Far Afield

Books by

Susanna Kaysen

Asa, As I Knew Him

Far Afield

Girl, Interrupted

Susanna Kaysen

Far Afield

Susanna Kaysen is also the author of the novel

Asa, As I Knew Him

, and

Girl, Interrupted

, a memoir.

She lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

I am grateful to the MacDowell Colony, Inc., and the Artists Foundation of Massachusetts for their generosity, and to Jay Wylie for starting me on this long journey.

This is a work of fiction. All characters are the product of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

VINTAGE CONTEMPORARIES EDITION, JUNE 1994

Copyright © 1990 by Susanna Kaysen

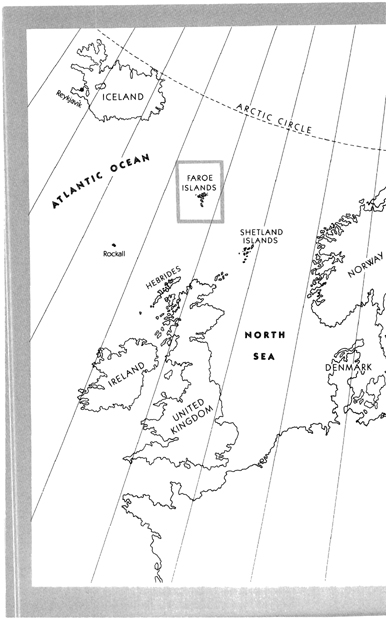

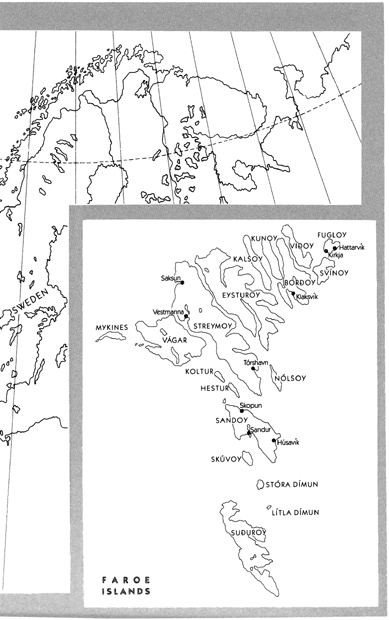

Map copyright © 1990 by Maura Fadden Rosenthal

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kaysen, Susanna, 1948–

Far afield / Susanna Kaysen.—1st ed.

p. cm.—(A Vintage contemporaries original)

eISBN: 978-0-8041-5107-8

I. Title.

PS3561.A893F37 1990 89-21538

813′.54—dc20

Author photograph © Marion Ettlinger

v3.1

For Annette and Carl

Contents

Cover

Other Books by This Author

About the Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Map

Transit

Jonathan was in the Reykjavik Airport with his passport and travelers’ checks in his jacket pocket, his Icelandair ticket with baggage claim checks attached in his shirt pocket, and no baggage at all.

“It’s in Copenhagen, sir,” the ticket clerk assured him. “We apologize, but in fact it happens quite normally.”

“Do you

know

it’s there?”

“Most certainly it is.” When Jonathan did not move away from the desk, the clerk said, “You wish it to be forwarded to your hotel?”

“When will it arrive?”

“Within a few days. Yes, certainly. By the end of the week.”

Jonathan’s shirt, which smelled of airplane, took on the tang of fresh sweat at this. “It won’t do,” he said. The clerk pretended not to understand. “I’m only staying overnight.”

“You are going to London? We can also forward to London.”

“No, to the Faroes.”

In the months before his departure from Cambridge, Jonathan had grown accustomed to the glaze that followed this announcement and had learned to be ready with latitude and longitude, brief history, population statistics, justifications—particularly these, which had been worn thin, to his ears, in conversations with the professors of the anthropology department. He did not expect that here, in the closest thing the archipelago had to a neighbor. And he was definitely unprepared for derision.

The clerk widened his ice-blue eyes. “The Faroes! People do not go there.” He issued a strange smile. “You are an ornithologist?” Jonathan shook his head. “There is nothing there,” said the clerk. To prove his point he turned his back on Jonathan.

“But you will forward there?” Jonathan noticed he was taking on the clerk’s lilting cadence. “Will you?”

“There is only one plane a week.”

“No, there are two.” This information had cost Jonathan forty dollars in transatlantic phone calls, and he was proud of it.

But Scandinavians do not like to be contradicted. “The next plane is on the following Tuesday,” the clerk said. “We can forward on that.”

