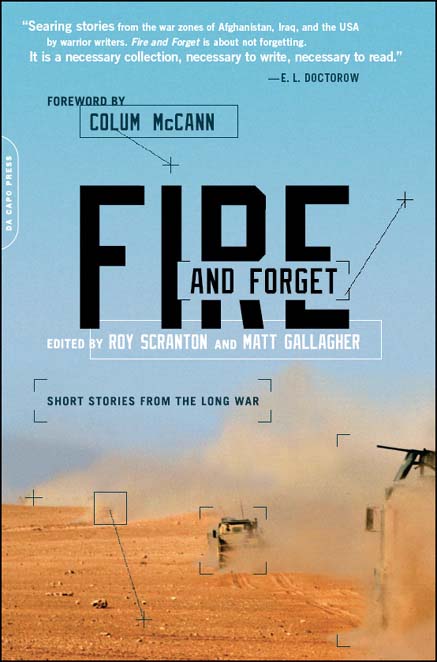

Fire and Forget

Authors: Matt Gallagher

FIRE

AND

FORGET

FIRE

AND

FORGET

SHORT STORIES

FROM THE LONG WAR

EDITED BY

ROY SCRANTON

AND

MATT GALLAGHER

DA CAPO PRESS

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

FOREWORD BY

COLUM MCCANN

Copyright © 2013 by Da Capo Press.

Foreword copyright © 2013 by Column McCann.

Preface copyright © 2013 by Roy Scranton.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic,

mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior written permission of the publisher.

For information, address Da Capo Press, 44 Farnsworth, 3rd floor, Boston, MA 02210.

“Big Two-Hearted Hunting Creek” first appeared in

The Southern Review

45:3 (Summer 2009);

“Redeployment” first appeared in

Granta

116 (September 2011);

“Tips for a Smooth Transition” first appeared in

Salamander

(June 2012).

Editorial production by Lori Hobkirk at the Book Factory.

Book design by Cynthia Young at Sagecraft.

Set in 11.5 point Adobe Garamond Pro

A CIP catalog record for this book is

available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN: 978-0-306-82117-6 (e-book)

Published by Da Capo Press

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

Da Capo Press books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail

[email protected]

.

10Â Â 9Â Â 8Â Â 7Â Â 6Â Â 5Â Â 4Â Â 3Â Â 2Â Â 1

Foreword: Eclipsing War, by Colum McCann

Â

Â

1Â Â Â Smile, There Are IEDs Everywhere

| Jacob Siegel

Â

2Â Â Â Tips for a Smooth Transition

| Siobhan Fallon

Â

3Â Â Â Redeployment

| Phil Klay

Â

4Â Â Â The Wave That Takes Them Under

| Brian Turner

Â

5Â Â Â The Train

| Mariette Kalinowski

Â

7Â Â Â Play the Game

| Colby Buzzell

Â

8Â Â Â Television

| Roman Skaskiw

Â

9Â Â Â New Me

| Andrew Slater

10Â Â Â Poughkeepsie

| Perry O'Brien

11Â Â Â When Engaging Targets, Remember

| Gavin Ford Kovite

12Â Â Â Big Two-Hearted Hunting Creek

| Brian Van Reet

13Â Â Â Roll Call

| David Abrams

14Â Â Â And Bugs Don't Bleed

| Matt Gallagher

15Â Â Â Red Steel India

| Roy Scranton

Â

Eclipsing War

Colum McCann

All stories are war stories somehow. Every one of us has stepped from one war or another. Our grandfathers were there when the stench of Dresden hung over the world, and our fathers were there when Vietnam sent its children running napalmed down the dirt road. Our grandmothers were there when Belfast fell into rubble, and our mothers were there when Cambodia became a crucible of bones. Our sisters in South Africa, our brothers in Gaza. And, God forbid, our sons and daughters will have stories to tell too. We are scripted by war.

It is the job of literature to confront the terrible truths of what war has done and continues to do to us. It is also the job of literature to make sense of whatever small beauty we can rescue from the maelstrom.

Writing fiction is necessarily a political act. And writing war fiction, during a time of war, by veterans of the conflicts we are still fighting, is a fervent, and occasionally anguished, political act.

The stories of the wars that defined the first decade of the twenty-first century are only just beginning to be told. Television programs, newspaper columns, Internet blogs. We've even had a couple of average Hollywood movies, but we don't yet have all the stories, the kind of reinterpretive truth-telling that fiction and poetry can offer.

It is the dream of writers to get at the pulse of the moment. To inhabit the depth of the wound. E. L. Doctorow gave us the Civil War in

The March

. Jennifer Johnston gave us the First World War in

How Many Miles to Babylon?

Tim O'Brien gave us Vietnam in

The Things They Carried

. Norman Mailer gave us World War II in

The Naked and the Dead

. Edna O'Brien gave us Ireland in

House of Splendid Isolation

. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie gave us the Biafran War in

Half of a Yellow Sun

.

We are drawn to war because we are, in the words of William Faulkner, drawn to “the human heart in conflict with itself.” We all know that happiness throws white ink against a white page. What we need is darkness for the meaning to come clear. We discover ourselves through our battlesâour awful revelations, our highest dreams, our basest instincts are all on display.

