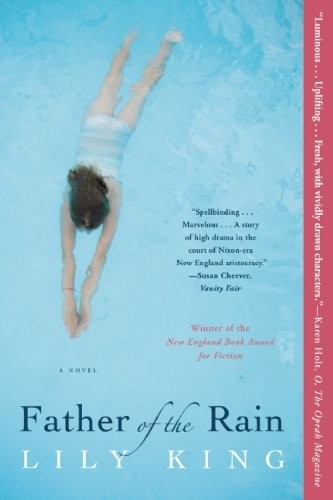

Father of the Rain

Read Father of the Rain Online

Authors: Lily King

Father of the Rain

Also by Lily King

The Pleasing Hour

The English Teacher

Lily King

Copyright © 2010 by Lily King

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003 or [email protected].

My deepest gratitude to my husband and very first reader, Tyler Clements, and to Susan Conley, Sara Corbett, Caitlin Gutheil, Anja Hanson, Debra Spark, Liza Bakewell, Wendy Weil, Deb Seager, Morgan Entrekin, Eric Price, Jessica Monahan, Lisa King, Apple King, and my mother; and to my beloved daughters, who put up with all this. A special, devotional thank you to my extraordinary editor, Elisabeth Schmitz.

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN-13: 978-0-8021-9708-5 (e-book)

Atlantic Monthly Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Distributed by Publishers Group West

www.groveatlantic.com

For Lisa and Apple

Hath the rain a father? or who hath begotten the drops of dew?

—The Book of Job, 38:28

Father of the Rain

My father is singing.

High above Cayuga’s waters, there’s an awful smell.

Some say it’s Cayuga’s waters, some say it’s Cornell

.

He always sings in the car. He has a low voice scraped out by cigarettes and all the yelling he does. His big pointy Adam’s apple bobs up and down, turning the tanned skin white wherever it moves.

He reaches over to the puppy in my lap. “You’s a good little rascal. Yes you is,” he says in his dog voice, a happy, hopeful voice he doesn’t use much on people.

The puppy was a surprise for my eleventh birthday, which was yesterday. I chose the ugliest one in the shop. My father and the owner tried to tempt me with the full-breed Newfoundlands, scooping up the silky black sacks of fur and pressing their big heavy heads against my cheek. But I held fast. A dog like that would make leaving even harder. I pushed them away and pointed to the twenty-five dollar wire-haired mutt that had been in the corner cage since winter.

My father dropped the last Newfoundland back in its bed of shavings. “Well, it’s her birthday,” he said slowly, with all the bitterness of a boy whose birthday it was not.

He didn’t speak to me again until we got into the car. Then, before he started the engine, he touched the dog for the first time, pressing its ungainly ears flat to its head. “I’m not saying you’s not ugly because you

is

ugly. But you’s a keeper.

“From the halls of Montezuma,” he sings out to the granite boulders that line the highway home, “to the shores of Tripoli!”

We have both forgotten about Project Genesis. The blue van is in our driveway, blocking my father’s path into the garage.

“Jesus, Mary, and Joseph,” he says in his fake crying voice, banging his forehead on the steering wheel. “Why me?” He turns slightly to make sure I’m laughing, then moans again. “Why me?”

We hear them before we see them, shrieks and thuds and slaps, a girl hollering “William! William!” over and over, nearly all of them screaming, “Watch me! Watch this!”

“I’s you new neighba,” my father says to me, but not in his happy dog voice.

I carry the puppy and my father follows with the bed, bowls, and food. My pool is unrecognizable. There are choppy waves, like way out on the ocean, with whitecaps. The cement squares along its edge, which are usually hot and dry and sizzle when you lay your wet stomach on them, are soaked from all the water washing over the sides.

It’s my pool because my father had it built for me. On the morning of my fifth birthday he took me to our club to go swimming. Just as I put my feet on the first wide step of the shallow end and looked out toward the dark deep end and the thick blue and red lines painted on the bottom, the lifeguard hollered from his perch that there were still fifteen minutes left of adult swim. My father, who’d belonged to the club for twenty years, who ran and won all the tennis tournaments, explained that it was his daughter’s birthday.

The boy, Thomas Novak, shook his head. “I’m sorry, Mr. Amory,” he called down. “She’ll have to wait fifteen minutes like everyone else.”

My father laughed his you’re a moron laugh. “But there’s no one in the pool!”

“I’m sorry. It’s the rules.”

“You know what?” my father said, his neck blotching purple, “I’m going home and building my own pool.”

He spent that afternoon on the telephone, yellow pages and a pad of paper on his lap, talking to contractors and writing down numbers. As I lay in bed that night, I could hear him in the den with my mother. “It’s the rules,” he mimicked in a baby voice, saying over and over that a kid like that would never be allowed through the club’s gates if he didn’t work there, imitating his mother’s “Hiya” down at the drugstore where she worked. In the next few weeks, trees were sawed down and a huge hole dug, cemented, painted, and filled with water. A little house went up beside it with changing rooms, a machine room, and a bathroom with a sign my father hung on the door that read

WE DON’T SWIM IN YOUR TOILET—PLEASE DON’T PEE IN OUR POOL

.

My mother, in a pink shift and big sunglasses, waves me over to where she’s sitting on the grass with her friend Bob Wuzzy, who runs Project Genesis. But I hold up the puppy and keep moving toward the house. I’m angry at her. Because of her I can’t have a Newfoundland.

“Fuzzy Wuzzy was a bear,” my father says as he sets down his load on the kitchen counter. “Fuzzy Wuzzy had no hair.” He looks out the window at the pool. “Fuzzy Wuzzy wasn’t fuzzy, was he?”