It was Wednesday. His plane to the Faroes left Thursday afternoon from this airport; he had a ticket inside his passport. “Well, do that,” he said. “Forward on the plane next week.” He wrote his hotel in block letters on a paper from the spiral-bound notebook kept at the ready in his jacket pocket. “Here. The Seaman’s Home, in Tórshavn. Jonathan Brand.”

“You should consider changing your reservation to the Hafnia.”

“Oh, Christ,” said Jonathan.

“Pardon?”

“Nothing. Where do I get the bus into town?”

The clerk leaned over his desk and pointed to the left. Then he said, “Excuse me, sir, but how long are you planning to stay in the Faroes, in the event that your luggage arrives after the following Tuesday and we cannot forward until the week succeeding?”

“Don’t worry.” Jonathan had the small pleasure of turning his back on the clerk. Over his shoulder he said, “I’ll be there for a year.”

In the bus he stayed awake only long enough to determine that Iceland looked like the moon, or maybe Mars. The terrain—he couldn’t call it earth because it seemed to be lava—was red and rippled as if frozen in mid-flow. Deposited at his hotel, he trudged down a clean bare corridor to a clean bare room where a white eiderdown puff occupied his bed. Jonathan got underneath it and slept for twelve hours.

He woke shortly before midnight, hungry and hot. A sulfurous atmosphere pervaded the room, along with a weak but insistent streetlight. Was someone banging on the door? He sat up to sort all this out. None of it was as it seemed: the banging and the sulfur were both emanations of the

radiator. Sulfur springs, he remembered, provided heat to Iceland. He put his hand on the white iron and got a burn and a bang for a reprimand. As for the streetlight, it was everybody’s favorite northern fantasy, the midnight sun. A tired-looking item, it perched above a corrugated tin roof across the street, pale pink, flat, smaller than a moon.

Food, he decided—although he also wanted, with equal fervor, a shower, clean clothes, darkness, and the rustling of leaves at night in warm, moist Cambridge.

Nobody was at the front desk. A teenager was sleeping in a chair beside the hotel entrance, though, so Jonathan approached him and coughed. He didn’t wake. “Ahem,” said Jonathan. “Hey.” He touched the boy’s arm.

“Rrrrn,”

said the boy. Then he said some irritated things in Icelandic, which Jonathan hadn’t learned because it had been difficult enough to learn Faroese. But the gist was clear.

“Food.” Jonathan pointed to his mouth. “Hungry.” He tried the Faroese word for hungry, and the boy laughed.

“No, no, no,” he said. “English? You English?” Then: “No eating now here.”

“But I must.”

“I brother he fishing in Liverpool.”

Jonathan nodded. “Bread,” he said, chewing his finger. He ran through his entire repertoire of food in Faroese: potatoes, soup, cheese, fish, and meat. Fruit and vegetables were not available there.

“I Lars. I brother he fishing in Newfoundland.”

“You said Liverpool.”

“I Lars.”

“Johan.” This was Jonathan’s first opportunity to use his new name.

“Johan.” Lars put out his clean Icelandic hand. “Be.” He indicated the floor a few times with his forefinger, and Jonathan decided he was being told to wait. Lars went away, behind the front desk. For the few minutes he was gone,

Jonathan stared out the hotel’s glass door at the lurid light on the street. The shadows of the buildings were long and faint, like the light of the sun. A group of boys about Lars’s age tumbled into view around a corner, drunk, silent with concentration on staying upright, all with their eyes closed. They were wearing Nike running shoes. Jonathan thought of the stories he’d heard around the anthropology department of Bushmen in Bermuda shorts, Sarawak chieftains with transistors pressed to their bone-bedecked ears; Nikes on white men were less jarring, maybe, but still he felt cheated.

Lars came back with his hands full: a beer, half a loaf of bread, a hunk of cheese, a pyramidal cardboard container. He shook this last in front of Jonathan’s nose and said, “Excellent.”

“Hvat?”

What? But why ask, as the answer would be incomprehensible. It was.

“Skyr.”

Lars summoned from his depths an English equivalent: “Yaaoort.” He tugged rhythmically on an invisible object. Jonathan’s mouth was full of saliva. He grabbed the bread. Lars held on to the beer and resumed his seat by the door.

Jonathan alternated bites of bread with bites of cheese. He didn’t understand how to open the “excellent” container, so left it alone. Lars gurgled his beer slowly. The sunlight changed color, taking on a twilight blueness that comforted Jonathan because it reminded him of the earth, whereas the true midnight sun had been extraterrestrial in aspect. Lars opened the container for him by revealing a little hole hidden under a tab near one of the points. It was yogurt—a delicate, sweet yogurt as different from American yogurt as the Icelandic sun was from the sun that shone on Boston. Jonathan leaned against the wall drinking yogurt, entirely happy.