Fire and Sword (18 page)

Authors: Simon Scarrow

‘As you will.’ Castlereagh shrugged. ‘I suppose that at least warfare has the virtue of allowing a man to identify his enemies. In that respect there is much to be said for a life in uniform. See the noble features lining every table here? Not one of ’em dressed like a frog yet many of them pose an equal danger to our country. Blasted appeasers will be the ruin of us all yet!’

A sudden sharp series of knocks rang out in the chamber and Arthur turned to see the master of ceremonies striking his staff on the floor to demand silence. Quickly, the hubbub of conversation died away, cutlery was laid aside and the guests sat back in their seats, their attention drawn to the head table where the Lord Mayor had risen to begin his speech.

He began in a subdued manner, praising the sacrifice of Admiral Lord Nelson and emphasising the great sorrow of the nation, then continued in praise of the heroic efforts of the king’s soldiers and sailors to defeat France.

Arthur quickly lost interest.These were sentiments he had heard over and over again in recent days and he simply followed the cue from other guests as he nodded and applauded at the appropriate moment. His mind was consumed with the implications of his exchange with Castlereagh.

There was no doubt that Pitt was ill. But ill enough to have to surrender office? That would be a sore blow to the nation. As great, perhaps, as the death of Nelson. Few men of good sense doubted that Britain’s survival thus far in the struggle against France was down to the determination of William Pitt to see that his country maintained the struggle, whatever the cost. Lesser men would have compromised on the expense of Britain’s army and navy; Nelson’s triumph at Trafalgar was built on the sound governance of Pitt and his followers.

After William Pitt, what? Arthur pondered. There were statesmen of considerable talent in Westminster, men like Castlereagh, Canning, Grenville and Jenkinson. But each was mired in his own ambitions and there was every danger that their followers would indulge in the petty obstructionism that plagued Parliament. That could only be of benefit to Bonaparte, who was sure to rejoice if his most inveterate enemy was to quit the office of Prime Minister.The loss of Pitt would be a serious blow to the Wellesleys, who had few enough friends in Parliament. Arthur looked again at Castlereagh and wondered if the Colonial Secretary fully shared the vision of the man he had served faithfully over the years. Certainly Castlereagh wanted to prosecute the war with the same zeal, but there was a prickly pride in his nature that could easily turn him against people. A man to cultivate, Arthur concluded, but only with the utmost care and tact.

The Lord Mayor had finished his oration and the guests clapped and cheered for a moment before he raised his glass and held his hand up to silence his audience.

‘My lords, gentlemen! I give you the Prime Minister - William Pitt, the saviour of Europe!’

The chamber echoed as the guests stood, raised their glasses and loudly repeated the toast. Then the Lord Mayor took his seat and the guests followed suit, falling quiet as the Prime Minister slowly rose to make his speech of thanks to his host. For a moment he stood and silently gazed round the room, and when he spoke the tone was clear and measured.‘I return you many thanks for the honour you have done me; but Europe is not to be saved by any single man. Britain has saved herself by her exertions, and will, as I trust, save Europe by her example.’

He stood a moment longer, as if there was more that might be said, but then he bowed his head to his audience and resumed his seat.

There was a silence, before Arthur heard a voice near him whisper, ‘Is that it?’ Another voice grumbled in reply, ‘Well, really . . .’

Arthur shook his head. ‘One of the best and neatest speeches I have ever heard in my life,’ he said firmly.Across the table Castlereagh nodded solemnly. Arthur stood up and pounded his hand on the table. ‘Bravo! Bravo!’

With a smile, Castlereagh followed suit, then more men rose and soon the chamber was filled with a deafening roar. Soon only Pitt remained seated, basking in the deserved acclaim of his countrymen.

When the banquet ended, Pitt left the building first.The crowd that had cheered him into the Guildhall was still waiting outside, in the flickering glow of street lamps and the torches that some had brought with them. Another roar filled the night as he paused on the steps to give them a final wave before climbing unsteadily into his carriage and being driven away.

