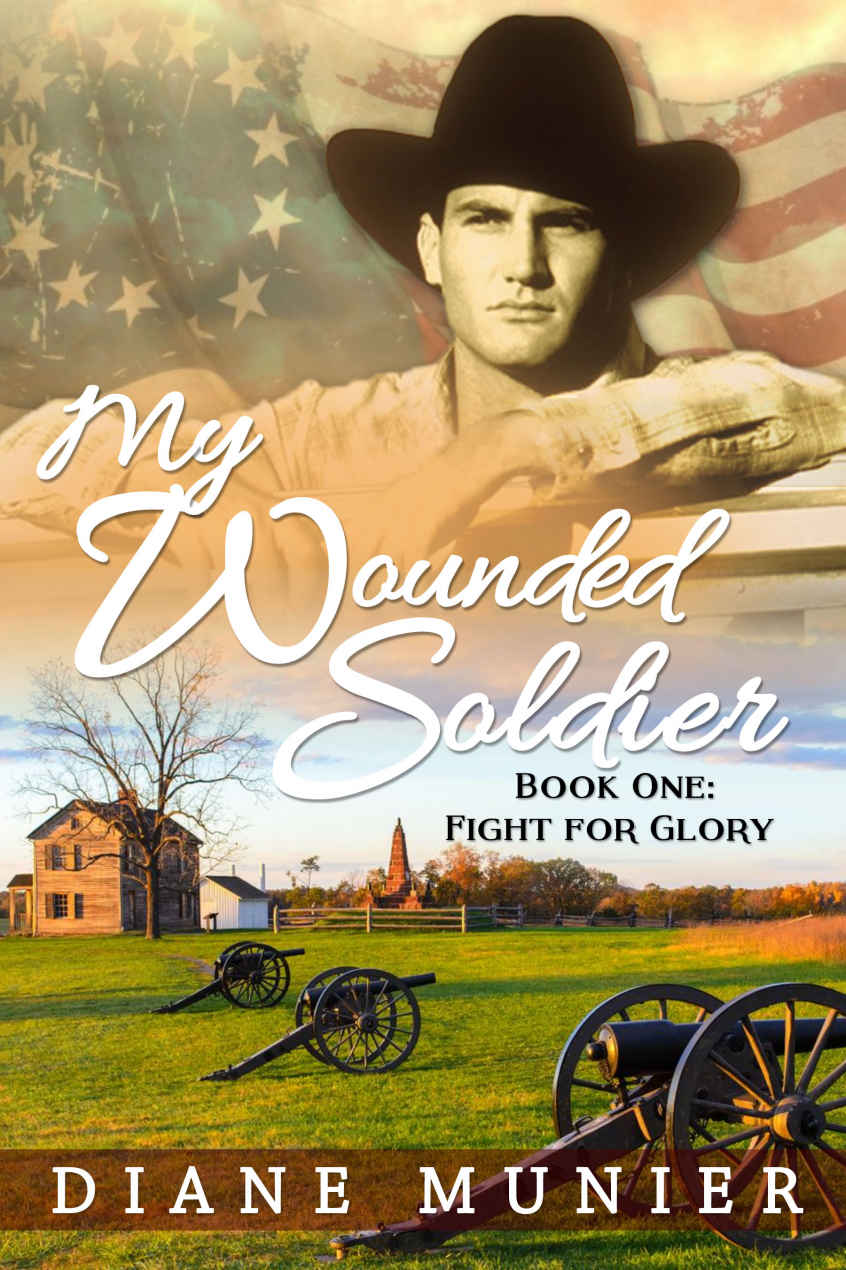

Fight for Glory (My Wounded Soldier #1)

Read Fight for Glory (My Wounded Soldier #1) Online

Authors: Diane Munier

My Wounded Soldier

Book 1:

Fight For Glory

Diane Munier

The characters

and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real

persons, living or

dead,

is coincidental and not

intended by the author.

Text copyright ©

2015 Diane Munier

All rights

reserved.

No part of this

book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any

form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or

otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher.

Published by

Diane Munier

Cover design by

Book Stylings

http://www.bookstylings.com

To my oldest daughter.

Prologue

Illinois,

1866

Addie

Varn

His head came

higher than the corn. Like a scarecrow free to walk this field, he parted the

dry green stalks. He sang an old battle song, had the word ‘glory,’ rolling

through it. I told Johnny to get inside, not that he ever listened when he was

curious.

When Stranger

cleared the crop line I saw a scabbard dragging. But the sword was in his hand.

And he raised it while he sang, calling out, “Richard Varn, Richard Varn,” in a

voice like doomsday, calling out, then singing.

Johnny nudged me

then, “Here Ma,” he said.

I took the

shotgun, mostly cause I couldn’t believe he had the pluck to be holding it

after all I’d told him not to. Then I swung it high and said, “That be all

right there, Mister.” But this veteran did not listen, as they sometimes did

not. In their heads, many not right from the war, and the country running with

them while they tried to find home. It was frightening times.

“Right there,” I

said, the baby in me kicking high this morning, making it hard to breathe, and

now this. Well.

