Fly by Night (27 page)

“No second thoughts?” he asked.

“No.” One word, but delivered with unwavering decisiveness.

“Children?”

“No,” she said. “But someday. I am hopeful.”

“I highly recommend it.”

“It is the best one can do for the world,” she asserted, “to raise a person who will be good and kind.”

He nodded.

“So, Mr. Davis—”

He held up an admonishing finger.

“Sorry—Jammer.” She said it just like he knew she would.

Zh

for the

J

. Accent on the second syllable. Zham

mér.

He liked the way it sounded. “Enough about me,” she continued, “I would like to hear about you.”

After a pause, he said, “My wife died. It’s been almost three years.”

Her turn to say it. “I’m so sorry.”

“Diane and I were happy. Very happy. I had just retired from the Air Force and taken a job with the NTSB as an accident investigator. Things were going great. We had a terrific daughter, and our future was playing out nicely. Diane was killed in an automobile accident.”

“How awful. And your daughter?”

“She struggles with it. So do I. But time helps with things like that. Jen is in Norway right now, staying with friends and spending a semester in school. That’s the only reason I can be here now.”

“You would be a good father, I can see it.”

“I don’t feel like I am.”

“Why do you say that?”

“Right now, for example. I haven’t talked to her in over a week. My phone was my only link, and it’s out of commission.”

Antonelli reached into her purse, pulled out a heavy satellite phone, and slid it across the table. “The agency tells me I should not use it for personal calls. I ignore them.”

“Thanks.”

He picked it up and dialed Jen’s number. Six rings later he got her recording.

It’s me. You know the deal.

He waited for the tone. “Call me at this number or I’m putting you in a convent.” He gave Antonelli’s number, then hung up.

Across the table, the doctor had her knuckles to her mouth as she stifled a snicker.

The meal that came was fish—grouper, if Davis wasn’t mistaken—served with rice and some kind of local vegetable. It was damned good, one of the best meals he’d had in months.

Antonelli seemed to enjoy it as well, though at times she fell distracted. He’d noticed it before, on the long drive from Khartoum. Briefly, he thought she might be pining over her soon-to-be-ex-husband. But Davis discarded that idea. He was beginning to understand her, and suspected he knew what was really preoccupying her thoughts. Treatment plans, shipment dates, patients who needed specialists. Antonelli was the kind of doctor who took her work home. Davis recognized it because he was the same way.

To one side of the patio, the low sun was playing the hills in the distance. On the other side, the sea fell to a deep shade of purple, its choppy texture driven by a gathering breeze.

“Tell me, Jammer, how do you find an airplane that has crashed into the sea?”

Davis again looked toward the water, this time eyeing the shoreline where a small fleet of fishing boats was beached above the high-tide line.

“Actually, I need your help with that. I need to hire a guide.”

“A guide?”

“A fisherman, somebody who knows the local waters. And he has to have a boat.”

She looked at him curiously. Almost mischievously. Her mind had to be working out wild scenarios, some probably pretty amusing.

If she only knew

, he thought.

“Let me go make an inquiry,” she said. Antonelli got up and headed into the house.

By the time they finished dinner, the sun had set. They walked out to a beach that was pockmarked with footprints, the thin divide where

al-Asmat met the sea. Somewhere behind them a generator was humming, providing power for pole-mounted bulbs that gushed blotches of yellow light over the waterfront.

Davis and Antonelli found their man pulling his boat onto the beach for the night. He looked like a fisherman, a North African version of Hemingway’s old man. He might have been fifty years old, might have been a hundred. His skin was wrinkled leather, somewhere between black and brown, cured by a lifetime of saltwater and sun. The close-cropped gray hair was thin, and his black eyes were set deep behind clouded sclera, as if they had their very own measure of protection against the elements. His hands were scarred like any fisherman’s, having been pierced by hooks and fish spines, calloused from casting hand lines, hauling anchor ropes, pulling oars.

When Davis and Antonelli walked up, the man stopped his shoving and stared at them. There wasn’t any anticipation or annoyance. Maybe curiosity. Two westerners walking onto his spit of beach, clearly with something on their minds. That couldn’t happen often in al-Asmat. Probably hadn’t happened to this guy in all his years. Fifty or a hundred. Davis considered helping him pull his boat a few feet higher onto the beach, but decided against it. A guy who spent his life alone on the sea might take that the wrong way.

Antonelli looked at Davis and said, “What do you want me to ask him?”

“Just tell him I’d like to hire him.”

“He’ll think you want to go fishing.”

“Tell him I need to find something in the water.”

Antonelli said it in Arabic. The old man listened, replied with one word.

“He wants to know what you’re looking for.”

“Okay, tell him.”

Antonelli did, and the old man looked at him quizzically, probably trying to wrap his mind around the idea of using a boat to find a sunken airplane.

Davis said, “I want to hire him and his boat for a day. Ask him how much.”

She did, and got two words from the old man this time. It was probably the longest conversation he’d had in a month.

Antonelli relayed his answer. “How much do you have?”

Davis took out his wallet and turned it upside down over the weathered wooden seat in the boat. A small pile of twenties and some other odd denominations fell out. Two hundred bucks, maybe a little more.

The old man nodded, then spoke again. He was chewing something now, and Davis recognized it as khat, the herb that was wildly popular in this part of the world as a mild stimulant.

“He wants to know how you will find this airplane in the ocean,” Antonelli relayed.

Davis took out the scribbled coordinates he’d taken from Larry Green and showed them to the old man.

The old man shook his head. Spoke again.

“He says the ocean is very big, very deep. How will you

find

it?”

