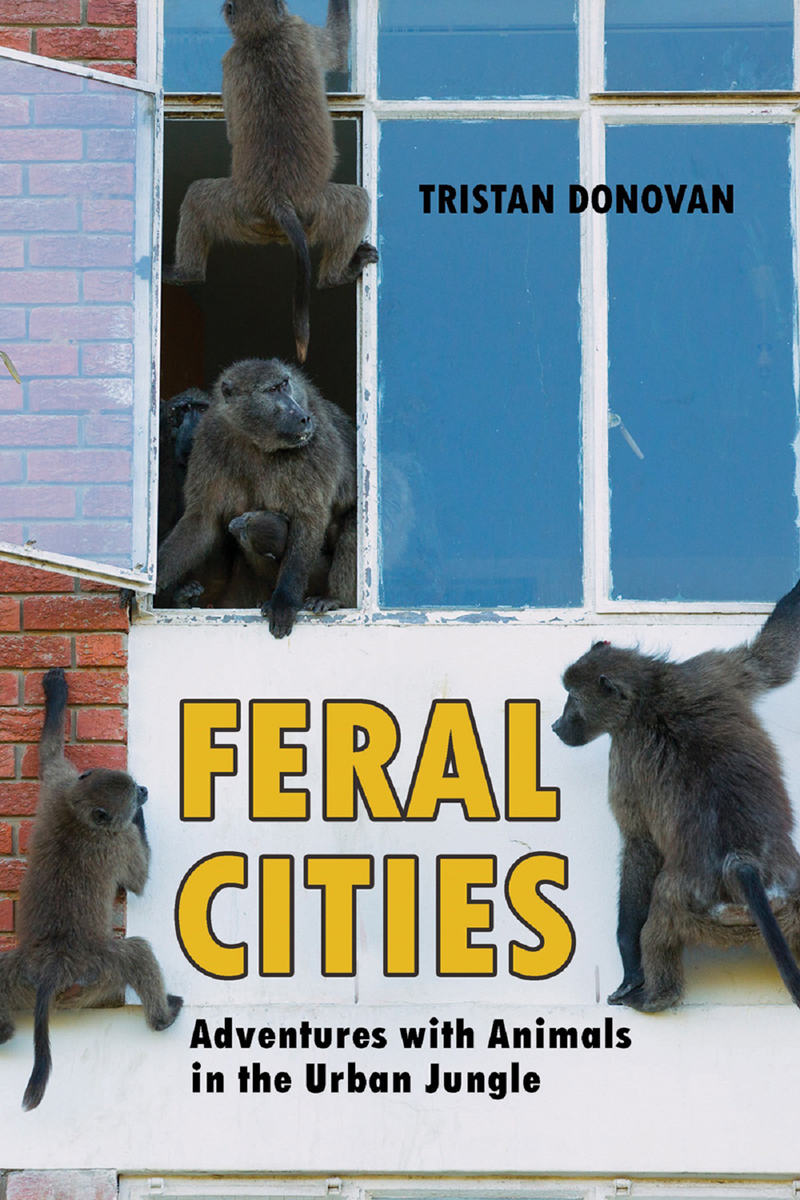

Feral Cities

Authors: Tristan Donovan

Copyright © 2015 by Tristan Donovan

All rights reserved

Published by Chicago Review Press Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-56976-067-3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Is available from the Library of Congress.

Cover design: Rebecca Lown

Cover photo: Chacma baboon group raiding apartment building, South Africa.

Cyril Ruoso/Minden Pictures

Interior design: Jonathan Hahn

Illustrations: Tom Homewood

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

To my wonderful parents, John and Maria Donovan

Â

1

Â

Hot Tub Snakes

On the Trail of Rattlesnakes in Phoenix

Â

2

Â

Voodoo Chickens

Miami's Chicken, Snail, and Snake Invasions

Â

3

Â

The Great Sparrow Mystery

Fighting Starlings in Indianapolis and Saving Sparrows

Â

4

Â

Street Hunters

Living with Boars and Raccoons in Berlin

Â

5

Â

Romancing Coyotes

Looking for Coyotes in Chicago and Los Angeles

Â

6

Â

Thieves in the Temple

Monkey Trouble in Cape Town and Delhi

Â

7

Â

The Lion of Hollywood

Tracking Leopards in Mumbai and L. A.'s Cougar

Â

8

Â

Singing a Different Song

Hanging Out with the Parrots of Brooklyn

Â

9

Â

The Chicago Bird Massacre

Saving Migratory Birds in Downtown Chicago

11

Â

Tunnels of the Bloodsuckers

The Rats and Mosquitoes Lurking Under London

NYC Cockroach Investigations and Bakersfield Kit Foxes

Index

On the Trail of Rattlesnakes in Phoenix

Bryan Hughes lives a double life.

Much of the time he is a mild-mannered web designer, tinkering with computer code and honing the look and feel of websites. But there's another Bryan, one his IT colleagues are only dimly aware of: Bryan, the rattlesnake catcher of Phoenix, Arizona. “I don't tell anybody in my tech life what I do with the snakes, really,” Bryan tells me as we drive down Piestewa Freeway. “I'd rather not have people think I'm weird or something. There was a snake in the parking lot at work one day, so I went and caught it. All my coworkers' jaws were wide open. They had no idea. They thought I was going to die.”

We've been driving the highways of Phoenix for a few hours now, circling the fast-growing city's patchwork of sprawling new developments and oven-hot Sonoran Desert, where columns of tall saguaro cacti reach into the sky like spindly fingers. From the back of Bryan's truck comes the sound of angry hissing from a rattlesnake that, thankfully, is securely stored in a bright red tub that was once a pool pellet container.

