Fathermothergod: My Journey Out of Christian Science (11 page)

Read Fathermothergod: My Journey Out of Christian Science Online

Authors: Lucia Greenhouse

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Religion, #Christianity, #Christian Science, #Religious

I make it to twenty-five minutes.

“Da-ad!” I yell sort of weakly, suggesting great pain.

He comes in right away.

“It’s not getting … better,” I moan.

Together we recite the Scientific Statement of Being: “There is no life, truth, intelligence, nor substance in matter …”

And then the Beatitudes: “Blessed are the meek: for they shall inherit the earth …”

Somehow, I don’t think this is what Jesus had in mind. I know that what I’m doing is wrong. It’s hard to believe my father is falling for it. But I can’t dwell on it too much while he’s in the room with me, or I might crack a smile. Instead, I shiver again, just slightly, and ask if he wouldn’t mind closing the window.

This is an incredible waste of time, lying in my parents’ bed all afternoon, when I know I have to study for my tests. I get up twice to “try” to use the loo, semi-buckled over, wrapped in Sherman’s comforter.

I hear the front door open downstairs and realize that Mom has come home early. When I hear my parents whispering in Dad’s study, I start to feel guilty. Dad is worried enough that he called Mom home. The initial giddiness and subsequent boredom of my ruse have vanished. Now there’s a fleeting but not altogether unpleasant surprise at their concern, which is quickly replaced by the visceral fear of being found out.

My parents’ room is very warm. The radiator hisses because earlier I told Dad I was

freezing

and asked him to open the valve. Now I am roasting. When Mom comes in and feels my forehead, it is totally sweaty. She asks if I’d like something to eat, chicken broth or buttered toast. The buttered toast sounds delicious—I’m starving—but I say no, I’m nauseous, so I don’t blow my cover.

I wonder if Mom offers chicken broth and buttered toast to Hawthorne House’s guests, or patients, or clients—or whatever they call them. Does she press a cool, damp cloth to someone’s feverish forehead? Wouldn’t that gesture of kindness—an acknowledgment of the existence of fever—be forbidden?

After another hour, it is time to execute a beautiful, gradual healing. It takes about forty-five minutes, two full intervals of my parents’ checking in on me. I time it perfectly so that I can miss my train, stay the night, and delay returning to Claremont. Mom lets me sleep in and study for my tests in the morning, and makes me Swedish pancakes, before riding the train with me all the way back to Claremont.

G

OD

. The great I

AM;

the all-knowing, all-seeing, all-acting, all-wise, all-loving, and eternal; Principle; Mind; Soul; Spirit; Life; Truth; Love; all substance; intelligence

.

—M

ARY

B

AKER

E

DDY

,

Science and Health

, Glossary

C

LAREMONT

S

CHOOL

P

ASSING

O

N

Susie and I

are in the dorm; everyone else has gone down to dinner. I am changing out of my school uniform, and she is lolling on her bed next to mine. The bell announcing dinner rang almost ten minutes ago. Susie will miss the headmistress’s grace, and her penalty may be kitchen duty, but she doesn’t care. She’s more of a rule breaker than I am. During Quiet Time in the morning, when we are supposed to be reading a section of the Bible Lesson, she fills out magazine questionnaires about personality type, carnal knowledge, and boyfriends, which she keeps folded up in the pages of her

Science and Health

. On Saturday afternoons, when we walk along Esher High Street, she wears thick black Mary Quant eyeliner and tight jeans and smokes cigarettes with equanimity, while I am nervously on the lookout for teachers.

“What’s the occasion?” she asks, and I shrug my shoulders, but I’m not feeling as casual as the gesture implies.

Mrs. Williams found me this afternoon in the library to say that Mum was coming to take me out for dinner, which is odd. It’s a school night. And it’s not my birthday—not that

that

would justify special dispensation at Claremont; Mary Baker Eddy says, “Man in Science is neither young nor old. He has neither birth nor death,” so birthdays are downplayed. What is most unsettling is the fact that Mrs. Williams didn’t say anything about Dad coming. Mom and Dad never come to see me separately. And they never visit without a clear purpose.

