Fixing the Sky

Authors: James Rodger Fleming

Table of Contents

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

COLUMBIA STUDIES IN INTERNATIONAL AND GLOBAL HISTORY

The idea of “globalization” has become a commonplace, but we lack good histories that can explain the transnational and global processes that have shaped the contemporary world. Columbia Studies in International and Global History will encourage serious scholarship on international and global history with an eye to explaining the origins of the contemporary era. Grounded in empirical research, the titles in the series will also transcend the usual area boundaries and will address questions of how history can help us understand contemporary problems, including poverty, inequality, power, political violence, and accountability beyond the nation-state.

Â

Cemil Aydin,

The Politics of Anti-Westernism in Asia:

Visions of World Order in Pan-Islamic and Pan-Asian Thought

The Politics of Anti-Westernism in Asia:

Visions of World Order in Pan-Islamic and Pan-Asian Thought

Â

Adam M. McKeown,

Melancholy Order: Asian Migration and

the Globalization of Borders

Melancholy Order: Asian Migration and

the Globalization of Borders

Â

Patrick Manning,

The African Diaspora: A History Through Culture

The African Diaspora: A History Through Culture

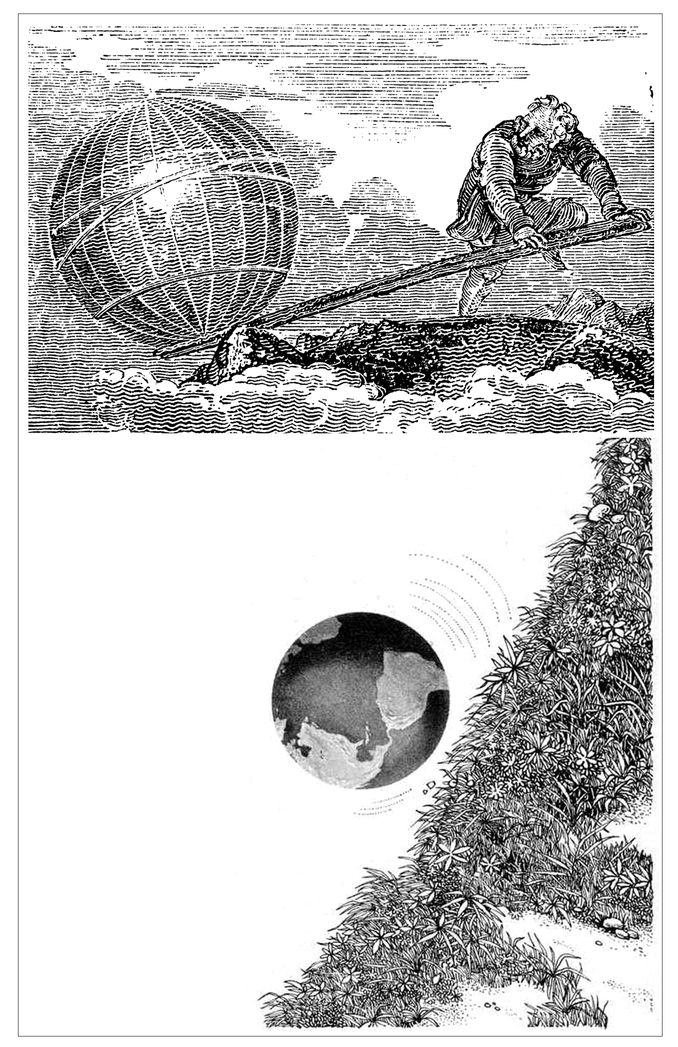

“Give me a lever long enough and a place to stand, and I will move the world” (Archimedes), but where will it roll? (

MECHANICS MAGAZINE

, 1824, AND ORIGINAL ART)

MECHANICS MAGAZINE

, 1824, AND ORIGINAL ART)

The middle course is safest and best.