For the fifteen writers of this anthology, the war is not simply a sequence of unpleasant images or unremitting woes. By entering into the lives of their characters, they allow the reader access to the viscerally intense but morally ambiguous realities of war. The consequences echo back to the American culture that our soldiers have emerged from. This, in turn, kicks forward into a global culture. Each bullet is inevitably followed by another. One story becomes all stories. And we have to keep on telling them. It is our duty to continue spinning the kaleidoscope.

I have a special and abiding relationship to this anthology. Along with several other writers and teachers, I was also honored to be a guest at New York University. It was ambassador Jean Kennedy Smithâone of the great humanitarians of our timeâ

who called me up and asked me if I would attend. It was my privilegeâand indeed my education.

The group was intended to be non-ideological, focused purely on the craft of writing and free to all veterans. Six of the writers in this anthology (Matt Gallagher, Gavin Kovite, Phil Klay, Perry O'Brien, Roy Scranton, and Jake Siegel) met at the program where the veterans discussed fiction, read each other's work, and had an opportunity to share their ideas about representations of the wars. The group began reaching out beyond New York, and connections were established between veterans across the country committed to writing serious, literary fiction.

The war went literary. And the literature broke our tired hearts. The fact of the matter is that we get our voices from the voices of others. Most prominently we get our voices from those who are on the front line. This anthology is a testament to that. It is something to be taught down through the years. There are stories by infantrymen, staff officers, public affairs Marines, a military lawyer, an artilleryman, a military spouse, a medic, an Army Ranger, and a Green Beret. This is not simply the first fiction anthology by veterans of those wars, it is also a harbinger of the novels and short story collections we will be seeing in the future, as those who served continue to try to make sense of our wars for us in the most rigorous way possible, through fiction.

As a teacher at Hunter College, New York, I am always looking for new writers who are prepared to wake me up from my stupor. I will never forget the day, four years ago now, when I opened up the file by a young Phil Klay. The first line stunned me. “We shot dogs.” I knew from that very moment that I was in the hands of a masterful young writer. The story, published here as “Redeployment,” puts you in the boots of a Marine returning home but still besieged by memories of the Second Battle of Fallujah. It unflinchingly explores the effects of battle and the

bizarre challenges of returning home. The truth of the matter is that you can't go back to the country that doesn't exist anymore.

More recently I stumbled upon the fiction of Mariette Kalinowski. She is the sort of writer who is prepared to step off cliffs and develop her wings on the way down. In this anthology, her story, “The Train,” puts us in the head of a female veteran who obsessively rides the New York City subway back and forth, back and forth. Her combat trauma forces her underground, farther from her time in Iraq and from the friend that she lost there.

Here it is, the cyclorama of war.

In Roman Skaskiw's “Television,” a lieutenant handles the aftermath of an engagement where, “No one was hurt, just a local kid they shot,” and has to deal with the murky realities of a war where enemies are hard to spot, and some soldiers are overeager to pull the trigger.

In “Roll Call,” by twenty-year career Army non-commissioned officer David Abrams, a memorial ceremony held in the country becomes an occasion to reflect on all the dead, and on the individual soldier's chances of survival.

Renowned poet Brian Turner, in “The Wave That Takes Us Under,” turns a lost patrol into a meditation on death and the dying.

“For us, there had been no fields of battle to frame the enemy,” writes Jake Siegel. “Our shocks of battle came on the road, brief, dark, and anonymous.” But in Siegel's story the terrors of the road seem almost simple when compared with the narrator's difficulties in truly coming home from his war. Unable to talk about his time in Iraq, he opens up only when two buddies from overseas meet him for a night of drinking in New York. What he finds, though, is that even that camaraderie he cherished is nothing but a memory.

Other authors give us different homecomings, intersecting the memories of war with an American culture far removed from the

worlds of poverty, violence, and pain the veterans have experienced. Siobhan Fallon, author of the short story collection

You Know When the Men Are Gone,

tells the other side of the story, from the perspective of an army wife. Though her character's guidebook offers helpful suggestions, (“Typically, a âhoneymoon' period follows in which couples reunite physically, but not necessarily emotionally. . . . Be patient and communicate”), she finds the actual experience of putting that advice into action challenging and terrifying.

In this anthology, the authors deal not just with the raw reportage of war, but with its aftermath too.

Brian Van Reet, awarded the Bronze Star for valor, writes of the soldiers receiving medical care for horrific burns. These men, some without faces or, in one case, without genitals, go on a fishing trip that is meant to boost their morale but which turns into a potentially violent encounter with a pair of civilian girls. Colby Buzzell's “Play the Game” details the limited options for an infantry veteran who doesn't want to stay in the Army but can't find a job in an America wracked by recession. Former Green Beret Andrew Slater, in “New Me,” puts the reader into the mind of a soldier with a traumatic brain injury, whose past enters his dreams and overshadows his new life. Matt Gallagher, author of the memoir

Kaboom

, dramatizes the strange difficulties in adjusting to life back home with “And Bugs Don't Bleed,” a story where a soldier's increasing alienation ends in a small act of perversely cruel violence that seems directed at himself as much as it is against the complacent and happy civilian world.