Feminism (11 page)

Authors: Margaret Walters

Tags: #Social Science, #Feminism & Feminist Theory, #Anthropology, #Cultural, #History, #Social History, #Political Science, #Human Rights

There was, of course, nothing like complete male suffrage at this period. Even as late as the 1870s, only about one-third of adult men could vote, and though the Reform Act of 1884 increased that number, still only somewhere between 63% and 68% of men were enfranchised. But, ironically, the legal position of women had actually worsened with the Reform Act of 1832, which specifically

Fightin

excluded women by substituting ‘male person’ for the more inclusive and general word ‘man’, which, it could be argued, might

g for th

be interpreted as meaning ‘human being’. In the same year, a radical known as ‘Orator’ Hunt was asked to present parliament with a

e v

o

petition (which had been drawn up by a wealthy Yorkshire spinster

te: su

called Mary Smith) arguing that ‘every unmarried female

ffr

a

possessing the necessary pecuniary qualifications’ should be

gists

allowed to vote. The petitioner, Hunt pointed out, paid taxes like any man; moreover, since women could be

punished

at law, they should be given a voice in the

making

of laws, as well as the right to serve on juries.

But the struggle for the vote was only beginning, and it was never straightforward. There were divisions between those arguing for adult suffrage, and those who wanted to campaign simply on behalf of women. And amongst the latter, there was disagreement about

which

women should be enfranchised. Many early demands for women’s suffrage concentrated on spinsters; Frances Power Cobbe, for example, argued the case for women property owners and taxpayers. These limited demands were partly a matter of tactics (if

some

women won the vote, it would at least set a precedent, which might later be more easily extended), but it was often assumed, 69

dismissively, that a wife’s interests were identical with her husband’s, and that giving her a vote would simply mean handing a second one to the man of the household. Some women believed that the passing of a married women’s property act would prove more immediately useful to them than the vote. On the other hand, Mrs Humphrey Ward expressed her anxiety that, if spinsters were allowed to vote, it would mean that ‘large numbers of women leading immoral lives will be enfranchised, while married women, who, as a rule have passed through more of the practical experiences of life than the unmarried would be excluded’. One member of parliament remarked sarcastically that if spinsters were enfranchised, it would be rewarding ‘that portion of the other sex which for some cause had failed to be womanly’. Other opponents of female suffrage argued that only a man might be called upon to fight for his country, and that ‘gives him a claim of some sort to have a voice in the conduct of its affairs’.

The debate offers some odd and revealing glimpses into attitudes

minism

towards women. Thus in 1871, the political philosopher Thomas

Fe

Carlyle remarked that

the true destiny of a woman . . . is to wed a man she can love and esteem and to lead noiselessly, under his protection, with all the wisdom, grace and heroism that is in her, the life presented in consequence.

And a great many women, as well, accepted the notion that by nature and God’s decree, women were different to men. God meant them to be wives and mothers; if they deserted their proper sphere, it would lead to ‘a puny, enfeebled and sickly race’.

Progress, perhaps inevitably, proved very slow. Indeed, very many prominent women dismissed the vote as relatively unimportant, insisting, sometimes a shade disingenuously, that they, personally, had never suffered any disabilities from its lack. Florence Nightingale announced in 1867 that ‘in the years that I have passed 70

in Government offices, I have never felt the want of a vote’, and though she later conceded its importance, she always felt there were other more urgent problems facing women. The successful writer and journalist Harriet Martineau insisted that ‘the best friends of the cause are the happy wives and the busy, cheerful satisfied single women . . . whatever a woman proves herself able to do, society will be thankful to see her do’.

