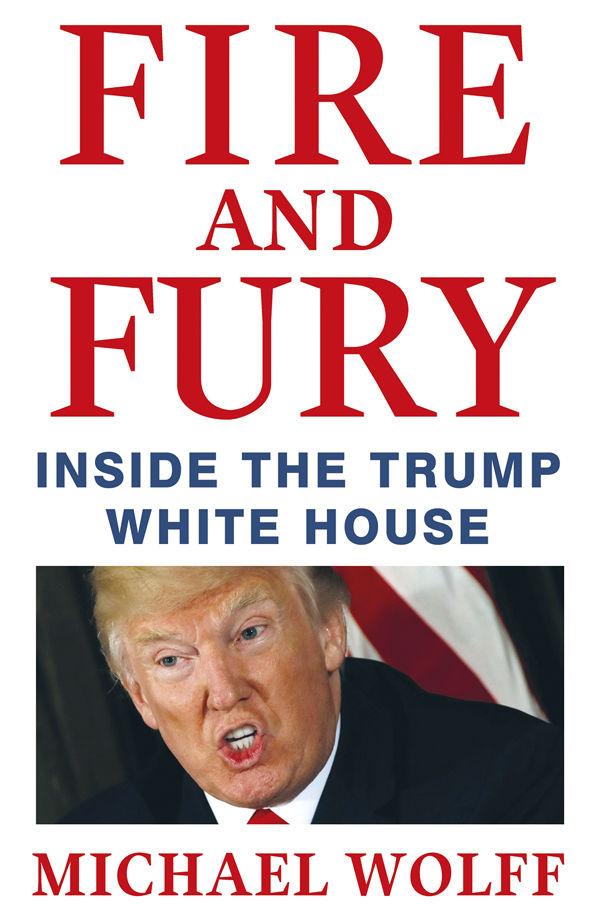

Fire and Fury

Authors: Michael Wolff

ALSO BY MICHAEL WOLFF

Television Is the New Television:

The Unexpected Triumph of Old Media in the Digital Age

The Man Who Owns the News:

Inside the Secret World of Rupert Murdoch

Autumn of the Moguls:

My Misadventures with the Titans, Poseurs, and Money Guys Who Mastered and Messed Up Big Media

Burn Rate:

How I Survived the Gold Rush Years on the Internet

Where We Stand

White Kids

LITTLE, BROWN

First published in the United States in 2018 by Henry Holt and Company

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by Little, Brown

Copyright © 2018 by Michael Wolff

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Designed by Meryl Sussman Levavi

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-4087-1138-5

Little, Brown

An imprint of

Little, Brown Book Group

Carmelite House

50 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DZ

An Hachette UK Company

For Victoria and Louise, mother and daughter

AUTHOR’S NOTE

The reason to write this book could not be more obvious. With the inauguration of Donald Trump on January 20, 2017, the United States entered the eye of the most extraordinary political storm since at least Watergate. As the day approached, I set out to tell this story in as contemporaneous a fashion as possible, and to try to see life in the Trump White House through the eyes of the people closest to it.

This was originally conceived as an account of the Trump administration’s first hundred days, that most traditional marker of a presidency. But events barreled on without natural pause for more than two hundred days, the curtain coming down on the first act of Trump’s presidency only with the appointment of retired general John Kelly as the chief of staff in late July and the exit of chief strategist Stephen K. Bannon three weeks later.

The events I’ve described in these pages are based on conversations that took place over a period of eighteen months with the president, with most members of his senior staff—some of whom talked to me dozens of times—and with many people who they in turn spoke to. The first interview occurred well before I could have imagined a Trump White House, much less a book about it, in late May 2016 at Trump’s home in Beverly Hills—the then candidate polishing off a pint of Häagen-Dazs vanilla as he happily and idly opined about a range of topics while his aides, Hope

Hicks, Corey Lewandowski, and Jared Kushner, went in and out of the room. Conversations with members of the campaign’s team continued through the Republican Convention in Cleveland, when it was still hardly possible to conceive of Trump’s election. They moved on to Trump Tower with a voluble Steve Bannon—before the election, when he still seemed like an entertaining oddity, and later, after the election, when he seemed like a miracle worker.

Shortly after January 20, I took up something like a semipermanent seat on a couch in the West Wing. Since then I have conducted more than two hundred interviews.

While the Trump administration has made hostility to the press a virtual policy, it has also been more open to the media than any White House in recent memory. In the beginning, I sought a level of formal access to this White House, something of a fly-on-the-wall status. The president himself encouraged this idea. But, given the many fiefdoms in the Trump White House that came into open conflict from the first days of the administration, there seemed no one person able to make this happen. Equally, there was no one to say “Go away.” Hence I became more a constant interloper than an invited guest—something quite close to an actual fly on the wall—having accepted no rules nor having made any promises about what I might or might not write.

Many of the accounts of what has happened in the Trump White House are in conflict with one another; many, in Trumpian fashion, are baldly untrue. Those conflicts, and that looseness with the truth, if not with reality itself, are an elemental thread of the book. Sometimes I have let the players offer their versions, in turn allowing the reader to judge them. In other instances I have, through a consistency in accounts and through sources I have come to trust, settled on a version of events I believe to be true.

