Flying Crows (26 page)

XXIV

RANDY

UNION STATION

1997

On the drive back to Kansas City, Randy remembered something from that day at the Kenwood residence, something the old man had said about his life at Union Station.

It led to Randy's going to Union Station the following afternoon.

One of the restoration contractor's men found the door in the back of the old Harvey House section on the east side of Union Station and unlocked it for him. He said the door opened to a stairway that would take him up and across to the south side where Randy wanted to go.

The guy, whose first name was Roy, had worked in the maintenance department of the old Kansas City Terminal Railway Company for around thirty years. The project managers had summoned him and his memory out of retirement to help them get started. They needed Roy to tell them where all the old switches, pipes, wires, systems, nooks, and crannies were.

“There are only a few lights up there that workâthat have bulbs in 'em,” said Roy, handing Randy a large high-watt flashlight. Roy was a husky man with a full head of gray hair. Randy figured his age at about seventy. “But those lights and some junk and maybe some rats and a big mess is all you're going to find.”

Randy had already declined Roy's offer to escort him. He wanted to do this alone.

The stairway was narrow and poorly lit. There was a strong smell of dust and grease and mold. Years as a cop had made Randy mostly immune to entering eerie or dangerous places, and he needed that conditioning right now. An ordinary person might have found this spooky and a bit daunting. There was no real sign of anybody's having been on these stairs in years, but then Randy remembered the prerestoration sweep ten weeks ago, the event that started all of this for him. Somebody must have checked this out then.

Randy put his left hand on a wooden banister and immediately jerked it back. It was caked with filth, dirt, crud. So he walked in the center of the stairway, doing his best to touch neither the banister on his left nor the flaking green wall on his right.

In a few moments, he was at the stairwell for Floor Two. Then he was at Three, after only one short zig and zag. And Four and Five. There was enough light so he had not yet had to turn on the flashlight or use it to fight off rats or any other creatures. He recalled what Birdie had said about the animals getting into the station. But there

had

been that sweep. Surely that would have flushed out anything live. . . .

FLOOR 6.

The wooden door with that number painted on it was dark, dirty, and cracked. It opened with a slight push.

It was pitch dark inside. Randy switched on the flashlight and found a light switch on the wall. A flicker of yellow light appeared from the ceiling. A lone bulb was hanging from a cord.

Roy had called it right. It was a mess of broken office furniture and stacks of rags and paper. Trash. The room itself was not that big: twelve feet square at most. The walls, like those on the stairway, were plaster, coated in a green paint that was falling off.

There was a large opening at the far side of the room.

Randy stepped over some paper bags stuffed with things he could not even imagine. Old rags, tickets, food wrappings, clothes? Who knew?

He was in the opening. Even without a light, which he could not find immediately, Randy knew what this room must have been: the dormitory. It was three times the size of the outer room. Again, with a dim light hanging from the ceiling and his flashlight he saw five, six, seven old metal cots stacked one on top of the other. Next to them were what remained of several blue-striped canvas mattresses that had clearly been feasted on by animals of some kind. There were large tears and bites in the fabric, tufts of white cotton protruding.

Randy didn't even try to imagine Birdie going at it with Janice or some woman traveler on one of those bedsâif he ever really did that. If any of what he said was true. . . .

Birdie. Was that his real nickname? Birdie Carlucci, as in the name of an Italian mustard. Where was the hallway, where he said he had put the record of his life at Union Station?

Randy saw an opening at the other side of the room and walkedâalmost ranâtoward it. It led into another small office, similar to the first one but full of metal filing cabinets and desks and chairs in various stages of wear and tear.

At the other end of it he saw a huge entranceway going off to the right.

He moved to it. It was a hallway.

The

hallway? He found the light switch.

Nothing happened. The one place where he really needed light and it wasn't working. No bulb, no electricity?

Damn!

Thank God for Roy's flashlight.

Moving its beam slowly from side to side, up and down, Randy saw that the hallway was long, maybe thirty feet to the end. It was at least ten feet wide. The ceiling was low, as in the other rooms, not more than twelve feet high.

The walls were that same green painted plaster. Some of the paint was flaked or missing. But . . . but! There were various initials, names, slogans, and dates scratched and cut into the paint. It was covered with graffiti, but a most special kind of graffiti. It looked like the train crews who slept up here decided to turn this hallway into an informal record of their presence.

There was

JCL-ATSF.

Somebody who worked for the Santa Fe? Yes. Underneath was 5/19/34. He scratched that into this wall on May 19, 1934? Right. Jack O.âUPâDec 17 37. A Union Pacific man. The initials and the names and the railroads and the dates covered every inch on both sides of the hallway. There were several scratched MoPac for Randy's family railroad, the Missouri Pacific. The Katy (MKT), the Burlington (CB&Q), and the others. There were dates all the way through the forties and fifties into the sixties.

Birdie, Birdie, are you really here? Where are you?

After several agonizing minutes of searching, Randy saw something that might be it. Two-thirds of the way down the hall on the right side, up near the ceiling, he saw a word that looked like

Birdie.

But the light wasn't bright enough for Randy to see it clearly from so far down.

He ran back into the first room, grabbed an old wooden office chair, and rolled it to the spot.