Beatrix Potter attributed her own ‘anti-feminism’ to ‘the fact that I had never myself suffered the disabilities assumed to arise from my sex’. The Liberal Violet Markham came up with an evasive paradox: many women are clearly ‘superior to men, and therefore I don’t like to see them trying to become man’s equals’. By 1889, the popular novelist and journalist Mrs Humphrey Ward was claiming that ‘the

Fightin

emancipating process has now reached the limits fixed by the physical constitution of women’. Queen Victoria was sometimes

g for th

hailed by suffragists as an example of what a woman was capable of; Barbara Leigh Smith, for example, pointed out that ‘our gracious

e v

o

Queen fulfils the very arduous duties of her calling and manages

te: su

also to be the mother of many children’. But Victoria notoriously

ffr

a

exclaimed in horror against the ‘mad wicked folly of women’s

gists

rights’.

The Langham Place circle around Barbara Leigh Smith played an important part in the long struggle for the vote, as in so many other campaigns. Early in 1866, they organized a suffrage petition, with 1,499 signatures, which argued that ‘person’ should be substituted for ‘man’, and that all householders, without distinction of sex, should be enfranchised. Emily Davies, who had worked so effectively for women’s education, formally handed the petition to John Stuart Mill, whose book

The Subjection of Women

had just been published, and he presented it to parliament in June 1866. It was – as they had expected – defeated, by 194 votes to 73; but even this was welcomed as an encouraging start. Its effectiveness was perhaps confirmed by the number of hostile responses it attracted.

The Spectator

, for example, sneered that no more than twenty 71

women in the country were politically capable; women in general made political discussion ‘unreal, tawdry, dressy’.

In October 1866, Leigh Smith and a group of friends met at Elizabeth Garrett’s home in London to form a suffrage committee, which, the following year, became the London Society for Women’s Suffrage. They organized petitions which brought together more than 3,000 signatures. Leigh Smith also produced a pamphlet on

‘Reasons for the Enfranchisement of Women’; several establishment papers, including the

Cornhill

and the

Fortnightly

Review

, refused to print the argument for women’s votes. Around the same time, a woman called Lydia Becker formed a similar society in Manchester; she had been drawn to the cause after hearing a paper given by Leigh Smith; she formed a local Women’s Suffrage Committee, and in 1870 founded the

Women’s

Suffrage Journal

. Pro-suffrage groups soon followed in Edinburgh, Bristol, and Birmingham; they proved important in keeping the issue alive through the decades ahead, and keeping up pressure

minism

on parliament. Public meetings were arranged, particularly in

Fe

London and Manchester. Richard Pankhurst, who was involved in the Manchester group, had founded the

Englishwoman’s Review

in 1866, and this helped publicize the suffragists’ cause.

It was perhaps inevitable that the suffragists were at times plagued by disagreements, particularly about tactics; Barbara Leigh Smith soon withdrew from any formal participation in the London committee – she disagreed with John Stuart Mill and Harriet Taylor, who insisted that it was useful to have men on the committee – though she later served as its nominal secretary. For all his early support, Mill shrank back nervously from later developments and more aggressive tactics; he disapproved, particularly, of the ‘common vulgar motives and tactics’ of some women in Manchester. And the campaign to win the vote was to prove more difficult, and much longer-drawn-out, than its early supporters could have predicted. The issue was debated in 72

parliament (and defeated) year after year, all through the 1870s.

One Tory remarked in 1871 that women – who were sensitive and emotional by nature – should be protected ‘from being forced into the hurly-burly of party politics’. Woman’s proper sphere was the home; her duty – and her deepest pleasure – to be a good wife, or sister, or daughter. Moreover, if women had much influence in parliament, it would lead to ‘hasty alliances with scheming neighbours, more class cries, permissive legislation, domestic perplexities and sentimental grievances’. The largest vote in favour of women’s enfranchisement came in 1873, with 157 men in agreement.

Fightin

Suffrage abroad

g for th

At the same time, British suffragists (and their opponents)

e v

watched developments abroad with interest. One woman

ote

remarked that ‘scarcely anything does more good to wom-

: su

ffr

en’s suffrage in England than seeing those who speak from

agists

personal experience’. In fact, Antipodean examples seemed

particularly encouraging. In New Zealand, women could

vote from 1893; in Australia, state after state granted

women the vote during the 1890s, until in 1902 women

could finally vote in Federal elections. A conservative

(male) professor remarked, darkly, in 1904, that ‘I think

Australia is doomed’. (On the other hand, Australian

Aboriginals, male or female, could not vote until the late

1960s.) In America, the states, one by one, enfranchised

white women; by 1914, women could vote in 11 states,

though they had to wait until 1919 for the national vote.