Some of my sources spoke to me on so-called deep background, a convention of contemporary political books that allows for a disembodied description of events provided by an unnamed witness to them. I have also relied on off-the-record interviews, allowing a source to provide a direct quote with the understanding that it was not for attribution. Other sources spoke to me with the understanding that the material in

the interviews would not become public until the book came out. Finally, some sources spoke forthrightly on the record.

At the same time, it is worth noting some of the journalistic conundrums that I faced when dealing with the Trump administration, many of them the result of the White House’s absence of official procedures and the lack of experience of its principals. These challenges have included dealing with off-the-record or deep-background material that was later casually put on the record; sources who provided accounts in confidence and subsequently shared them widely, as though liberated by their first utterances; a frequent inattention to setting any parameters on the use of a conversation; a source’s views being so well known and widely shared that it would be risible not to credit them; and the almost samizdat sharing, or gobsmacked retelling, of otherwise private and deep-background conversations. And everywhere in this story is the president’s own constant, tireless, and uncontrolled voice, public and private, shared by others on a daily basis, sometimes virtually as he utters it.

For whatever reason, almost everyone I contacted—senior members of the White House staff as well as dedicated observers of it—shared large amounts of time with me and went to great effort to help shed light on the unique nature of life inside the Trump White House. In the end, what I witnessed, and what this book is about, is a group of people who have struggled, each in their own way, to come to terms with the meaning of working for Donald Trump.

I owe them an enormous debt.

AILES AND BANNON

T

he evening began at six-thirty, but Steve Bannon, suddenly among the world’s most powerful men and now less and less mindful of time constraints, was late.

Bannon had promised to come to this small dinner arranged by mutual friends in a Greenwich Village town house to see Roger Ailes, the former head of Fox News and the most significant figure in right-wing media and Bannon’s sometime mentor. The next day, January 4, 2017—little more than two weeks before the inauguration of his friend Donald Trump as the forty-fifth president—Ailes would be heading to Palm Beach, into a forced, but he hoped temporary, retirement.

Snow was threatening, and for a while the dinner appeared doubtful. The seventy-six-year-old Ailes, with a long history of leg and hip problems, was barely walking, and, coming in to Manhattan with his wife Beth from their upstate home on the Hudson, was wary of slippery streets. But Ailes was eager to see Bannon. Bannon’s aide, Alexandra Preate, kept texting steady updates on Bannon’s progress extracting himself from Trump Tower.

As the small group waited for Bannon, it was Ailes’s evening. Quite as dumbfounded by his old friend Donald Trump’s victory as most everyone else, Ailes provided the gathering with something of a mini-seminar on the randomness and absurdities of politics. Before launching Fox

News in 1996, Ailes had been, for thirty years, among the leading political operatives in the Republican Party. As surprised as he was by this election, he could yet make a case for a straight line from Nixon to Trump. He just wasn’t sure, he said, that Trump himself, at various times a Republican, Independent, and Democrat, could make the case. Still, he thought he knew Trump as well as anyone did and was eager to offer his help. He was also eager to get back into the right-wing media game, and he energetically described some of the possibilities for coming up with the billion or so dollars he thought he would need for a new cable network.

Both men, Ailes and Bannon, fancied themselves particular students of history, both autodidacts partial to universal field theories. They saw this in a charismatic sense—they had a personal relationship with history, as well as with Donald Trump.

Now, however reluctantly, Ailes understood that, at least for the moment, he was passing the right-wing torch to Bannon. It was a torch that burned bright with ironies. Ailes’s Fox News, with its $1.5 billion in annual profits, had dominated Republican politics for two decades. Now Bannon’s Breitbart News, with its mere $1.5 million in annual profits, was claiming that role. For thirty years, Ailes—until recently the single most powerful person in conservative politics—had humored and tolerated Donald Trump, but in the end Bannon and Breitbart had elected him.

Six months before, when a Trump victory still seemed out of the realm of the possible, Ailes, accused of sexual harassment, was cashiered from Fox News in a move engineered by the liberal sons of conservative eighty-five-year-old Rupert Murdoch, the controlling shareholder of Fox News and the most powerful media owner of the age. Ailes’s downfall was cause for much liberal celebration: the greatest conservative bugbear in modern politics had been felled by the new social norm. Then Trump, hardly three months later, accused of vastly more louche and abusive behavior, was elected president.

* * *

Ailes enjoyed many things about Trump: his salesmanship, his showmanship, his gossip. He admired Trump’s sixth sense for the public marketplace—or at least the relentlessness and indefatigability of his

ceaseless attempts to win it over. He liked Trump’s game. He liked Trump’s impact and his shamelessness. “He just keeps going,” Ailes had marveled to a friend after the first debate with Hillary Clinton. “You hit Donald along the head, and he keeps going. He doesn’t even know he’s been hit.”

But Ailes was convinced that Trump had no political beliefs or backbone. The fact that Trump had become the ultimate avatar of Fox’s angry common man was another sign that we were living in an upside-down world. The joke was on somebody—and Ailes thought it might be on him.