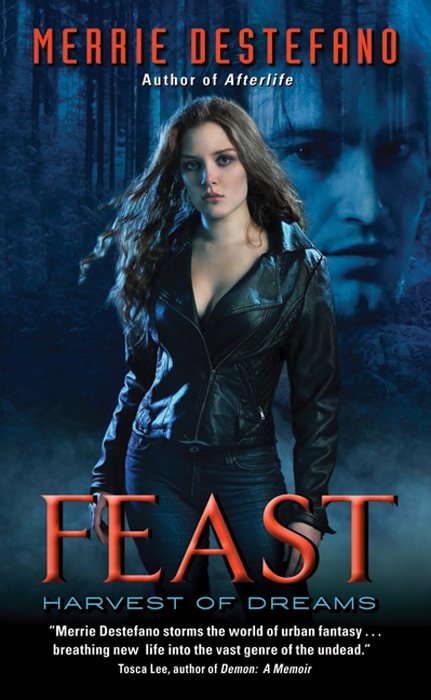

Feast

Authors: Merrie Destefano

FEAST

HARVEST OF DREAMS

MERRIE DESTEFANO

For my son, Jesse

Contents

Dream no small dreams for they have

no power to move the hearts of men.

—Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Ash:

She was just a girl—bony, pale-skinned and wild—when we stumbled upon each other in the woods, the wind shimmering through the trees around us. She was nothing like her parents, both of them sleeping back in their rented cabin, the stench of rum and coke seeping out the windows and doors.

She should have been scared when she saw me, appearing suddenly in the russet shadows, but I could tell that she wasn’t. Her long dark hair hung in a tangle, almost hiding her face. In that moment, I realized that she lived in a world of her own.

Just like me.

“Do you work at the inn?” she asked, her gaze running over my form curiously.

I nodded. Somehow she had recognized me. True enough, we’d seen each other often. I did work at the inn, and I brought her parents fresh linens and coffee every morning. But this was my free time and I no longer wore human skin.

“You’re different. Not like the other one.”

I frowned, unsure what she meant. I cocked my head and then followed her pointing finger with my gaze. She gestured toward a trail that led deep into the woods, all the way to the edge of my territory.

“Have you gone that way?” I asked, concerned when I saw her yawn.

She nodded and stretched, all of her barely as tall as my chest.

I heard him then, one of my wild cousins, calling to her. She lifted her head and listened.

“He wants me to come back.” She shifted away from me, started to head down a path that led to shadows and darkness. In that instant, a stray beam of sunlight sliced through the trees, fell upon her milky skin and set it aglow, almost like fire. That was when I saw them.

She was surrounded by imaginary playmates. Transparent as ghosts, an arm here, a leg there, a laugh that echoed and followed after her.

I quickly glanced at her forearms, bare for midsummer, and they bore no mark. No one had claimed her yet. She was still free.

I could have claimed her for myself right then and to this day I sometimes wonder why I didn’t. But she was so small—only seven years old, much too young to harvest, though my wild cousin wouldn’t think so.

His calls were growing more plaintive, more insistent; the trees began to moan beneath his magic, and I grew angry that he would consider intruding on my land with his wanton hunt.

She walked away from me then, and without thinking, I followed her, just like one of her imaginary playmates. They jostled alongside me, all of us watching her, hoping for a moment of her attention.

The trees parted to reveal a wide grove up ahead of us, filled with thimbleberry and wild peony, their fragrance drifting toward us, intoxicating as incense. I saw him then, right there at the edge of my territory, the land that I had claimed nearly a century earlier with my own terrible curse. He was one of the barbarians who regularly raided the other mountain villages and he stood akimbo, his dark skin glistening in the dappled light, his wings spread broad and proud.

She gasped and stopped walking.

He must have disguised himself when she’d seen him earlier. Pretended to be a woodland creature, a fox or a squirrel. But now he had grown confident in his spell over her, bold enough to expose himself for what he truly was—a dangerous predator daring to steal from me.

