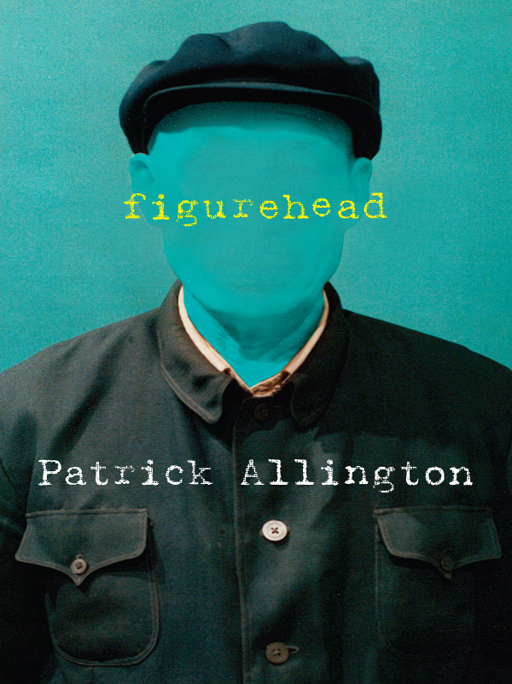

Figurehead

figurehead

figurehead

Patrick Allington

Published by Black Inc.,

an imprint of Schwartz Media Pty Ltd

Level 5, 289 Flinders Lane

Melbourne Victoria 3000 Australia

email: [email protected]

http://www.blackincbooks.com

© Patrick Allington 2009

A

LL

R

IGHTS

R

ESERVED.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers.

The National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Alington, Patrick.

Figurehead / Patrick Allington.

ISBN: 9781863954365 (pbk.)

A823.4

Book design: Thomas Deverall

Printed in Australia by Griffin Press

To Zoë

And to Douglas Allington, Jan Carpenter,

Lisa Allington & Matt Allington

Trapped in the side-wheel of a ferryboat, saving himself from drowning only by walking, then desperately running, inside the accelerating wheel like a squirrel in a cage, his only real concern was, obviously, to keep his hat on.

—James Agee on Buster Keaton

Contents

Yesterday I woke up expecting to be repulsed but instead I witnessed a scene

that so filled my heart with hope that I felt I might pass out. For yesterday

Mr Nhem Kiry – mouthpiece to the Khmer Rouge’s mass-murdering leader,

Pol Pot – tried to return to Cambodia’s capital, Phnom Penh, for the first

time in more than a decade.

You might remember – you probably won’t, that’s part of his genius –

that Nhem Kiry was a member of the Khmer Rouge leadership group that

threw a vast sheet over Cambodia in 1975. The conjurers practised their

tricks for nearly four years, but when their magic failed they set about eliminating

the audience. In 1979 the Vietnamese saviours arrived to banish Pol

Pot and his cronies, Nhem Kiry included.

Yesterday Nhem Kiry did not sneak into Phnom Penh like the criminal he

is. No. He arrived at the airport as a guest of honour. The United Nations

laid out the red carpet for him as the Khmer Rouge’s representative in the

burgeoning peace deal.

Peace? With the Khmer Rouge? Why not give Pol Pot the Nobel Prize

and be done with it?

But the good people of Phnom Penh, ordinary folk who live in slums and

ramshackled apartments, showed the UN a thing or two. They flocked to

Nhem Kiry’s new mansion. They taunted him and then they invaded his

house. They split his head open and found, to their surprise and delight,

that he bled just like them.

The United Nations called this moment a ‘setback in the march towards

peace and rehabilitation.’ I call it a courageous and truly democratic act.

And I’m proud to say I was there. I sweated in the crowd, I surged forward

with them, I screamed ‘Bloody murderer,’ I picked up a stone and I threw it

at a window. I pushed others aside so I could squeeze inside. I stormed the

stairs and I called out ‘Harrah.’

