Fiction Writer's Workshop (17 page)

Read Fiction Writer's Workshop Online

Authors: Josip Novakovich

What you learn from listening to television is the ability to experience things self-consciously. Once you've studied literary dialogue for a long time, the lack of pretense in television may seem somehow refreshing. Still you have to set rules for yourself. Understand what you don't have to do (you don't need easy resolutions!) and you will be able to see what you must do (complexity is your friend). Some rules, from listening to television.

Don't rush.

No need to make your dialogue do the work of closure. For you, the fiction writer, the commercial isn't coming up. There are few long speeches in commercial television. No monologues in any real sense of the word. That's because television breaks meaning into small bites, easily digested, to make the message clearer. When you sit there, blindfolded, you'll be amazed at how quickly people talk and how little real silence there is. This should translate in your fiction to

don't rush.

Leave some space.

Resist the urge to put it all in words. On television, the characters often say things that just happened ("Who was that on the phone?" "That rock almost killed you! One step closer to the edge and wham!").

Resist exposition.

Television writers have viewers dropping in at many different moments of the show. One of the things the creators must do is allow each line of dialogue to have some capacity as a piece of setup, or as exposition. Exposition has a place in stories of course, but it ought not to leak into the dialogue time and again.

Brady-ized Dialogue

I often see moments in early drafts of stories where dialogue is used to stretch scenes. There's really no need for this. There are too many things—sounds, thoughts, distant trains—that ought to fill up the lulls within a story. When you start to use words in that way, you are merely filling the emptiness with empty moments. I think a lot of this trouble comes from television, which by nature and necessity has few moments of real silence. Movies are different (and we'll touch on this later), but in television the camera is rarely off the character, and even more rare are moments when that character is allowed to be silent or still. Most programs are an endless string of chatter. When this effect slips into a written dialogue, I say the dialogue has been Brady-ized— reminiscent of a conversation from the old

Brady Bunch

show.

As a teacher I see a lot of Brady-ized dialogue. I can drum it up pretty quickly, because I see the characteristics even in fairly brief exchanges. The key here is that each line has a purpose in the propulsion of plot, conflict and theme. There's generally little attention to timing, music or mystery, three great keys to character within short fiction. While reading the following example, write down the calculated effect of each exchange. I won't set up the scene with any more than a location.

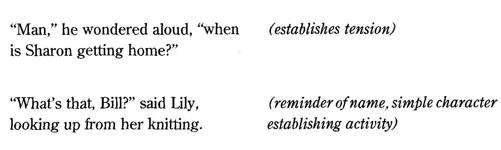

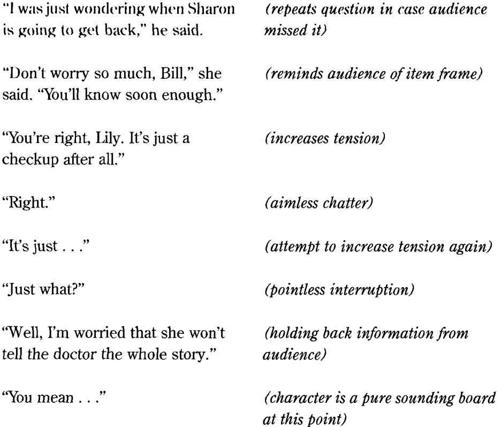

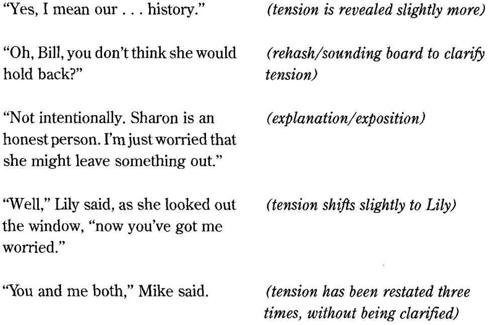

"Man," he wondered aloud, "when is Sharon getting home?"

'What's that, Bill?" said Lily, looking up from her knitting.

"I was just wondering when Sharon is going to get back," he said.

"Don't worry so much, Bill," she said. "You'll know soon enough."

"You're right, Lily. It's just a checkup after all."

"Right."

"It's just. . ."

"Just what?"

"Well, I'm worried that she won't tell the doctor the whole story."

"You mean . . ."

"Yes, I mean our . . . history."

"Oh, Bill, you don't think she would hold back?"

"Not intentionally. Sharon is an honest person. I'm just worried that she might leave something out."

"Well," Lily said, as she looked out the window, "now you've got me worried."

"You and me both," Mike said.

You might be asking yourself, Does he think that's good television dialogue? The answer is no. I think that's Brady-ized dialogue in that each character pulls the other along. Every line of dialogue invites, virtually demands, the next. There is no rhythm or pace or surprise. It's guilty of some of the same flaws that bad television writing falls prey to, for whatever reason, good or bad, the sort of stuff that creeps into the worst daytime television writing and the weakest television movies. Think of the list of rules gleaned from listening to television. This dialogue breaks them all: It rushes the tension forward, it leaves no room for silence, it is heavily expository. Every line in the exchange is a servant to plot and nothing more. There isn't a drop of character or place. It's chock full of reminders and rehashes. While you can sense a story all around it (maybe not a good one, but a story nonetheless), this is a dialogue that doesn't serve the heart of the story— unless that heart is a vault of dim-witted, ironic posturing. Check out the way I chart this mess.

