Fatal Storm (32 page)

Authors: Rob Mundle

Lachlan Murdoch was equally contemplative. “I think a lot of the guys in this crew have very strong mixed feelings about even finishing in this race at all. You needed to be out there to know just how bad it was. If you imagine any disaster movie you have seen before you have to double it or treble it.”

Navigator Mark Rudiger, winner of the previous Whitbread round-the-world race with the team led by American Paul Cayard echoed the sentiments expressed by Murdoch. “The Sydney to Hobart lived up to all the fears I ever held about this race and then some. I was hoping I’d get away with an easy one but I didn’t. At times it was worse than the Whitbread. It didn’t last as long, fortunately, but at its peak the wind and waves we saw coming across Bass Strait were the worst that I have ever encountered.”

New Zealander Chris Dickson has done very little ocean racing since the ‘98 Hobart. Instead, he has concentrated much of his time on campaigning for the America’s Cup, and being a family man. “I certainly haven’t done another Hobart race, and I don’t plan to. I still hold some very clear and vivid memories of it, and that’s enough for me.

“Ten years down the track my priorities have changed. I have a wife and two little girls, aged six and eight, and they are my life. However, my wife does still remind me that we’d been married for just a week when the race finished, and that I’d taken her to Hobart for a honeymoon – which it wasn’t. She insists she’s still waiting for the real one!”

For Dickson the race was the most powerful reminder of what sailors know, but many won’t accept. “It was a reminder that ocean racing is a dangerous activity. Walking across the road can be a dangerous activity; people die climbing Mount Everest; and people die ocean racing. When I was single and making a living from going ocean racing as a professional I never thought twice about the dangers. But now, as a married professional sailor, I don’t want to go ocean racing. As a dad with two young kids, it would now be selfish for me to even think about taking that risk, even though it is a measurable risk.

“Also, after that Hobart there was another emotional burden that was lingering in my mind. I scared myself with the thought that was generated by the fact that I was then a married man, and would inevitably become a father; I dreaded the thought of turning up at the end of an ocean race as the skipper of a yacht and having to try to explain to someone’s wife, or child, why I didn’t bring their dad back. That’s a thought I’ve had with me since that Hobart. I now see it as being a selfish activity to be pursuing when others depend on you.

“Additionally, that Hobart race was very much a reminder that once you are out there you are on your own. The ‘98 race was fortunate in that there was such an incredible response from search and rescue organisations, and because most of those who were in trouble could be helped because they were relatively close to shore and just in range of helicopter assistance. It could have been a lot worse.

“Most ocean races are a bit like climbing Everest: you put yourself there, you’re on your own, and you know it. It means that everything comes down to preparation. I again realised after the Hobart that your life depends on your preparation, which in many ways is the team of people you have with you, and then there’s the integrity of your boat. So it’s your boat and how you handle it, because if your boat stays afloat you’re going to be OK – things can get pretty ugly, but you’re going to be OK. If your boat doesn’t stay in one piece, it’s a bit like your equipment failing when you are climbing Mount Everest: it means there’s a good chance you’re going to die. That’s not an ‘if’ or a ‘maybe’ – the odds are that you will die. We all know this is real because we’ve seen enough footage of people on Everest who know they’re going to die.

“In ocean racing, if you haven’t done your preparation you are in trouble before you leave the dock. You must prepare the boat meticulously, check the equipment, dot the i’s and cross the t’s; and if you haven’t been 100 per cent thorough before you leave the dock then you’re putting everyone’s life at risk, including your own.

“The other lesson for us aboard

Sayonara

was that the damage that we did to boat and people came as a result of us not backing off the pace soon enough, not changing down a gear by making a change from a big sail to a smaller one and reduce speed before it was too late.

To do such a sail change inside a harbour might take 10 minutes on a big maxi-boat like this one, but doing that same manoeuvre in the middle of Bass Strait on a pitch black night, when it’s blowing 50 knots and waves are breaking over the boat, and with crew members who are shattered because they have been working their hearts out for two days solid, or are below deck and incapacitated, then that same manoeuvre might take you an hour – and it’s a lot more dangerous.

“So, the second of those big lessons is that when things start looking a bit ugly then get the sail off early. For many racing sailors this is always a hard decision because it means you are deciding that safety and survival is then more important than racing. That’s a really hard mental shift to make because you’re racing, racing, racing. It’s a bit like you’re pregnant or you’re not! You’re racing or you’re not. Looking back at that Hobart, I’d have to say that maybe we would have made that decision earlier. I was never overly concerned at the time for the safety of our own boat, even though we had broken gear, structural delamination in the hull, and there were injured people below. The boat was incredibly well prepared, superbly built and exceptionally well maintained, and we had a crew of the best professional sailors in the world – so things were in our favour. Even so, in hindsight we probably should have come off the pace sooner.”

Hobart and heartache

F

rom the time

Sayonara

arrived until the last yacht crossed the line at dusk on January 1, the normally boisterous dockside scenes in Hobart were replaced by a respectful silence. Most activity centred around all the major television networks who had descended on the city, bringing satellite dishes, broadcast vans and spotlights.

Brindabella

crossed the finish line almost three hours after

Sayonara

, followed by the battle-scarred remnants of what had been a strong 115-yacht fleet. With each arrival came incredible stories of survival, of unbridled courage, and of how fate had intervened. It was not until these crews got to the dock, saw family and friends and heard of the death and carnage in their wake, that they could completely comprehend the magnitude of events. One of the most remarkable achievements was that of David Pescud and his team of disabled sailors aboard

Aspect Computing.