After determining that it would hold his weight, Randy carefully stepped up and zeroed the beam of the flashlight on the wall just below the ceiling.

BIRDIE. It had been cut into the paint in clear block letters. No question about it. B-I-R-D-I-E. There was a space and then another letter. It looked like it was an S. Yes. BIRDIE S. S for what? What was his last name: Smith? Stroud? Speakes? It could be anything. Sanders? Samuel? Hey, maybe that's it. Birdie Samuel, as in the Bible.

But that wasn't all.

Below BIRDIE S. were some dates.

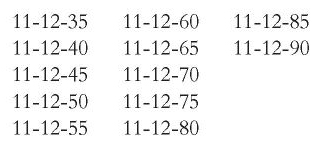

Why November 12? Randy, his mind whipping back to that day with the old man at the Kenwood residence, remembered Birdie talking about his birthday and how difficult it was to celebrate it alone. Didn't he say it was in November? Right. Maybe . . . probably . . .

Definitely.

Starting in 1935, two years after his arrival, he came up here on his birthday every five years and scratched the date on this wall under his name. That was the record of his life.

But he didn't make it up in 1995, two years ago. He most likely didn't have the strength to climb the stairs anymore. Or were the doors locked by then? Who knows why he didn't make it that one last time.

Randy reached into his suit-coat pocket. He held one of his car keys up and, underneath 11-12-90, he scratched 11-12-95.

That's what friends do.

NOTES AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The first person to assist me in a major way was Dr. Tom Lawson, the superintendent of schools in Eureka, Kansas. He gave me a copy of his Ph.D. dissertation on the state mental hospital in Osawatomie, Kansas, that he wrote while a graduate student at Kansas State University in Manhattan. Later, in person, he also shared his thoughts and cleared the way for me to visit the present-day facility at Osawatomie.

Then came Robert Unger and Jeffrey Spivak.

Bob Unger is a former national and foreign correspondent for the

Kansas City Star

and the

Chicago Tribune,

and is now professor of journalism at the University of MissouriâKansas City. Most important for me, he wrote

The Union Station Massacre: The Original Sin of J. Edgar Hoover's FBI,

the definitive work on the massacre. Published in 1997, it is the version of what happened on that June morning in 1933 that I went with. Bob met with me in Kansas City and allowed me to rustle through his massacre filesâand his mind.

Jeff Spivak is a reporter for the

Kansas City Star

and author of

Union

Station-Kansas City,

a beautifully written and illustrated book about the origin, good times/bad times, and resurrection of the station. Among other things, Jeff came with me on a tour of the building's many nooks and crannies that he arranged for me.

Another

Star

reporter, Finn Bullers, also helped me. So did Randy Proctor, Wes Cole, Kenny Servos, Doris Wesley, Fred Wiseman, Loyd Dillinger, Annette Miller, and Dr. Barbara P. Jones. I had additional assistance from the Western Historical Manuscript Collection in St. Louis and the Kansas State Historical Society in Topeka.

The last major assistâpush, reallyâcame from my editor, Bob Loomis. This book sorely needed his special brand of attention, wisdom, and hard work.

An important note on Josh's Centralia massacre recitation. His fictional recitation is based on the actual event as recounted in those five real books Will Mitchell saw on the asylum library table.

Quantrill's War

by Duane Schultz,

They Called Him Bloody Bill

by Donald R. Hale, and

Bloody Bill

Anderson

by Albert Castel and Thomas Goodrich were actually published long after it would have been possible for Josh to read and memorize words from them. I exercised poet's license to include them because the books were terrific and Josh's story needed what was in them.

There were many other books that I read in the course of my research, including

John Brown's Body

by Stephen Vincent Benét, which I quoted directly. Among the others: The Pendergast Machine by Lyle W. Dorsett,

Institutional Care of Mental Patients in the United States

by Dr. John Maurice Grimes,

Sleep Disorders Sourcebook

edited by Jenifer Swanson,

Kansas

City Southern LinesâRoute of the Southern Belle by Terry Lynch and W. C. Caileff, Jr.,

Pretty Boy

by Michael Wallis, and

Reform at Osawatomie State

HospitalâTreatment of the Mentally Ill 1866â1970

by Lowell Gish.

A point on the treatment of the patients at my fictional insane asylum: None of that was based on factual information about anything that happened at a Missouri institution. While derived from some general research, plus initial study involving the Osawatomie hospital in Kansas, the stories are complete fiction. As far as I know, for instance, no attendant at a Missouri

or

Kansas state hospital ever hit a patient in the head with a baseball bat. Some would argue that much worse things were done, but that's somebody else's story.

Finally, on the Union Station: Restored both inside and out to its original glory, the building was reopened on November 10, 1999. Inside, there are shops, restaurants, a movie theater, and a science museum, as well as a small space on the mezzanine that uses memorabilia to tell the story of the station itself.

But to me, there's much more there. I believe a caring, imaginative person can hear, smell, and feel the trains and the people who once made it a vibrant place of travel and adventureâand massacre. Some visitors, I suspect, might even come to understand why Birdie could make it his home for sixty-three years.

Read on for an excerpt from Jim Lehrer's

Tension City