He stopped then,

like he was in a parade. He moved that sword and brought it over his heart. “Back

home our crops didn’t make three years and we owed the Varns

cause

Charles held credit, he did. That one say there’s a way to wipe it clean, that

slate of debt I couldn’t pay. I went to war for his boy Richard, see? I left my

missus and children but fate and the Lord did conspire and I was taken at Ivy

Mountain. We died in great numbers in captivity. But I lived through and spent

the years in deprivation Richard Varn should have spent. When I got out…my wife

moved west, they said.

Took my children.

Now I am the

man owed, and I come to settle,” he

said,

his

attention sharp on me.

“You lay down

that sword and I’ll bring you bread and butter beneath that Sycamore,” I said

quick

. The Lord and this gun gave me courage.

Johnny had the

wits to go for his pa. Richard followed him into the yard now. He carried two

buckets from the milking, but he set them down. “What’s this?” My husband’s

voice was sharp, for he did not take to these strangers.

But he did not

take to his wife holding the gun on a man, and he made a motion with his hand

for me to stop my foolishness and lower the weapon.

I did what he

asked, but I was ready to lift it need be.

“You Richard Varn?”

Stranger asked.

“That’s me,”

Richard said. His hands moved to his hips as if he’d had enough.

“You are the one

whose cross I bore. You took all that I was…all that was mine.” He lunged

toward Richard, a swift motion, two hands lifting the sword. An arc of red

ripped down my husband, across his face and neck and chest, so deep.

Johnny screamed,

but it was that sword lifting to finish my lad that brought the weapon steady

on my shoulder. God’s hand on mine squeezed that trigger. Red drops splashed in

the sun as Stranger’s hat blew away with a goodly piece of his head.

His body fell to

the earth and my son blinked at him…at me.

“It’s done…,” I

said, panting hard.

And then pain. I

dropped that gun, and I reached for Johnny who was stuck there staring at the

two beyond help.

“Hear me Johnny!”

He looked at me,

his little body heaving with his breaths.

“Run yonder. North

field,” I said. Then I knew not how but I was on my knees. I was gripped in

pain again, and I was locked in it unable to move. I could not even lift my

head to see if Johnny had

hightailed

it for help. But

I knew that one was home from the war, that oldest son who never spoke to even

say howdy. I’d seen him riding high on the wagon just that morning in the north

field. I wagered…he’d be the first one here. I just knew. For he’d been a

soldier…’my wounded soldier,’ his mother had called him when she told us her

husband had gone on the train to fetch him home.

If there were

more of these strangers skulking about…he would know what to do.

“Tom,” I said,

for that was his name. I could lift my head now, and my son was still staring. “Johnny…

find

Tom.”

I felt all of

life gush between my legs then, and the sharpest most sickening pain. I could

not birth on this sad porch. I must hold on…and help would come.

Tom

Tanner

Chapter

One

I would never

look at a field the same again. For all of life seemed different to me now. I

did not trust the quiet. It used to stretch on, when I was young. But now I did

not trust it, and knew it held all of the ingredients for chaos that could come

so quickly, in a turn, a moment.

Death.

I had just

finished the bread and meat Ma had packed for me in the wagon. That soft white

bread I could not stuff myself with enough to silence my thoughts or fill the

empty craving. I wasn’t worthy of the bread, the hands that kneaded it with

hope, nor the fire that baked it.

I was no sooner

done with my hourly chaw of self-loathing when I picked up a call…a young

voice.

Too young for such a pitch, such a word, my name.

It was not my

brother Garrett. But I heard him sometimes…on the wind.

Smelled

him, too.

Saw him in some men…tall ones, strong like him, walking

loosely and free. But this call was younger, and I thought I heard it again.

I rounded the

wagon and saw him.

A lad coming on, running.

“Mr.

Tanner,” he cried. I hurried to meet him. “My ma,” was all he could say, over

and over, hands on his knees. But when he got going, I picked him up and ran

for the wagon. Though I could not clearly understand him, I heard enough of the

words I hoped to never hear again. Soldiers and guns and killing.

He was the Varn

boy, the one who favored the mother. He was dark and freckled, big brown eyes. I

had seen her at meeting. She had rattled me enough I took note.

Only because my ma went on.

My sister too.

There was Jesus and the Mrs. Varn.

But now…the lad

sat beside me, as I nudged this old mule to do more than saunter. She was past

her prime and in no hurry. I’d only brought her today because the work was

light.

I watched the boy

from the corner of my eye. He stared ahead, a white grip on the seat.

The boy had told

the story then stopped talking altogether. I didn’t think I could send him to

the farm on his own. He looked spent, and if there was trouble, he shouldn’t be

trouncing around until I understood what to look for. I had my rifle, I was

rarely without it. So the boy needed to stay near.

I pulled up to a

gruesome scene. The boy was keening, a bad sound. He was rocking on the seat. I

told him to lie in the bed of the wagon. I spoke firmly, and made him look at

me.

But he pointed to

the porch, and there was his ma, her dark hair spread around her spent form. She

looked tossed on that porch like a rag doll. I lost my breath for fear she was

dead, too, but she moaned then and started to move.