As well as completing the course they were placed first in their race division. The motto for this crew was “Carpe Diem” – Seize The Day. Events in Bass Strait galvanised friendships, and there was none greater than that of two

Aspect Computing

crewmembers, the race’s youngest competitor, 12-year-old Travis Foley, a

dyslexic from Mudgee in NSW, and his blind crewmate, Mooloolaba’s Paul Borg.

The bond was apparent when the two went to the podium to join Pescud in collecting their prize for being first in PHS Division. Young Foley was Borg’s “eyes” onshore as they went forward to be saluted by the large dockside crowd. Borg already had 28-year-old Danny Kane to help him on the yacht over the previous 12 months. Kane was partially paralysed after suffering a stroke four years earlier. During the race Foley became part of that special team. “I was helping Paul whenever I could,” said young Foley, “showing him where things were and helping him get into his wet weather gear. This whole crew are now my best friends.” Foley, who was doing his first ocean race admitted he was scared, but added he’d do it again.

At the other end of the spectrum was 81-year-old Papa Tom – Sir Thomas Davis – former Prime Minister of the Cook Islands. He was the champion among the crew of 26 aboard the 83-foot

Nokia.

Despite the horrors he’d faced and the protestations of his friends, Papa Tom was more than glad he accepted skipper David Witt’s invitation to join the yacht. His medical background had enabled him to assume the role of crew doctor and at the height of the storm he’d spent all his time below caring for the injured. He remarked he was by no means cured of ocean racing, but he was cured of the Sydney to Hobart.

The tragedies that had crushed the race also overshadowed an incredible achievement by the overall race winners, Sydney’s Ed Psaltis and Bob Thomas with their 35-footer,

AFR Midnight Rambler.

This relatively small and lightweight yacht was tenth into Hobart,

beating many larger yachts home. Declared the race winner on handicap,

Midnight Rambler

became the smallest yacht in a decade to take the major prize. It was Psaltis’ 17th attempt to win the classic, his previous best placing being eighth with the even smaller

Nuzulu

in 1991.

“If there was an element of luck then it was that we got the worst of the weather during the daylight hours,” he said. “We could see the most dangerous of the waves coming at us and because of that we had the best possible opportunity of getting the yacht over them. I guess you could say we didn’t get ‘that wave’, the really big one that wiped out so many others. If it had been dark it might have been a different story.”

On January 1, 1999, a large crowd, weighed down with sadness, watched in silence as six floral wreaths were cast onto the waters off Constitution Dock in Hobart in memory of those who would not race again.

S

ailing has always been my passion and since leaving school that passion has also become my career. The 1998 race was the 30th Sydney to Hobart that I covered. In that period I had also managed three starts and three finishes in the classic. Being in Hobart in 1998 to report on the finish for television and newspapers saw me stretched – like so many of the race competitors – to the absolute limit of my emotional capacity. Suddenly my sport and my life had come face to face with fatalities.

For me, being ashore and knowing from some tough sailing experiences just how horrendous things were in Bass Strait, then trying to relay that in a composed fashion to the world, was not a pleasant experience. People had already died and I knew more would. At the same time I was trying to cope with my own emotional burden. Friends were the subject of searches. Were they dead or alive?

Then there was the fielding of a flood of telephone calls from anxious wives and friends. I had to try to assure them that everything would be OK, that they should have faith. It was almost as tough as being in the race. Those people desperately needed to know if their husband, father, sister, son or brother was coming home.

To speak with Robyn Rynan on the telephone that third night and confirm for her that her young son Michael – who was aboard

Winston Churchill

– had been found alive in a liferaft was a bittersweet experience. I will never forget her torrent of tears, wavering voice and sobbing sighs of relief. It brought a realisation of what family bonds are all about. At the same time there was the thought of what other families – those that didn’t

know the fate of their loved-ones – must be going through.

Subsequent to this tragedy I have been regularly asked why we go ocean racing. For me one of the most appropriate answers is found in Sharon Green’s great book of her sailing photographs,

Ultimate Sailing.

“It is a romantic sport…not carried out against the elements, but because of them.“

Sydney to Hobart race headquarters – the Cruising Yacht Club of Australia (CYC) on the shores of Sydney Harbour. The outside deck is the favourite spot for pre-race festivities.

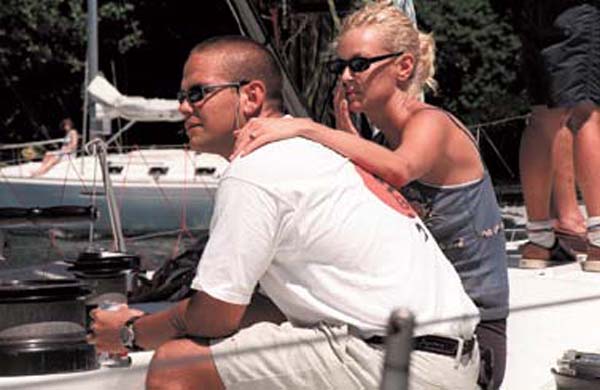

High profile crewmember Lachlan Murdoch and then wife-to-be Sarah O’Hare relax on the deck of

Sayonara

at the dock just hours before the start. There is always an air of anticipation hanging over the fleet at this time.

Meticulous effort goes into the preparation of the hull and keel of a race yacht. The keel is moulded out of lead with most of its weight concentrated at the bottom.