Arthur and Castlereagh watched him depart before the latter spoke. ‘That was well done, Sir Arthur. At the end of his little speech back there.’

‘My appreciation was sincere enough. Pitt said what needed saying without wasting one word more than was necessary.What better way to stir men’s hearts?’

Castlereagh nodded. ‘Anyway,Wellesley, I bid you good night. I trust you will serve your country well in Germany. I shall be watching your career with interest.’

A few days later the letter came from Lord Castlereagh’s office appointing Arthur to the command of an infantry brigade billeted at Deal. At once he was thrown into the business of preparing himself for the post. Uniforms and a wardrobe fit for a winter campaign had to be bought and packed, bookshops scoured for reference works and maps on the regions through which the British army might be expected to march. His mother watched proceedings with a critical eye and made occasional sharp comments about children who left her almost as soon as they had bothered to return home.

Amongst his other preparations Arthur hurriedly composed letters to friends and acquaintances informing them of the forthcoming campaign. He wrote a brief note to Kitty telling her of his return and imminent departure. He carefully expressed his wish to see her again as soon as he was home again. To Richard he wrote of the political situation, and the encouraging views he had heard from Pitt and even Castlereagh with respect to Richard’s treatment once he arrived back in Britain. Before leaving London he paid a final visit to the Sparrows’ house, hoping to hear more of Kitty.

Mrs Sparrow received his news with a sad expression. ‘Well, I suppose a soldier must do his duty.’

‘Yes.’ Arthur nodded. ‘There is always duty, and will be until the war is ended for good.’

‘And then?’

‘Then I can enjoy the fruits of peace with a full heart, lay down my duties and resume my life.’ Arthur cleared his throat. ‘I wondered if you had heard anything from Kitty?’

Mrs Sparrow nodded. ‘She told me she had a letter from you. She said it was a bit stiff and stilted, but all the same it has raised her spirits, although it has given her no little cause for concern.’

‘Concern?’ Arthur frowned. ‘Why?’

‘Because she is unsure how to respond to it. Suffice to say that you have reawoken her old affection for you. The difficulty is that she is nervous that the Kitty you express feelings towards is no more than a memory, a person gone from your life these ten years.’

‘Ten years,’Arthur mused,‘in which she has always been in my heart.’

‘And you in hers.’

‘Not always, it would seem,’ Arthur replied sharply, still feeling a cold jealous rage at Galbraith Lowry Cole for all the time he had shared with Kitty while Arthur was in India. Then, with a deep sigh, he fought the unworthy impulse.

‘What did you expect,Arthur? Besides, it could be worse.What if she had found someone whom Tom Pakenham would have allowed her to marry? What then?’

‘Then . . . I think I would rather have died,’Arthur replied with quiet sincerity. ‘But at least she is uncommitted for the present.’

Mrs Sparrow shook her head.‘She is committed rightly enough, but only to you, Arthur. The poor girl is in an agony of indecision. She wants to see you, but fears it too much at the same time.’

‘Then I must put an end to her indecision,’ Arthur resolved. ‘Once and for all.’

‘How?’

‘I will write to her again. This time I shall make her an offer. I shall honour the letter I left her with ten years ago. If you speak accurately of her feelings, then surely she will accept?’ Arthur looked at Mrs Sparrow almost pleadingly, and she smiled.

‘Surely!’

For the rest of November Arthur and his men waited to board their ships, but the winter gales were against them and the British army could only stand helpless as their allies marched against Napoleon on the continent. Rumours and fragments of news seeped across the Channel, some claiming another French victory, others that the Russians had joined their Austrian allies and were closing the trap on Bonaparte.

