Finding Zero (2 page)

Authors: Amir D. Aczel

At school I was often bored. I enjoyed immensely the experiential learning I could pursue aboard ship: finding out firsthand how the world works, even as seen from the still-developing vantage point of a child. I liked being taught about life by my parents and by ship's stewards, and mostly by the dedicated, highly attentive, and instructive Laci. At school, on the other hand, everything

seemed rote, divorced from reality, and lacking excitement. There, I simply coasted, doing the minimum and counting the days till we could join my father on the ship. I couldn't wait to be back aboard with my friend and mentor; and my child's intuition told me that he knew much more than he was teaching me.

I had developed an obsession with finding the origin of the ornate numerals I had seen on the gaming table at the casino. I wanted to know where the numerals we use everywhere originally came from, and I was looking forward to Laci telling me more about themâand showing me new things about numbers through our travel experiences. I was barely beginning to understand that there were two related concepts here: numerals and numbers. Numbers were abstract entities. And I felt that there was much more here to be discovered, even if the true depth of the concept of

number

was still beyond my abilities to fully understand. I was mature enough, however, to want to learn how the signs that stand for numbers, the ten numerals we use today, came into being.

The next interesting sailing

we did with the ship was something special. Instead of the usual pleasure cruises to party islands or opulent casinos (this was before gambling aboard ships had become the norm), the shipping company sent its flagship, captained by my father, on a historical-educational cruise (this, too, was a noveltyâit happened before mass “cultural tourism” was born). We sailed first to Piraeus, the port of Athens, and the passengers had an expertly guided tour of the Acropolis and lectures on the birth of Greek democracy, architecture, sculpture, and mathematics.

My father loved the good lifeâand as ship's captain, he lived it. In every port, the local shipping agent invited him to dinner at the most expensive or most unusual restaurant in town. In Piraeus, the ship's agent was Mr. Papaioanis, a jovial, paunchy Greek originally from the island of Patmos. He invited us all to dinner at a beach restaurant called

To Poseidoneion

(Poseidon's), on one of the backstreets facing the sea. When I think back to that outing so many years ago, I can still smell the fresh shrimp grilling on an open fire and feel the gentle sea wind brush my face; when I close my eyes, I can still see the lights of distant fishing boats gently rolling in the water and hear the waves crashing on the sand. It was a wonderful evening and I hoped it would never end. It was my introduction to Greece and its pleasures. After this wonderful meal, we all took a long walk along the edge of the water, eventually winding our way all the way back to the Port of Piraeus and to our ship, docked by a central pier flanked by two ferries.

The next morning, Laci woke me up early. “When your sister and mother go shopping today, let me take you to see the ancient Greek numbers,” he said. “Great!” I answered as I jumped out of bed and started to get dressed. This was going to be an exciting day. I went to my father's large cabin to wait for Laci. He had already prepared my breakfast, and I enjoyed the hot chocolate and the freshly baked, still-steaming croissant made in the ship's ovens.

My father was up on the bridge, and while I was finishing my breakfastâmy mother and sister were still asleepâhe came down and into the cabin. “You're up early,” he said. “Yes,” I answered excitedly, “Laci is taking me to Athens to look at ancient Greek numbers!” My father nodded. I wasn't sure that he understoodâor

appreciatedâhow important to me my relationship with Laci was: that I would even give up time with my family to go look at some numbers with him.

Laci came, and we went down the gangway to the pier and into a cab that was waiting for us. We drove through the heavy morning traffic of greater Athens, climbing up the densely populated hills between Piraeus and the Greek capital. The pollution was heavyâthe Athens area, like Los Angeles, suffers from a thermal inversion pattern that traps gasses and particlesâand the bad air made me cough frequently. In about an hour we came to the center of Athens and the cab dropped us off at the Plaka, the city square below the acropolis, full of shops and boutiques and cafes. From there, we climbed up the steep path of the acropolis hill to the Parthenon, the fifth-century BCE temple to the Greek goddess Athena.

We walked slowly up the white stone path. The air was clear and crisp here, and crocuses were blooming; I could smell the fresh scent of the pine trees around us. At the very top, we paid the entrance fee and went into the ruins of the ancient acropolis. We then slowly climbed up the stone stairs to the famous Parthenon. I stopped from time to time to catch my breath and to admire the incredible view of the temple from below as I climbed toward it.

“Beautiful, isn't it?” asked Laci.

“Yes,” I said. “It's a very pretty building with these columns.”