She glanced back toward me and whispered, “He looks like an angel, don’t you think?”

What did she think I looked like? I wondered.

“He’s beautiful,” she said.

“No, he’s not.”

Even from this distance, I could see his brutish features, the flattened nose and splayed legs, the long fingers with broken claws and the yellow teeth. His stench carried on the wind, unwashed flesh and carrion blood. Centuries of poor breeding had spawned beasts like this and I could see that he was near as old as I was, probably near as strong too. His eyes began to glow, pits of bright fire in the shadowed glen, and he lifted his chin, in both defiance and melody. A song drifted from his lips, sweet as clover honey; the chanted poetry began to wrap itself around the girl like ropes of silk. With just this tiny sliver of magic, the creature had her under his spell.

Her eyes fluttered and her limbs waxed soft and supple, her knees began to bend beneath her. I grinned wide when she fell to the ground, asleep and safe.

For she was still on my land.

The fool hadn’t known that you must tempt children nearer before you begin to sing, for the magic of home is too strong for them, a fact I knew all too well. That was how my own curse began, nigh on a century ago—by breaking all the laws.

“Give her to me,” my cousin growled, a fierce expression folding his face. His shape wavered when the sunlight grew stronger, passing from behind a bank of thick summer clouds. His naked skin sizzled and he drew away from me into the shadows. “She is

my

spoil. ’Twas my enchantment!”

“No. And you know it well. All that which lies within my boundaries is mine and mine alone.”

“ ’Twasn’t always that way, though,” he teased, trying to draw me out to battle. “Time was your mate shared this land with you, until you killed her.”

My blood turned to venom. I left the child on the ground and stepped nearer the forest’s edge. With one hand I reached through sun and shade until I gripped him by the throat and squeezed. I had been wrong, he wasn’t nearly as old or as strong as I was.

“You are wrong,” I said through gritted teeth, “though I thank you for reminding me.”

Both of my hands were about his throat then, tightening, driving the life from his ragged carcass as he flailed and clawed. I held him, breathless as if he had plunged beneath a pool of icy water, watched his strength fail, all the while enjoying his torment, until I heard the child moan behind me.

She was waking up.

“Begone, foul beast,” I said in lowered tones. “Leave and never return or I promise you, I will finish what we have begun on this day. And you will cross over into the Land of Nightmares, never to return.” I released him and he fell to the ground like a sack of dead rabbits, loose and unmoving. Only his eyes glaring up at me and the shallow movement of his chest proved that life still flowed through his bones.

I turned my back on him, shifting my skin at the same time, assuming the familiar features of Mr. Ash, caretaker of the nearby inn and groundskeeper of the forest. I sang my own soft enchantment as the child opened her eyes, changing her memories just a bit so she’d forget about the wild creatures she had seen here today.

She wiped a hand across her forehead and yawned.

“Miss MacFaddin,” I said, a tone of surprise in my voice. “Have you taken a nap in the woods?” I reached a hand down to draw her to her feet.

She nodded as she looked around us both, a bit confused.

“I did,” she answered, her brow furrowed as if she didn’t believe her own words.

Some enchantments take instantly. Others take days. Eventually, she would forget that she had seen me in my true shape.

“Let me walk you back to your cabin and safety, young lady,” I said, putting one hand ever so gently upon her shoulder.

She glanced up at me through that wild tangle of dark hair, her eyes filled with mystery and curiosity and something that I don’t see very often. Gratitude. Some part of her still remembered what she had seen, I realized, and that thought made me strangely glad.

We parted at the forest’s edge, her cabin in sight. She turned at the halfway mark, when she was fully surrounded by green meadow; she waved at me and smiled. I saw her imaginary friends gather about her, only this time I could see who and what they were.

A cowboy, a princess, a faery, all pale as ghosts.

And another shadowy creature, new to the pack, stood away from the others, wings folded neatly at his back.

This last creature was me.