So I grabbed that

boy from the seat and all but tossed him in the wagon’s bed. “Lay still. Soon’s

I can I’ll help you out.” I took my rifle and went to the woman. I could tell

the men were gone.

Holy cow she was

big with child.

Looked ready to foal and with the moaning.

I needed Ma. There was no possibility…I’d rather face those dead bodies any

day.

I knelt by her

side. She opened her eyes and said my name. I couldn’t have been more surprised

if she was dead.

I stood my rifle

against the house, also retrieved her shotgun and did the same. Then I scooped

her up because she wasn’t heavy at all, light like my sister.

I pushed through

the door with my shoulder, looking at her, so pretty and looking like almighty

hell.

This poor thing.

I went to the bed in the far

corner and laid her on the quilt. I ran to the door then. “Boy,” I called,

grabbing the weapons, “Get on in here.” When he didn’t show I said more firmly,

“Boy!”

He popped up then

and scrambled over, hitting the dirt hard, but on his feet, and he came

running. I wanted him in the house where I could make sure he was safe. This

woman didn’t need to lose another while birthing. Dear God, birthing.

Just me and her and the big blue sky.

So I set that boy

a job. I had him peel about six potatoes so she’d have some soup when she got

through pushing out this baby. And I wanted his mind to stay. Setting a task

was the way to nail him to something real.

Then I hung a

quilt from the rafters to block his view. I fed her a little water, but she was

poorly. I debated sending that kid over to get Ma, but my

gut

said don’t

do it. So I rubbed my hands together, and took off her shoes.

She had little feet and I blushed seeing them so small and dainty in my hand. I

did not know my preference for little toes before now, but another pain gripped

her and I came to my senses and repented as I told her I was sorry, but she

couldn’t have a baby wearing her bloomers. So being careful to keep the skirt

in place, I tried to reach beneath its bulk and get a hold of the bloomers,

which were split so she could make water, and she already had, lost the water,

but still I knew this was going to get real messy, so I pulled her bloomers

down, and tears came to my eyes I swear thinking of the after, that’s if we

both lived through this.

But I got them

off without seeing anything but her dainty legs shaped so fine I could call

myself nothing but sinner as I tried to blot out every idea I ever had about

procreating and such.

I checked on

Johnny and he sat at table hacking at those potatoes. I told him to fetch some

carrots too, and work on those and I wanted them done right. I felt so guilty,

and I don’t know why. I didn’t ask for any of this. But God was always giving

it to me anyway. I didn’t deserve nothing good, but what a fix.

I got a rag and

the whole bucket of water and told him,

“Don’t be looking out

that window neither.”

Cause I didn’t want him studying his pa that way.

I went behind the

curtain, and she was worse it seemed, eyes closed and whimpering, and I wet the

rag and washed her face, then her neck she was so sweaty and distressed. I was

speaking soft to her, saying embarrassing things I thought might soothe her, I

didn’t know. But I’d talked to a dying man or two and it served me now.

In the next hour

we got past it all. Her skirt was off and on the floor. I had her knees bent,

and was constantly having to bring her leg out of the way. She was screaming

and writhing, then so silent I feared she was dead. Her woman parts were

widening so swollen and looking ready to pop. I had seen animals birth…all my

life. So this was not so different, and so very different.

I was studying

down there, praying for that head to show. She was such a frail looking thing,

so dainty, and yet so strong, I shuddered to think how she hurt. I never wanted

to see such pain again, but here it was, and I told myself it was good.

If she lived.

I hoped I didn’t

have to reach up there and turn it around. I’d had my arm up a cow or two, even

a horse, but there was no way I could mess around in this tiny woman, and hurt

her like that…, “Oh God, I know my prayers are rotten to you…but for her

sake….”

Her little head

was thrashing. “Tom,” she screamed.

And then a

miracle happened. She opened up, and I saw the child’s hair. “Missus,” I said,

“you’re doin’ so fine, girl. You’re so fine. Just push it out now, it’s just

like it should be, honey.” I was so danged relieved I could have danced a jig

if I wasn’t afraid she was going to rip apart and bleed to death on my watch.

Her little parts

were straining, parting like the Red Sea, and before I knew it a bigger oval of

the infant’s hair showed.

“That’s it,

honey. You’re the strongest woman I know. My ma would be so proud of you.

You’re almost there now, darlin’ girl.

Don’t you be

afraid.

You’ve got to push. Put some muscle in it now.”

“She

grit

her teeth, and I gave her my hand, and she squeezed the

juice out of it, and I kept telling her to come on like she pulled the plow

through mud and stone, and she pushed and I had to let go and catch this baby.

Its whole head and shoulders were out now, and I turned it gentle as I eased it

out of her, and my life got washed in one moment. I knew that somehow God was

telling me I wasn’t the most miserable bastard that ever lived. Cause I had

touched heaven, and done a good thing…like a priest or some-such.

So I set that

baby on her mama’s stomach, and Missus looked at that girl and laughed a

little, then at me, and I had this life cord and the business still running

into her to deal with, but for a moment, we just looked at each other and she

said, “Thank you.”

And I

said…nothing in the face of such beauty as that mother and her child. I couldn’t

speak.