We're killing time, waiting for a call. We've been waiting all morning, hoping that someone, somewhere in this city of more than four million people is going to have a rattlesnake encounter. So far, all we've done is release one of Bryan's previous catchesâa light brown-and-yellow southwestern speckled rattlesnake. It had slithered into someone's backyard to drink from the swimming pool. Now it gets to make a new home in a remote corner of one of the city's large desert parks.

As we head down the freeway, I ask Bryan what got him into rattlesnakes and to found Rattlesnake Solutions.

“Dinosaurs,” he says, after a brief think. “That might have been the start.

“I really loved dinosaurs and bugs as a kid. When I was five, my grandma gave me a little 35mm camera. I got some ants and put them into all the spiderwebs in the yard and took pictures of them. They were the worst pictures, but I put them on a board and then got all the adults in the neighborhood together in grandma's living room and gave a talk about spiders. So I was kinda born to do this kind of stuff.”

The young Bryan soon discovered that the problem with dinosaurs is that they're extinct. “So when I got done reading all the dinosaur books, I got started reading the reptile books and it was just fun. I'd go out and catch them a lot. I just haven't grown out of it, I guess. It's like people who have Lego when they're young and grow up to be architectsâsame kind of thing.”

And being a snake catcher in Arizona is about as good as it gets for a reptile fan like Bryan. “I really love my job doing design, but I like doing this more. It perplexes my peersâthey think I'm just doing pest control, like I'm going out spraying for termites or something. But there's lots of excitement, and I love the snakes. When I was a kid, I couldn't dream that I would have the entire city of Phoenix looking for snakes for me.”

Trouble is, not many people like snakes, let alone rattlesnakes. In fact, they are hated.

Bryan tells me about the rattlesnake roundups of Texas, where people catch the reptiles by the thousands by pumping gasoline into snake burrows to force them out. “It's the most disgusting practice. They gather ten or twenty thousand of them and take them to a big festival under a tent, and people pay to come,” he says. “If you're a kid you can pay five bucks and you can decapitate a rattlesnake or skin them aliveâthey hang them up by their head and rip their skin off. It's awful, and if it was any other animal there is no way it would be legal.”

Rattlesnakes, he tells me, don't deserve their bad reputation. They are social animals that give birth to live young. They even have friends. “They will prefer to sit next to a particular snake and not another one. If you put them all in a room they will always find each other to hang out, and they can recognize siblings, that kind of stuff. They're mothers, not just things crawling around, pooping out eggs at random.”

And although they areâof courseâvenomous, rattlesnakes use their poison defensively. When people get bitten, says Bryan, it's usually because they were trying to be macho. “They're often people who say âI grew up on a ranch,' people who hold the snakes up by the head and take selfies or say they are protecting their kid by whacking a rattlesnake with a spade, but that's dangerous.

“People build up these imaginary threats because in a city the biggest threat is your favorite coffee shop running out of doughnuts. I try to tell them to walk away and have a mutual respect for their foe. That works well because that gives them a good story to tell their buddies at the bar.” Teenage girls are the worst, he adds. They encourage their boyfriends to do stupid things because they want rattlesnakes killed.

Rattlesnakes do seem to make people go a bit crazy. Bryan tells me of the time a rattlesnake was seen on the grounds of a school in Mesa. “The janitor pulled out a handgun and shot it. They were all freaking out about the snake, but what about the janitor with the gun? Does anyone care?”

Another time the cops called Bryan after an iguana, probably an escaped or released pet, was found in downtown Phoenix. “It was kind of funny. There were these three cops there, one of them has a gun drawn, and there's this baby iguana up on a mailbox, hissing,” he says. “It jumped off the mailbox and this cop ran like a little girl, like tippy-toe running away. I caught it and found a sanctuary for it.”

Just then, Bryan's cell phone rings. I listen in, my fingers crossed for a rattlesnake.

“Is it rattling?” asks Bryan. A pause. “OK. I'll be there very soon. Just keep an eye on it.” He hangs up, turns to me and says: “We've got a rattlesnake.”

Bryan punches the zip code into his GPS and hits the accelerator. It feels like we're in the Batmobile and the searchlight has just been switched on.

The journey that took me to Phoenix began more than five thousand miles away, back home in the United Kingdom. For months British newspapers had been filled with strange tales about London's red foxes.

There was the sleeping IT worker who turned over in bed to cuddle his girlfriend, only to find a fox that had gotten in through the cat flap and snuggled up to him. Another man found himself having a standoff with one of the reddish-brown creatures over a stick of garlic bread. After trying, unsuccessfully, to frighten the fox by waving the stick at it, the man threw the bread at the animal, which promptly grabbed it and left. Then there was Romeo, the fox found on the seventy-second floor of the Shard, the UK's tallest skyscraper. The tower was still being built at the time, but the fox had climbed up the stairs and managed to survive by eating scraps of food left behind by construction workers.

Some stories were worrying rather than cute. In south London a couple fought with a fox in their living room after it entered their

home and attacked their cat. In Hackney, a fox entered a Victorian terrace home and mauled two nine-month-old babies.

Almost everyone I knew in London had a fox story, from the fox that goes begging for food at summer BBQs in Clapham to the group living next to a gas reservoir that use my friend's garden as their toilet. The stories got me thinking about my time studying ecology at university in the 1990s. Neither the course nor the academic journals had much time for the city, which seemed to be regarded as a nonhabitat, devoid of wildlife. As a Londoner, that always seemed wrong to me. Sure, much of the British capital is a landscape of road, brick, and concrete, but the city of my childhood certainly wasn't lifeless.