I wait alone in the marble entrance hall, and my mind keeps returning to the reason for Mom’s visit. As I sit on my hands on the windowsill, I assume nothing good.

It’s Dad. Maybe he’s sick. Or maybe they’re getting divorced

. It’s hard to picture either possibility, because I never see Mom and Dad fighting, and Dad never gets sick.

Of course, I hardly see them, period, so how would I know? Maybe he

is

sick.

Then, I correct myself:

Am I going to allow mortal mind to whisper to me of evil?

I think of a passage in

Science and Health:

“When the illusion of sickness or sin tempts you, cling steadfastly to God and His idea.”

I tell myself that in God’s kingdom, there can be no disease (dis-ease). There is only perfection.

Right at six-thirty, Mom drives up in her Volkswagen Golf, and when I descend the school’s majestic front steps, she is out of the car, enveloping me with a big hug. Her embrace feels like a warning, but it reveals nothing right away. Our conversation during the short drive to the restaurant is nonspecific. Over fish and chips at the pub, Mom asks me about school, and whether the girls in our dorm are getting along better. She says that Dad’s sorry he couldn’t come; he’s working. Sherman won his rugby match yesterday. Olivia called the other day and likes Sarah Lawrence College. Whenever there is a lull in the conversation, Mom fills the void with a question about my studies.

For dessert, we order trifle, with two spoons, and after a few bites, she puts her spoon down.

“There is something I need to tell you.”

My stomach knots up. Worry is all over her face.

“Aunt Mary called this morning.”

As my mother struggles to find the words for whatever it is she must tell me, my mind races ahead:

Something’s happened to Grandma, or Aunt Kay, or one of my uncles. Or Grandpa or Ammie

.

“It’s about your friend James,” she says softly.

For some reason, before my mother utters another word, my face flushes with emotion. I don’t know if it’s fear, anger, dread, or betrayal. My mother is on the verge of tears.

“I—he—” Mom attempts, looking down in her lap and then again up at me. “Aunt Mary called to tell me that—he—is dead.” Mom shakes her head, correcting herself. “He’s passed on, Lucia.”

“What?”

I shake my head. James is fifteen, like me.

I have letters from him. I see the handwriting—the

young

handwriting and misspelled words—of the cards he has sent me. I still picture him twelve, the age we were when we first met, when he pulled me back, back, back on the tire swing, and let go.

Lowering her voice, my mother says that he has taken his own life.

I cannot breathe.

I feel like I’ve been pinned against the back of the booth.

Mom reaches for my hand, but I pull it back.

“What?” I say. I am angry. I am confused.

We sit there in silence.

“What?” I say again.

The pub feels too small, the wood-paneled walls too close. Mom says nothing. I want information, but she gives me none. She can’t—or won’t—bring herself to tell me anything more.

“Lucia, what we have to remember,” she finally says, now grabbing my hand against my will, “and really hold on to, is what Mary Baker Eddy tells us about death: ‘The belief in sin and death is destroyed by the law of God, which is the law of Life instead of death, of harmony instead of discord, of Spirit instead of the flesh.’ ”

Mom drops me

off after dinner, and Susie is waiting for me. She can see that I have been crying, but when she asks me what’s wrong, what happened at dinner with Mum, I don’t feel sadness, or grief. I feel nothing, as in no sensation. In my mind, I hear,

there is no sensation in matter

, and I know it’s from

Science and Health

and/or Sunday school. Monotone, I tell Susie that James killed himself. Her eyes grow wide and her face turns white, and all of a sudden she is sobbing, and clutching me, horrified, and I’m hugging her back, but everything seems strangely backward.