My father hates all my mother’s friends.

Charlie, Ajax, and Elsie smell the new dog immediately. They circle around us, tails thwapping, and my father shoos them out into the dining room and shuts the door. Then he hurries across the kitchen in a playful goose step to the living room door and shuts that just before the dogs have made the loop around. They scratch and whine, then settle against the other side of the door. I put the puppy down on the linoleum. He scrabbles then bolts to a small place between the refrigerator and the wall. It’s a warm spot. I used to hide there and play Harriet the Spy when I could fit. His fur sticks out like quills and his skin is rippling in fear.

“Poor little fellow.” My father squats beside the fridge, his long legs rising up on either side of him like a frog’s, his knees sharp and bony through his khakis. “It’s okay, little guy. It’s okay.” He turns to me. “What should we call him?”

The shaking dog in the corner makes what I agreed to with my mother real in a way nothing else has. Gone, I think. Call him Gone.

Three days ago my mother told me she was going to go live with my grandparents in New Hampshire for the summer. We were standing in our nightgowns in her bathroom. My father had just left for work. Her face was shiny from Moondrops, the lotion she put on every morning and night. “I’d like you to come with me,” she said.

“But what about sailing classes and art camp?” I was signed up for all sorts of things that began next week.

“You can take sailing lessons there. They live on a lake.”

“But not with Mallory and Patrick.”

She pressed her lips together, and her eyes, which were brown and round and nothing like my father’s yellow-green slits, brimmed with tears, and I said yes, I’d go with her.

My father reaches in and pulls the puppy out. “We’ll wait and see what you’s like before we gives you a name. How’s that?” The puppy burrows between his neck and shoulder, licking and sniffing, and my father laughs his high-pitched being-tickled laugh and I wish he knew everything that was going to happen.

I set up the bed by the door and the two bowls beside it. I fill one bowl with water and leave the other empty because my father feeds all the dogs at the same time, five o’clock, just before his first drink.

I go upstairs and get on a bathing suit. From my brother’s window I see my mother and Bob Wuzzy, in chairs now, sipping iced tea with fat lemon rounds and stalks of mint shoved in the glasses, and the kids splashing, pushing, dunking—the kind of play my

mother doesn’t normally allow in the pool. Some are doing crazy jumps off the diving board, not cannonballs or jackknives but wild spazzy poses and then freezing midair just before they fall, like in the cartoons when someone runs off a cliff and keeps moving until he looks down. The older kids do this over and over, tell these jokes with their bodies to the others down below, who are laughing so hard it looks like they’re drowning. When they get out of the pool and run back to the diving board, the water shimmers on their skin, which looks so smooth, like it’s been polished with lemon Pledge. None of them are close to being “black.” They are all different shades of brown. I wonder if they hate being called the wrong color. I noticed this last year, too. “They like being called black,” my father told me in a Fat Albert accent. “Don’t you start callin’ ‘em brown. Brown’s down. Black’s where it’s at.”

The grass feels good on my feet, thick and scratchy. I put my towel on the chair beside my mother.

“You heard Sonia’s group lost its funding,” Bob was saying. I don’t know if Bob Wuzzy is white or black. He has no hair, not a single strand, and caramel-colored skin. When I asked my mother she asked me why it mattered, and when I asked my father he said if he wasn’t black he should be.

“No,” my mother says gravely, “I didn’t.”

“Kevin must have pulled the plug.”

“Jackass,” my mother says; then, brightening up, “How’s Maria Tendillo?” She pronounces the name with a good accent that my father makes fun of sometimes.

“Released last Friday. No charges.”

“Gary’s the best.” My mother smiles. Then she lifts her face to mine.

“Hello, Mr. Wuzzy,” I say, and put out my hand.

He stands and shakes it. His hand is cold and damp from the iced tea. “How are you, Daley?”

“Fine, thank you.”

They exchange a look about my manners and my mother is pleased. “Hop in, honey,” she says.

This morning she told me I was old enough now to host Project Genesis with her, that all the kids would be roughly my age and I could be an envoy to new lands and begin to heal the wounds. I had no idea what she was talking about. Finally she said I should just be nice and make them feel welcome and included.

“How can I make them feel included when there is only one of me and so many of them?”

I knew she didn’t like that answer, but because she was worried I’d tell my father we were leaving, she asked me softly if I could just promise to swim with them.

I stand on the first step, my feet pale and magnified by the water. I feel my mother willing me to behave differently, but I can’t. I can’t leap into the fray like that. It isn’t in my nature to assume people want me around. All I can do is watch with a pleasant expression on my face. The older kids are still twisting off the diving board. The younger ones are here in the shallow end, treading water more than swimming, their faces flush to the surface like lily pads. In the corner two girls are having underwater conversations. A boy in a maroon bathing suit slithers through them and they both come up screaming at him, even though he is underwater again and can’t hear. There are four boys and three girls, all different sizes, and I wonder if some of them are siblings. They seem like it, the way they yell at each other. But no one gets mad or ends up crying like I always do.

I move slowly from one step to the next, then walk out on tippy toes. They aren’t looking at me, but they all pull away as I approach. At the slope to the deep end, my feet slip and I go under. It’s cool and quiet below until a body drops in, a sack of bubbles. Normally when I look up from the bottom of the pool, the surface

is only slightly buckled, like the windowpanes in the attic, but now it’s a white froth. The boy in the maroon bathing suit passes right above me. His toes brush through my hair and he screams.