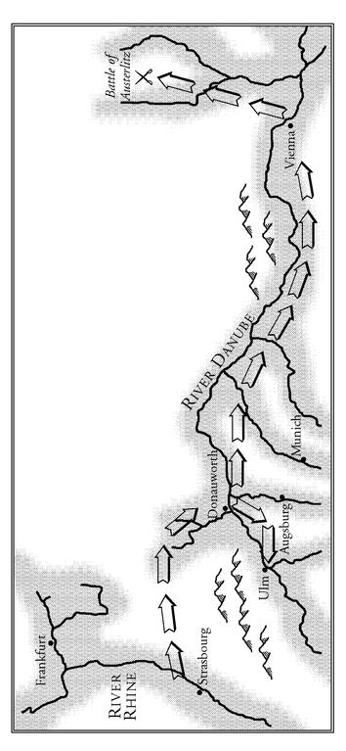

At the end of November the wind changed at last and the British soldiers embarked on their transport for the rough crossing of the North Sea.The convoys of troopships and their Royal Navy escorts beat their way over the slate-grey water towards the coastline of northern Europe, where they entered the River Weser. There they anchored and prepared to land, making ready to advance towards the Danube.

As light faded on the afternoon of their arrival, Arthur stood on the deck of a frigate, wrapped in his coat as he surveyed the bleak winter landscape on either bank. A light shower of snow had fallen earlier and coated the roofs of the nearest hamlet in a pale sheen.The sky was dark and grey and threatened yet more snow.

Behind Arthur the lieutenant of the watch was pacing up and down as his sailors completed the furling of the sails and descended below decks for their evening meal. Arthur took one last glance at the sky and was about to head back to his cabin when there was a shout from aloft.

‘Deck there! Boat approaching!’

Arthur paused, and then turned to scan the river behind him in the gathering gloom.

Sure enough, a ship’s gig had rounded the nearest bend and was making straight for the frigate, which was anchored at the head of the line of transports.An army officer was seated in the stern and as the boat drew up to the side of the frigate he jumped up, and nearly tumbled over the side in his lubberly eagerness to clamber up on to the deck. A moment later, with the helping hands of the sailors in the gig, the officer, a young major on the headquarters staff, scrambled on to the deck and addressed the nearest midshipman.

‘You! Where can I find Major-General Wellesley?’

Arthur strode towards him. ‘Here!’

The officer, panting, hurried up to Arthur and fumbled inside the breast of his coat for a despatch. ‘From the flagship, sir.We got the news just over an hour ago.’

‘What news?’

‘There’s been a great battle, sir.’ The man’s eyes were wide with excitement. ‘Not far from Vienna. At a place called Austerlitz.’

00

Chapter 13

Napoleon

As soon as the arrangements had been made for the paroling of some of the prisoners captured at Ulm and sending the rest into holding camps in Bavaria and France, the Grand Army wheeled about and marched against the Russian army led by Kutusov. For the remainder of October, and into the early days of November the soldiers trudged towards Vienna, driving the enemy before them.The weather continued to worsen as autumn began to give way to winter.

On some days, there were bright spells when brilliant white puffy clouds billowed serenely across a clear sky.Then there were times when thick banks of rain and mist blotted out the sun and icy squalls lashed down, soaking the men through to the skin and turning the routes along which they marched into glutinous slippery bogs. At night the temperature dropped swiftly and the men huddled around their campfires, trying to dry their clothes and get some warmth into their shivering frames as they supped on whatever food they had managed to forage during the afternoon. The lucky ones, mostly veterans who had long since learned the knack of finding good shelter, slept under cover, while the rest made themselves as comfortable as they could in the open. There were frequent frosts in the morning when the men woke to find their belongings covered in a gleaming patina of tiny ice crystals that gleamed pale blue in the hour before dawn. After a quick meal the men formed up, stamping their feet to keep warm, and then, when the order was given, they advanced towards the enemy again.

Other books

February (Calendar Girl #2) by Audrey Carlan

Shameful Reckonings by S. J. Lewis

Listed: Volume IV by Noelle Adams

Jasmine Nights by Julia Gregson

Aunt Sandy's Medical Marijuana Cookbook by Sandy Moriarty

By His Rules by Rock, J. A.

The Willard by LeAnne Burnett Morse

What is the Matter with Mary Jane? by Wendy Harmer

Whiskey Kisses by Addison Moore