—Edward Whittlemore, ‘As I See It,’ syndicated column

Nhem Kiry’s face was a marvel. Despite decades of struggle and revolution – frustration, pain, fear and mud, victory disguised as defeat, defeat disguised as victory – his soft cheeks, mellow camera smile, gentle eyes and pale full lips remained great assets in his politician’s armoury. He knew it, too, and had for years cared assiduously for his skin. If these days he overdid the moisturiser and the wrinkle cream, he liked to believe that he was compensating for the years of jungle living, where no man’s complexion is unaffected. He did not care to acknowledge that he enjoyed the routine, the wiping and smudging, and especially the sudden coldness of the regenerating agents filling his pores. All the preening made him glow, and helped him present to the world the sweet eleven-year-old boy who lived within the tired 62-year-old veteran. Or so he believed.

After years of experimentation, Kiry had established that his skin responded best to Marie Weston’s No. 5 Replenishing Lotion. It wasn’t greasy. Even better, it was not tested on animals and it was fully organic. He could, in an emergency, eat it. But at fifty US dollars a tub, the extravagance bothered Kiry. Of course, he could have shovelled the precious goo from its sleek packaging into some battered old pouch. But that had never been his way. He valued his reputation for austerity, so every second week he exposed himself to the doubtful benefits of a cheap vitamin-E moisturiser.

Kiry was not vain. Rather, he knew that his work, his life, was about diplomacy and negotiation but also about image. At news conferences and ceremonies, especially when he shared the rostrum with foreign leaders, and during photo opportunities, he had to present himself as a member of the global club of political figures whose differences could be endured, massaged, maybe ultimately overcome, by the fact that they all dressed the same.

Still, spending big on Italian suits left him agitated in the change rooms of exclusive Bangkok boutiques and nauseous afterwards. He usually compensated by selecting a size too broad for his wiry frame, perhaps hoping to imply that he relied on hand-me-downs from ex-politicians.

At state dinners these days he not only had to look pristine, he had to be demure. He maintained a strict personal protocol. In particular, he never waved his cutlery around while he talked – there was usually someone in his vicinity who feared that his fork might end up embedded in their sternum. He avoided sudden movement, animated chat, or eating with his mouth open. You can’t leave anything to chance, he knew, when you’re selling a million and a half dead people.

Halfway between Pochentong airport and Phnom Penh, ready to join the interim government, ready to do everything within his power to help the UN keep the peace, Kiry pushed his wraparound Ray-Bans up his nose, fixed his smile in place, wound down the window of the Toyota all-terrain vehicle and placed himself on display. Beside him on the back seat his nervous bodyguards, led by the quietly agitated Ol, pleaded with him to sit back.

‘It’s too windy.’

‘You’ll get all dirty.’

‘You’ll mess your hair up.’

‘There might be snipers.’

Ol, whose war medals were his enormous shoulders, dead eyes and malaria, made himself ten years old again. ‘Please, please, can I sit by the window? I’ve never been to Phnom Penh.’

Kiry raised a hand. They fell silent and snooty, except for Ol, who redirected his exhortations to his front-seat colleagues. First, he pleaded with Akor Sok, Kiry’s chief aide, to intervene. Sok shrugged, though he agreed that in a perfect world the window should stay closed. He then wound down his own window.

Ol then asked Nirom, the chain-smoking driver, to slow down. Their other vehicle, full of bodyguards and luggage, was stuck behind a swarm of motorcycles and a truck full of pigs. Nirom, who had trouble keeping his cigarette in his mouth while he talked, did not reply or slow down.

A young woman swept past on a motorcycle, her long black hair flying behind her. She braked suddenly and drew beside the vehicle, causing a truck to swerve and the thirty or so passengers in its open tray to hug each other. The woman stared at Kiry. He removed his sunglasses and nodded at the chubby boy who was nestled between the woman’s thighs and the bike’s handlebars. The woman sniffed, loaded her mouth and spat. She hit Kiry on the bridge of his nose. Allowing for the wind and the speed at which they were travelling, Kiry had to admit she had a marvellous aim.

Kiry continued smiling at the child. Only when Ol, with a growl, leaned across and closed the window did Kiry shake his head and wipe himself with his handkerchief. Sok’s face turned red and Nirom chomped his cigarette in two, but the boy’s smile consoled Kiry. As a rule, children liked him. He didn’t talk down to them. He didn’t harangue them and then rub their ears. Not like Americans, who, he believed, had trouble telling their offspring from their dogs.

