshire landscape encompasses fields upon fields of farmland.

We shall begin our journey through Lincolnshire’s store of tales and folklore by introducing the canny nature of the Lincolnshire folk through their shrewd tradition of decoy ducks.

16

They say that some Lincolnshire farmers used to breed ducks in a special way, for the specific purpose of betraying their fellow ducks! One source suggests there were up to forty such farms in the county, taking somewhere in the region of 13,000 birds via this method, in one season.

The decoy ducks were bred in specially designed ponds, where they were given much attention and care so that they became tame and fed from the farmer’s hand. When they were ready they were ‘sent’ abroad, possibly to Europe, where they met other ducks and enticed them back to Lincolnshire, in their ducky language, with tales of a wondrous life!

When the decoy ducks returned with flocks of followers, the men began to secretly feed the newcomers handfuls of grain in the shallows of the ponds. The decoy ducks were used to this and happily went to eat and soon their new friends copied, confident in their host’s judgement.

The grain was soon scattered in a wide open place and the ducks went there to eat it. Then it appeared in a narrower area, where the trees hung over like a tent. All the ducks now followed the food, feeling secure but unaware that there had been a large net placed in the foliage above their heads.