There's not much I can do if you like that. That is

not

how people sound. That is the way television sometimes sounds. If it sounds like

that to you more than once a week, turn it off! (There, I did give you a hard-and-fast rule after all.) Also,

don't chart your own character's dialogue.

There are a lot of books on screenwriting and television writing that claim every line of dialogue should have a purpose. That is lockstep thinking. Plain and simple, in any medium, good dialogue sounds like people talking. They may be intensely witty; they may be evil; they may be a widowed architect with three sons who marries a widow with three daughters, all of them with "hair of gold, like their mother." But they should sound like people talking. So don't chart. It makes you too aware of purpose, of direction, and forces an element of calculation into the words of your characters. Your calculation, not theirs.

If you do chart your dialogue, think of it as a party trick and nothing more. People do not constantly invite one another to "deliver" the next line. Not in fiction, not in life. In fiction writing, you are just mowing down the story for the reader when you engage your characters in dialogue that simply serves to propel the plot line. Okay, I've changed my mind again, chart it if you want. But if it can be clearly charted, you might as well throw it out and start over.

Good Television

So what's to like about television? I've just gone on a harangue about bad television, but there are skills you can learn from watching television: economy, accommodation and timing.

Economy

refers to the need to be measured and clear, to take two or three story lines through a relatively short written space. Watch an episode of

Seinfeld,

for instance. In a good one, there are four story lines going through the text of the show at once. Each character carries one subsequent line of conflict from a gathering in the central location into a series of individual scenes, which play out the string. This blends dialogue into the pacing and structure of the show. On this show, tag lines are used to call up the same laugh over and over again; it works too. The lesson to take into your fiction writing is to learn to pinch your language to a minimum, to think of fewer words as being capable of doing more.

Accommodation

refers to accommodating the needs of the form and to the fact that many shows have more than one writer, as well as an actor taking up the writer's words. Writers rely on actors for reaction shots, for reliable delivery, for their ability to use the scene around them in some creative fashion. Here, the element to take to your fiction is to remind yourself that everything does not have to be done with the spoken word.

Timing

is often in the hands of the actors, but without the scripts, there would be tons of tiresome improvisation. Good timing in the written language is the first step to good timing on the small screen. Watch "The Dick Van Dyke Show". The exchanges in the office are fine examples of the complex effect of layering dialogue, of having several people speak at once. Here, it might be helpful to tape and script out an exchange or two. You'll be surprised at how clipped the dialogue seems on the page. Notice how often people repeat the last thing they heard. It gets laughs. Again, these are reminders that the writer is leaving room for delivery (accommodation) while at the same time working within the confines of the form (economy).

In most television writing, you'll see some evidence of one of these factors. In good television writing, you'll see all three. How do you use this in fiction?

Be aware of the pattern of dialogue. Use repetition.

On television, a character will often repeat the last thing another character says, merely to string out the laugh. But sometimes these patterns of repetition are what make the laugh. The language can be fun. Remember, you don't always have to explain.

Watch for what you don't have to do.

On television, the scene is often the background of the story. Sometimes the words people speak can be the story. Let the words deliver themselves. Avoid adverbs on the end of dialogue tags, as this just becomes a way of defining delivery. If the words are right, the reader will hear them without worrying about the delivery.

Don't sequence scenes around dialogue.

Story lines on bad television often begin with someone arriving—coming home from school, walking into the kitchen, returning from the grocery store—or end with someone leaving, followed by a reaction shot. Again, these are functions of form. The writer is allowing the story to open at the moment, reminding the audience of the new start. It's clumsy and trite, and generally sells the audience short. It's one of the parts of the formula that often gets transposed onto otherwise good stories. A dialogue, like a scene, does not need to take us from entry to exit.

Good television, like good fiction, works to create variations: ending dialogues without stretching the text, without people straining to say good-bye or walking out; opening stories in the middle of things. Either case is an example of how television writers are working to keep the character's words from defining the sense of opening and closure of story and scene.

READING MOVIES

Aren't movies a whole lot better than television? To my mind that's like asking: Aren't bagels better than donuts? Same basic shape, similar function, completely different taste and texture. Bagels are better for you, but sometimes you want a donut. On the other hand, the well-dressed bagel can be a meal, whereas the sugary donut rarely suffices. Eat too many donuts, you get fat. Eat too many bagels and you spend all your time arguing the inane question of who makes the best bagel.

For the fiction writer, movies offer constructive models, a chance to see dialogue—often the sort more related to the shape of fiction— coming out of the mouths of talented actors. There's a reliability to this that is undeniable. Good actors make things work. Good writing is improved by good actors; whereas, bad writing can't be masked by the best efforts of a great actor. I have friends who are actors; I respect their work. I am amazed by it. But I would say straight to their faces: The writing is the thing. Once you've read more than a few screenplays, you start to see they are the tautest, most disciplined pieces of writing in existence. The writer goes to the movies to study. Then he reads the movies to study some more.