He tapped his breast and a piece of paper rustled. This was no important document, but a letter from an everyday American, Brendan H. Margaretti of Barron, Pennsylvania.

Dear sir,

it read.

My young son Jimmy saw a photo of you in our local newspaper. He was

delighted because he thought you were the real life Mowgli (the Jungle Book

is his favourite video). Anyway, I thought you might like to know that your

picture is now stuck to his wall, next to a drawing of Mr Snuffleupagus, an

imaginary creature much loved in this country. But I have to tell you, I

know a thing or two about what you’ve done in your life. I am going to keep

your photograph, even after my boy grows tired of you, because when he is

older I want him to recognise the face of evil.

Kiry had cut the letter in half and thrown the nasty piece away. He did not need CIA Nixonites dissecting his character. And only in a world overrun by UN committees could such correspondence ever have found him. But he kept the stirring portion of the letter in the top pocket of his suit, amongst his ballpoint pens. Often when he met a diplomat or a politician or a UN representative – and during the peace talks he felt as though he had met hundreds of them – he took it out and read it, always adding, with a shy but mischievous grin, and a raising of one eyebrow, ‘Of course, we Asians all look the same.’ At the end of one especially unproductive meeting he waved the letter about and suggested that the UNHCR fund his book proposal,

Children’s Letters to War Criminals

. It was a rare undisciplined act, but he was amused by the poorly concealed revulsion of all those in the room.

Kiry’s entourage was chaperoned by a police truck. Kiry had demanded a quiet entrance but once they reached the outskirts of Phnom Penh the police driver took possession of the very centre of the bumpy road. Horns squealing and lights flashing, oncoming traffic scattering, they became a parade.

The traffic was a tangle now. The genesis of a crowd easily followed them on foot. Kiry continued to fill the window, defiantly and proudly, though the blue-black glass now hid him. He spied quizzical looks, a glimpse of anger, a placard or two. If that’s the worst of it, he thought, I’ll be happy.

They were stuck for ten minutes on Street 182 near the Russian Market. A policeman with a lopsided grin dealt with the traffic by waving vehicles from all directions into the centre, where delicate, intricate calisthenics became necessary. The staccato honking of horns rang out, less road rage than a special language of negotiated settlement. As they inched forward, Kiry played tour guide to wide-eyed Ol.

‘That way is Independence Monument – Sihanouk put it up twenty years too early, of course, but it’s a nice enough piece of stone. Down there and to the right is the Royal Palace. I once lived back that way, with my mother.’

He paused to watch a one-armed man skirt around vehicles and run to them. The man slammed his fist on the hood and kicked a headlight. As he sprinted back to the footpath and disappeared into the crowd, the policeman applauded.

Eventually they reached the villa, a pleasant whitewashed two-storey rectangle. The waiting crowd numbered ten thousand. They held up signs – in Khmer, in English, in French – made from thin bedsheets or flattened cardboard boxes: ‘Khmer Rouge Killers,’ ‘Nhem Kiry Criminal,’ ‘Not Forgiven.’ They chanted, ‘Murderers, murderers, murderers.’ They shook their fists. Some of them fell on their knees and howled. They jostled each other and pushed against the shabbily erected wooden barricade.

The crowd closed in; the police fell back. Kiry’s gaze floated amongst the sea of young men, then focused on an old woman with a bad hip and orange teeth. She limped forward, clambered onto the bonnet and stared down Nirom, who took solace in a fresh cigarette. She wrapped her arms and legs around the bullbar. The purpose of her particular protest was unclear even to her many admirers, who cheered her anyway.

Kiry put his hand on Nirom’s shoulder and said, ‘Whatever you do, don’t run her down.’

Eventually, someone from the crowd – a hospital orderly who as a boy had fought for the Khmer Rouge against Vietnam, and as a youth for Vietnam against the Khmer Rouge – took hold of the old woman’s shoulders. It took him a moment to untangle her: she had quickly ceased being an active protester and had become a passive prisoner of her own intricate knots.