Denmark enfranchised women in 1915, and the Netherlands

in 1919.

73

It is hardly surprising, given contemporary beliefs about a woman’s role, that, for decades, suffragists achieved only small and undramatic victories, though, in the long run, these would prove very important in winning over public opinion. But, in the face of rejection and ridicule, they persisted. At the same time, many women were gaining experience and confidence by taking increasingly active roles in local government and other public bodies; they served on school boards and poor-law boards. And they were learning to speak in public; as the suffragist Lady Amberley once remarked, ‘people expressed surprise to me afterwards to see that a woman could lecture and still look like a lady’. Moreover, the campaigning women emerged from every political persuasion, with Conservatives like Frances Power Cobbe and Emily Davies as committed to the cause as Liberal and Radical women.

By the 1890s, as a growing number of men were enfranchised, women’s sense of disparity and injustice increased sharply. They pointed out that men who were poor and barely literate had been

minism

given the vote, while well-educated women, who paid rates and

Fe

taxes, were still excluded from full citizenship. It has been argued that 1897 saw a real breakthrough: a bill in the House of Commons received a majority of 71 in favour of women, and the pattern was repeated in following years. None of this was translated into actual reform, but suffragists certainly felt encouraged.

74

The term ‘suffragette’ was coined in 1906 by the

Daily Mail

; it was a derogatory label that the growing militant movement adopted as their own and transformed. It was only very gradually that some suffragists, at least, had come to realize that they were achieving very little by peaceful means. But as early as 1868, Lydia Becker had claimed, dramatically but with some insight, that ‘it

needs

deeds of bloodshed or violence’ before the government can be ‘roused to do justice’.

By the early 1870s, a few women were taking the idea of ‘no taxation without representation’ literally, and refusing to pay. But there was little real change until 1903, when the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) was founded by the Pankhurst family. They had already been protesting actively in their native Manchester against attempts to ban meetings held by the Independent Labour Party.

Dr Pankhurst had in 1870 drafted the first Women’s Disabilities Removal Bill, which was then presented to parliament by Jacob Bright. (It passed on a second reading, but was quashed by William Gladstone.) Mrs Emmeline Pankhurst had served as a Poor Law Guardian, and had remarked that ‘though I had been a suffragist before I now began to think about the vote in women’s hands not only as a right, but as a desperate necessity’. Her daughter Christabel had probably been influenced, not only by her parents but by listening to, and writing a profile of, the American suffragist 75

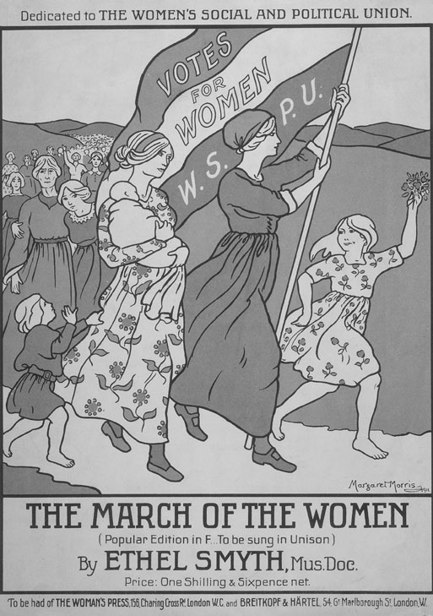

5. The cover of Ethel Smyth’s 1911 song-sheet for the WSPU proclaims

‘The March of the Women’ towards the vote. She uses the suffragette

colours – green, purple, and white – but this is a celebration, as much as

a demonstration, full of hope for a better future.