“These are made of marble,” he said. “But you know why you find it so beautiful?” I said I didn't know. “It's the proportion,” he said. “The Parthenon follows the ancient Greek proportion called the golden ratio. The ratio of its length to its height is about 1.618,

a number that seems to characterize many things we consider beautifulâand it also appears in nature.” I was fascinated. He explained that the golden ratio came from a mathematical series of numbers called the Fibonacci sequence, and he showed me how it is obtained, each number being the sum of the two previous ones: 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, and so on. If you divide a number by its predecessor, you get something approximating the golden ratio of 1.618. (For example, the sequence continues with 55 and 89. The ratio of 89 to 55 is 1.61818 . . .) I found this idea enthralling.

We went into the Parthenon and saw some statues, beautiful likenesses of the goddess Athena still with traces of ancient red and gold paint on her face. Laci bent down and pointed to the pedestal of one of the statues and showed me letters carved in the marble. “Look,” he said. “This is what I wanted you to see.” I saw a letter I did not recognizeâit was Greek. “Greek letters were not only used for writing, but also for numbers,” Laci said. The letter he was pointing to, he explained, was the Greek delta. It stood for the number four. “This was the fourth statue out of the assemblage that once stood here,” he said.

After spending an hour admiring this monument of ancient Greek civilization, we left the temple and began to descend slowly. We stopped to sit down on a flat marble slab that was once part of this columned edifice. From here we could admire the Parthenon. It was hot, and we drank water from plastic bottles Laci had bought. After a few moments, he took out a notebook and showed me how the Greeks used letters as their numerals, and how their arithmetic, using only letters and no zero, worked. Here is what he wrote:

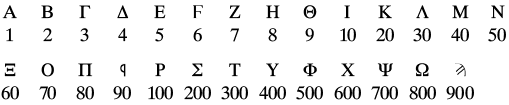

The Greek letters used as numbers (including the archaic letters digamma, koppa, and sampi).

The Greek alphabet of that time, the fifth century BCEâthe height of classical Greeceâincluded letters that had been extinct since antiquity:

digamma

( ) for 6;

) for 6;

koppa

( ) for 90; and

) for 90; and

sampi

( ) for 900. So by the fifth century BCE the Greeks had revived letters in an alphabet they no longer used for writing, just so they would have enough symbols for numbers.

) for 900. So by the fifth century BCE the Greeks had revived letters in an alphabet they no longer used for writing, just so they would have enough symbols for numbers.

Laci pointed out that the custom of using letters for numbers was rooted in Phoenicia, from which the Hebrew alphabet hails as well. Some Orthodox Jews to this day, he explained, have watches with faces displaying Hebrew letters for the numbers from 1 to 12.

We then went to the museum of Athens, one of the greatest archaeological museums in the world. Among beautiful statues of gods and goddesses I saw several stone inscriptions with numbers represented as letters.

On the way back to the ship, Laci asked the driver to stop in an alley in Piraeus and had me wait in the cab while he went into what looked like a store selling discount electronics. When he came back, he had a small package in his hand. “It's just a small transistor radio,” he said to me. These were the new popular products of the time, the early 1960s, and people were going crazy over

them. You would see a person walking down the street listening to a transistor radio as often as today you might see someone talking on a cellular phone. “Just a present for someone,” he said. I thought nothing more about it at the time.

After leaving Piraeus that evening, the

Theodor Herzl

sailed to Naples, and the passengers spent the day visiting nearby Pompeii. Next, there was a stop at Civitavecchia, the modern-day port of Rome (in antiquity Rome's port was Ostia). The passengers had a tour of the city, with an in-depth study of Rome and the history of its empire. For a boy interested in the history of numbers, this was a cruise to remember.

In Pompeii, Laci and I traced the Roman numeralsâall Latin lettersâthat were used for house numbers in this ancient town. Its ruins were in a remarkable state of preservation as they had been covered by volcanic ash for almost two millennia after the catastrophic eruption of Vesuvius in 79 CE. At its museum we saw more numbers written using letters, and it was fun to read them and even try basic arithmetic.

Rome was a feast for a budding number-hunter. Roman numerals were everywhere. Most interesting were the milestones the Romans had placed along their straight-as-a-ruler roads, and I slowly became adept at reading the distances on these ancient markers, which I saw in museums and on the most famous of Roman roads, the Via Appia Antica.

Laci explained to me how the Romans devised their number system. He drew for me all the Roman numerals: I is one, V is five, X is ten, L is 50, C is 100, D is 500, and M is 1,000. He

explained that this method made it necessary for the written numbers to grow, and grow, and grow . . . He showed me how a Roman might have had to multiply XVIII by LXXXII, and ultimately get the answer MCDLXXVI. For us today, this operation is simply 18 Ã 82 = 1,476, and we can do it quickly and efficiently. Laci challenged me to perform such a calculation in the Greco-Roman system and made me construct its multiplication table; it was so huge and complicated that it took me a week to do. Amazingly, he said, this inefficient numerical system remained in wide use in the West until the thirteenth century, when it was replaced by the numbers we know today.

1