âHELIOS

PREFACE

THE

possibility but not the desirability of weather and climate control entered my consciousness in the early 1970s. I was a graduate student in atmospheric science at Colorado State University and one of my air force colleagues proposed to zap clouds with laser beams to make them more energetic. I think he was wondering if a focused beam of radiation could destroy hailstones, perhaps like microwave medical treatment for kidney stones, although I suspect his patrons had other ideas. I also noted a widespread ambivalence among most of my professors toward cloud seeding, which was not part of the main curriculum. My own project involved putting cirrus clouds into a computerized tropical atmosphere and modeling their radiative effects. This was an early exercise in climate modeling. The way clouds interact with sunlight and heat radiation was very speculative then and is still an open question, even as some climate engineers propose to “manage” solar radiation.

possibility but not the desirability of weather and climate control entered my consciousness in the early 1970s. I was a graduate student in atmospheric science at Colorado State University and one of my air force colleagues proposed to zap clouds with laser beams to make them more energetic. I think he was wondering if a focused beam of radiation could destroy hailstones, perhaps like microwave medical treatment for kidney stones, although I suspect his patrons had other ideas. I also noted a widespread ambivalence among most of my professors toward cloud seeding, which was not part of the main curriculum. My own project involved putting cirrus clouds into a computerized tropical atmosphere and modeling their radiative effects. This was an early exercise in climate modeling. The way clouds interact with sunlight and heat radiation was very speculative then and is still an open question, even as some climate engineers propose to “manage” solar radiation.

Colorado State University also supported my training as a high-altitude observer, which qualified me to work with the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder in its instrumented glider project. This was an ideal job for someone who loved clouds, since we were able to slip quietly and unobtrusively

into them, spend up to several hours spiraling in their growing updrafts and collecting data, and then exit the tops of budding thunderstorms for absolutely spectacular views. This project was conducted in 1973 over the Continental Divide near Leadville, Colorado. Its poignant but unintended link to weather control came one evening, unexpectedly, when the Colorado state police visited our lodgings and informed us that someone had thrown a Molotov cocktail into the hangar and had burned up one wing of the glider. Apparently, some of the locals mistakenly thought that we were engaged in cloud seeding, or, colloquially, “stealing their sky water.”

into them, spend up to several hours spiraling in their growing updrafts and collecting data, and then exit the tops of budding thunderstorms for absolutely spectacular views. This project was conducted in 1973 over the Continental Divide near Leadville, Colorado. Its poignant but unintended link to weather control came one evening, unexpectedly, when the Colorado state police visited our lodgings and informed us that someone had thrown a Molotov cocktail into the hangar and had burned up one wing of the glider. Apparently, some of the locals mistakenly thought that we were engaged in cloud seeding, or, colloquially, “stealing their sky water.”

In my next project, at the University of Washington, I flew in a World War IIâera surplus bomber equipped with cloud physics equipment to investigate the claims of the weather modification community. The problem was, we usually flew only when the weather was bad, so we were buffeted quite frequently by Pacific storms. Early one morning, after a particularly harrowing night of flying, the airplane clipped off the top of a pine tree during our landing approach. I recall pulling a 2-inch-diameter branch out of the equipment slung below the plane and deciding, pretty much there and then, that I would be seeking other, safer modes of engagement with the atmosphere.

The history of science and technology, including its relevance to public policy, became for me that mode of engagement. I received my doctorate in history at Princeton University with a dissertation on the history of meteorology in America. Since then, I have had more than a passing interest in the history of weather and climate modification and have written several essays on the topic. I also remain deeply involved in issues involving climate change history and public policy. Today's climate engineers are championing an approach to the problem of what to do about climate change that arouses my deepest suspicions regarding technological fixes. It is a seriously flawed and speculative undertaking that typically involves impractical or even dangerous schemes to “fix the sky.” Proposals include “solar radiation management” and other forms of planetary leverage, including thermodynamically impractical schemes for large-scale carbon capture and sequestration. The proposals are typically supported by scribbling back-of-the-envelope calculations or tinkering with simple computer models that are just not good enough. It is an approach that is oblivious to the checkered history of weather and climate control.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

MOST

of the research for this book was conducted during a research leave supported by Colby College, the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the National Academy of Sciences, and the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Early versions of this work were presented at a number of venues. I extend my profound gratitude to my hosts, sponsors, listeners, and questioners.

of the research for this book was conducted during a research leave supported by Colby College, the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the National Academy of Sciences, and the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Early versions of this work were presented at a number of venues. I extend my profound gratitude to my hosts, sponsors, listeners, and questioners.

Other books

Taking Chances by Flowers, Loni

Richard III by Seward, Desmond

Unknown by Jane

Garbage Land: On the Secret Trail of Trash by Elizabeth Royte

Speak No Evil by Allison Brennan

Compelled by Shawntelle Madison

Gods of Nabban by K. V. Johansen

The Lavender Keeper by Fiona McIntosh

Embraced By Passion by Diana DeRicci

48 - Attack of the Jack-O'-Lanterns by R.L. Stine - (ebook by Undead)