It was a valid question. Davis had done marine investigations before. He was practically an expert. To find submerged wreckage you wanted magnetometers and side scan sonar. You used ships that had navigation computers coupled to autopilots so that search patterns got corrected for wind and drift. Everything tight and precise. Davis had none of that. He told Antonelli his plan.

She told the old man.

He, in turn, looked quizzically at Davis. A smile creased his mahogany face and his clouded eyes sparkled. Sometimes you didn’t need to know a person’s language to understand exactly what was on their mind. Certain expressions were universal.

This I gotta see

. That’s what the old man was thinking.

Which, Davis decided, meant that his answer was yes.

It was fully dark when Antonelli and Davis made their way to the house where he’d be staying. He looked up and saw a matte-black sky that was impossibly full of stars, what you saw when you got away from the places where most people lived. There was no moon, and Davis realized he should have known this already—the precise phase,

whether it was waxing or waning. He should have worked that cycle in reverse to discover what had existed on the night of the accident. An investigator had to have all possible information, and that was a freebie. Right there in the

Farmer’s Almanac

. But Davis hadn’t, because he’d been distracted by other things. Right now he was distracted by the very attractive woman who was leading him into a sandstone building.

She stopped at the front entrance to address him. “This is the home of one of the village elders, but he is away right now. He keeps a room for guests in back. Don’t expect much, it’s rather small.”

“I’m sure it’ll be fine.”

Davis followed her inside. It really was small, just enough space for a bed and a nightstand. Right now the bed was only a naked mattress, but at the foot was a stack of sheets and a blanket—a blanket for God’s sake—resting on top of a pillow.

“You can make the bed?” she queried.

“As long as you promise not to check my square corners.”

She laughed. “There is indeed something I am beginning to like about you, Jammer.”

“My rapier wit?”

She shook her head. “More, I think, your directness. I feel as if I always know what you are thinking.”

“No. You don’t.”

Antonelli’s smile turned coy and she went to the door. “Perhaps for the better. I’ll be staying in the home to the right. It’s a good thing we stopped drinking when we did because I must wake early to open the clinic.”

Davis was feeling the wine, but not so sure they should have stopped. “I’m afraid I won’t be much help in your clinic tomorrow.”

“I understand. Pay the old man a good wage, and the money will make its way around town. Everyone will approve.”

“That’s a good way to look at it. Oh, and I was wondering—any idea where a guy could get a pair of shorts around here?”

“Shorts?”

“I may get wet tomorrow, and all I have is what’s on my back.”

Antonelli stood there thinking about shorts. He stood there thinking about her. She was positively stunning. Stunning in a pair of loose khaki work pants and a stained shirt, her long dark hair tied back in a big knot.

She said, “It might be difficult to find something in your size, but I’ll see what I can do.”

“Thanks.”

She turned to go, and called over her shoulder, “Good luck tomorrow, Jammer.”

“Thanks.” He hesitated, then said, “Hey, Contessa.”

She stopped and turned.

“Are you free for dinner tomorrow?”

She made him wait. Pretended to think about it. “Perhaps.”

And then she was gone.

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

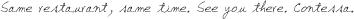

It was a chamber of commerce morning, or would have been if al-Asmat had a chamber of commerce. He found breakfast—a chunk of bread, some dates, and a small pot of coffee—on a tray near the door. There was also a pair of old shorts, folded once, and a tattered old T-shirt, XXL. On top of it all was a note written in a loopy cursive:

Davis held up the shorts. They were full of holes. Moths, bullets. No way to tell. They looked like a tight fit, but for what he had in mind that might be a good thing. He went to work on breakfast. The bread was stale, the dates fresh. He ate it all. The coffee was magnificent, not because it was any kind of fancy brew, but because he hadn’t expected any at all.

When he stepped outside the sun was already up. Seven o’clock, maybe seven thirty. He doubted precision timekeeping was a priority here. The air was still and dry, which seemed at odds with being adjacent to the sea. The temperature differential between the two should have manufactured some kind of air movement. There should have been alternating onshore and offshore breezes, cycling with day and night. There was nothing.

Davis looked for a path that led to the water, and quickly discovered that all paths led to the water. He supposed that was how it worked in a fishing village. He found the old man at his boat, coiling a line, and when he saw Davis coming he smiled a smile that put two rows of yellow, broken teeth on display.

Davis stopped right in front of him, and said, “Good morning.”

The old man nodded blankly.

It struck Davis right then how hard this was going to be. He didn’t speak a word of Arabic. His skipper probably knew “fish” and “dollar.” Maybe, “Down with America” or, “I am not a pirate.” That was the best he could hope for. So they’d have to do everything by pantomime. Pointing and nodding and waving off mistakes.

The old man finished coiling his rope. It was at least a hundred feet long, and he held up one end to show Davis the modification he’d been working on. The old guy had clearly put some thought into their mission, and Davis recognized it as just what he needed. He nodded approvingly, and thought,

Okay, maybe this little expedition will work out after all.

The boat was beached amid an outcropping of rock that was etched with tide pools. Around the freeform ponds, smooth shelves of stone were covered by gray lichens and green algae, and barnacle-like shells clung for their lives as an easy morning surf sputtered over everything again and again. Davis looked over the boat for the first time in the light of day. It was no more than twenty feet long, but the short waterline was compensated for with thick, tall gunnels. At the back, screwed onto the blunt transom, was a Yamaha outboard so small it seemed comical. Davis eyed the gas tanks. There were two, both pretty good size. Davis pointed to the gas supply and stretched out his arms to suggest measurement, adding an inquisitive face.

Do we have a lot?