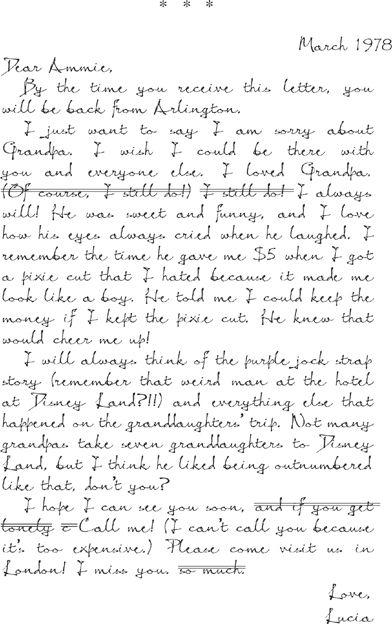

It is eleven-thirty at night. I’m down the hall in the Quiet Room, because I can’t sleep. I’m uneasy about what I should say in this condolence letter, but I think what I wrote probably turned out okay. I take the Liquid Paper from my pencil box and dab the crossed-out words until they disappear. I crossed out “so much” because I don’t want Ammie to worry about me. And I crossed out “and if you get lonely” because mentioning it might make her feel even worse. She and Grandpa were married for forty years, and now she’ll be alone.

I fold the aerogram into thirds, then lick the adhesive edges and seal it up. I write Ammie’s name and address on the front. I have to remind myself not to write “Gen. and Mrs. H. Terry Morrison.” That Grandpa could be—is—dead doesn’t seem possible.

The last time I saw Grandpa was three months ago, when we flew to Minnesota for Christmas. (But first we visited boarding schools on the East Coast because, at the end of this year, we are moving. Another of Mom and Dad’s classic out-of-the-blue announcements. They said we were “moving back,” and I brightened for about a millisecond, imagining a return to our old house, our old life. But we are moving to New Jersey.

New Jersey?

)

We were at Ammie and Grandpa’s for Christmas dinner. After the meal Grandpa tried to get up and sort of stumbled, and reached for the sideboard to steady himself. I thought he was going to fall down, but Ammie was right there beside him. I didn’t know he was sick (Mom and Dad never told me), but I remember feeling scared that something bigger was going on than just a misstep.

Last night Mom and Dad called me from Hampstead to say that Grandpa had passed on, and they were flying to Minnesota and would be back in a week. Dad told me I shouldn’t be sad:

Grandpa’s passing wasn’t unexpected. He lived a happy, long life

.

But it was unexpected for me! I didn’t even really know he was sick. I only found out that Grandpa wasn’t well because Ammie mentioned it in a letter. And I

am

sad. How could I not be? I’ll never see him again.

Mostly, I’m angry that I can’t go back for the funeral. Mom and Dad said it’s too expensive, and Sherman and I would miss too much school. But

they’re

going. It’s not our fault we live here, so far away; it’s

theirs

. They should bring us. The other grandchildren—all twenty-one of them—are going to be at the service, and then everyone is flying to Washington, D.C., for the burial at Arlington cemetery.

First James. Now Grandpa.

Dad reminded me what Mary Baker Eddy said about death: “ ‘Death is but a mortal illusion, for to the real man and the real universe there is no death-process.’ ”

In some ways, death

does

feel like an illusion. From here, being so far away, it’s easy to think that James and Grandpa are still alive. Even the letters from Mimi and Mary, which described James’s memorial service, seem unreal. They are not the letters I choose to reread. James’s are.

I don’t know how Sherman’s taking the news about Grandpa. I haven’t talked to him, and I won’t see him until Sunday school. I can’t call him because I don’t have coins for the pay phone, and I can’t reverse the charges like I do when I call Mom and Dad. Either Sherman is feeling really lonely or else he’s not feeling much at all. Like me.

* * *

One Tuesday morning

, my roommates and I head down to the common room for Quiet Time like we always do before school, to find that Mr. and Mrs. Williams’s door is closed. The door to their quarters is always open, except on their day off, which is Monday. Mrs. Williams always proctors Quiet Time, but today, the matron, Mrs. Mills, does.

“Where’s Mrs. Williams?” we all ask. “Why is their door closed?”

Mrs. Mills looks up from her

Science and Health

, then down at her plump hands. She purses her lips and in her Welsh accent says that the Williamses are taking a brief leave.

“Why?” we ask. “Where are they going?”

“They’re not going anywhere. But we ought to be mindful of their needs. And respectful of their privacy. We should try to keep the noise to a minimum.”

We all look at one another, puzzled.

Over the next few days, the Williamses’ door remains shut, and rumors fly. Mrs. Williams is sick. Mr. Williams is sick. Their daughter who lives in Australia is sick. They’ve been terminated.