Five Seasons (49 page)

Authors: A. B. Yehoshua

I

F SHE'S REALLY DYING,

he thought after dozing off again and waking up with a start, imagining for a moment that she had disappeared from the bed, at least she's doing it easily. I should only die as easily myself. It was 2

A.M.

and he felt stiff and tired. Going to the door, he looked out at the quiet ward. Only the dark-haired nurse was visible, her graceful white neck arched like a swan's above a book, a transistor radio beside her playing soft Arab music. Passing behind her as softly as a shadow, he did a sudden double take, for the book was in Arabic too. But how could I have mistaken her for a Jew? he wondered, appalled by the blindness of desire, he who had always prided himself on telling the two peoples apart. Was the other nurse also an Arab? He sought her in the hallway, failed to find her, looked in on the two old men, and noticed that an intravenous needle had slipped from its bag and was beginning to take in air. Nervously he readjusted it and returned to his mother-in-law's room, pleased with himself and swearing at the nurses, who, aware that he was up and about, soon came to ask if he meant to stay the night. “Yes,” said Molkho, “if I can.” “Then why not lie down?” they suggested again. “If she wakes, we'll wake you too.” “No, thanks,” he declined after a moment's thought. He was fine as he was, though he wouldn't object to another cup of coffee and a pillow. Intrigued by his stout, loyal figure, they brought him the coffee, a pillow, and a blanket, and he covered himself and settled back in his chair to watch the old woman fight for breath in her corner. Now and then, she opened unseeing eyes, as if deliberately snubbing him.

Suddenly he jumped to his feet, called for the nurses, and demanded that the bed be moved. “She has no air,” he told them indignantly. “Move her nearer to the window, with her face toward the sunrise. Move her!” he insisted. “The bed has wheels, move it!” They looked at each other in bewilderment, not knowing what to do, but his adamance was such that at last they gave in, first moving the chairs to make room. Drunk with fatigue he stood watching, remembering his wife with her earphones in the large hospital bed, like a radio operator going into battle. Now her mother was off to the front lines too, wheeled eastward toward a sun that soon would rise. Yes, he knew how every window in this hospital faced.

It was 3

A.M.

It's only 2

A.M.

in Europe, Molkho thought, but so what? I'm not on their time anymore.

T

HE OLD WOMAN

did not awaken when moved. He leaned over to speak to her, calling her name, praying for five minutes of consciousness. Why, she can't leave me like this, he thought, desperate for a word with her. Yet, though her eyes kept fluttering open, even resting on him with seeming approval, she refused to come to. Did she know he was there? Could she hear him? He didn't want to talk to the wall. Her thin arm helpless in its cast, like a schoolgirl's hurt at play, filled him with pity and grief. Would she be buried like that? He wet her lips with the Q-tip, watching her hand fanning in Death. “Maybe we should call a doctor,” he pleaded with the nurses, who saw no point in it. “The doctor was here in the evening and will be back at eight,” they said. “Why make him come now?” “It's an easy death,” added the brunette. “Why make it worse?” Yes, mine should be no harder, thought Molkho, sitting by the open window and wondering about the estate, of whose extent he had no idea. I'll divide it up among the children right away, he decided. I'll split it into three different savings plans for each, or maybe even six, or maybe nine to be on the safe side.

A shadow flitted across the wall. He turned to look. It was the little Russian's mother, who had apparently spent the night in her friend's room and now had come to see how she was. Startled, he half-waited for her droll bow, but she simply stood there, a golden butterball, her shy, exotic wonder all but gone. Though he quickly began to tell her about his trip, she already knew all about it, for her daughter had phoned from the Soviet Union that afternoon; indeed, there were several details that she now filled Molkho in on. “But why was the bed moved?” she asked. “Because I wanted it to be,” he answered crossly, determined to show her who was boss. Still, he told himself, I needn't wait to the bitter end. There are people who are being paid for it, and I've already been through it. Twice in one year is too much even for me.

A

T

3:30

A.M.

, not looking at all like a man just returned from abroad, he paid and tipped the driver and stepped lightly onto the sidewalk, exhausted yet floating on air. For a moment he lingered in the doorway of his house. Though his daughter had promised to leave the key in the electric box, he doubted whether she had remembered. It's been nearly a year, he thought sadly. One I was sure would be full of women, freedom, adventureâand in the end nothing came of it. Why, I didn't even make love; it's as though I were left back a grade too. And it all comes from being so passive, from expecting others to find someone for me. Lovingly, he tried thinking of his wife, but for the first time he felt that his thoughts grasped at nothing, that each time he cast their hook into the water it bobbed up light as a feather. Am I really free, then? he wondered. And if I am, what good is it? Somewhere there must be other, realer women, but for that a man has to be in love. Otherwise it's pointless, he fretted. A man has to be in love.

Â

Visit

www.hmhbooks.com

to find more books by A. B. Yehoshua.

Â

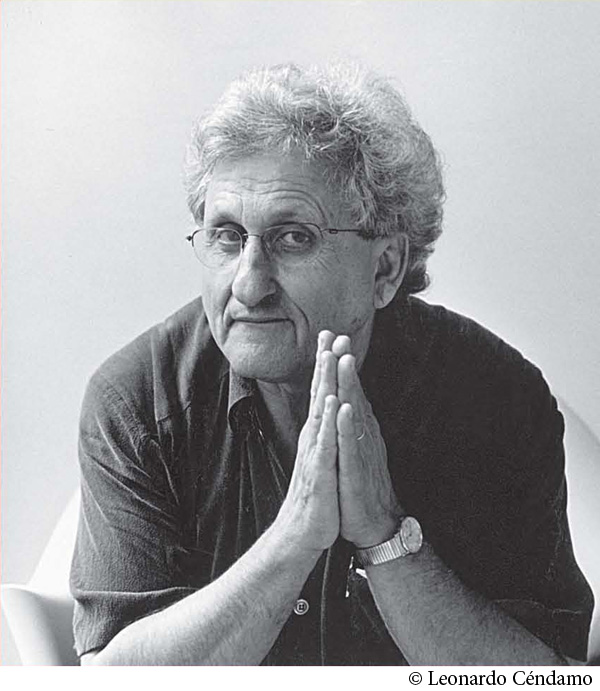

A. B. Y

EHOSHUA

is one of Israel's preeminent writers. His novels include

Journey to the End of the Millenium, The Liberated Bride,

and

A Woman in Jerusalem,

which was awarded the

Los Angeles Times

Book Prize in 2007. He lives in Haifa.