Faldo/Norman (33 page)

Authors: Andy Farrell

Norman’s first big coup came just months before the 1996 Masters. In January that year Acushnet bought out Cobra and Norman’s initial $2 million stake in the latter realised a cool $40 million. A turf company proved another successful venture and he was off and running in the corporate world. From time to time, given his golfing and business pedigree, Norman’s name crops up as a possible future commissioner of the PGA Tour.

It is an unlikely fit. He might like the challenge on one level but why would he want to work for a few hundred moaning golf pros rather than for himself? In any case, he has never got on with the incumbent, Tim Finchem. They clashed a number of times through his career, most recently over the format for the Presidents Cup, and in the autumn of 1996 Norman was irked when Finchem announced a series of World Golf Championships to start in 1999. A couple of years earlier, Norman had supported an idea to link up some of the best tournaments from all over the globe under one umbrella – effectively a world tour. He wanted the best players to play against each other more often, as this rarely happened outside the majors.

But Finchem, fearing loss of control and television rights, knocked down both the plan and Norman’s involvement before responding with his own WGC proposal. Initially, the idea was to play them around the world but soon enough they became permanently situated in the United States. The effects of various scheduling changes and ever greater revenues from television and sponsors has led to a two-tier landscape where either all the top players are playing in the same tournament, or they are not, and

the former are chiefly located in America. As Matt Kuchar said in November 2013, what Norman had suggested years ago had pretty much come about.

Faldo’s business ventures all tended to be a bit more stop-start. But then his whole life seemed that way for a while. He broke up with his long-term coach David Leadbetter and his caddie Fanny Sunesson broke up with him. Management companies and business advisers came and went. His relationship with Brenna Cepelak came to an end, at which point she took a nine-iron to his Porsche, and then in 2001 he married Valerie Bercher, whom he met when she was working at the European Masters at Crans-sur-Sierre. They later divorced, though a daughter, Emma, was a joyful addition to the Faldo clan in 2003.

In 2001, in a profile of Faldo in the

Observer Sports Monthly

, Andrew Smith wrote: ‘I put it to Faldo that if Steve Martin was to direct a farce about a man having the most monumental midlife crisis ever, it might look something like his life over the last five years. Nothing was spared. Everything hit the fan. He looks perturbed, then decides that it might be true and laughs.’

Faldo’s life is far more settled these days, built around the foundations of his television career, his course design work and his Faldo Series for junior golfers. All three reveal far more his passion for golf than appeared when he was playing in his prime. Frank Keating once wrote a column in

The Spectator

describing how it was necessary to reassess opinions of Geoffrey Boycott and Ian Botham once they had stopped playing and started commentating. Botham was by far the more popular performer but with microphone in hand Boycott reveals himself as the more passionate observer of his sport.

Faldo admitted to looking on the course like a ‘miserable bugger, a head-down, boring old whatever with no life’. ‘Because I wanted to win,’ he said. ‘I found I needed to stay in that ultra-focused mode to be successful, so that’s what I did.’ A more nuanced description of his play was provided by Lauren St John when she wrote: ‘In actuality, every shot that Faldo plays reveals something about him. The most insignificant of putts and the most ordinary of five-irons show his careful routine, his perfectionism, his boyish enthusiasm for what would seem to be the dullest of challenges, and his stubborn refusal to give up in the worst of tournaments, on the most uninspiring of days. Even Faldo’s soldier-like walk and quick, reluctant waves to the gallery illustrate his self-consciousness and uncomfortable awareness of being watched, as well as his awkward humour and shy pride when a shot comes off.’

Something had to fuel all those hours of practice and it was this: ‘I’ve never been bored with this game at all, not for a single moment,’ he said. ‘I’ve been frustrated, but I’ve never been bored with it.’

Faldo’s strengths as a television commentator are his never-ending fascination with any shot that is in front of him on the screen at any one moment and his ability to communicate the emotions whirling within a player when the pressure is on down the stretch on a Sunday afternoon. It is a shame he was never able to communicate as successfully with the written press. He was done over by the news hounds on the tabloids, of course, which made him retreat, but he could not get along with many of the golf specialists either, who could be critical if the occasion merited it but who were always there to record his many triumphs.

His instinct to stand alone was evident in his Ryder Cup captaincy in 2008. In an era when there are almost as many assistants to the captain as members of the team, Faldo only had

Olazábal to help him out as a solitary vice-captain. Faced with an American team inspired by another of his old rivals, Paul Azinger, it was a rare poor match for Europe. Some of Faldo’s decisions were debatable, but he did not deserve to be pilloried quite so harshly in the newspapers, and by many who, not having been on the scene in his playing days, only knew him by reputation. His unease with the media became a self-fulfilling prophecy that week.

Yet get him going in the right circumstances, perhaps about one of his course designs, and there is no stopping him. Steve Rider, the former front man for BBC golf and author of

Europe at the Masters

, interviewed Faldo many times. ‘Nick has always been a player on and off the course whose enthusiasm for the sport knows no bounds,’ Rider once said. ‘He is genuine. His Junior Series and everything he does for youth golf is genuine and I have the highest regard for him as a player and a personality. For me, Faldo has always been one of the more compelling interviewees. He always comes up with something fresh and surprising. I remember once we did a documentary with him at Muirfield, going over his final round of 18 pars in 1987. He had a vivid recollection of something on every shot, a movement in the gallery, what his caddie said, his mental processes. Absolute awareness of the situation.’

The Faldo Series was launched towards the end of 1996 as an attempt to ‘give something back to the game that has given me so much,’ he said. It has done that. More than 7,000 youngsters aged 12 to 21 benefit from the programme each year and in 2013 the Grand Final was staged at The Greenbrier. There are European and Asian sections and the Series is supported by the R&A and the European and PGA Tours, among others. Rory McIlroy and Yani Tseng are former overall winners while Nick Dougherty was one of the first to emerge as a winner on the European Tour. Faldo is very much hands-on in passing on his tips for success.

‘He was very friendly to me right from the start,’ Dougherty said. ‘I’ve seen him stand out in the rain all day giving lessons to kids and no one ever hears about that stuff. Every young golfer should aspire to be like him.’

In

Life Swings

, Faldo wrote: ‘The youngsters on the Faldo Series must have grown weary of hearing me go on and on about it but it is a message worth repeating time and again: when you play in the four majors, I believe you must treat every shot as history in that your opening drive is as important as your final putt on the 72nd.’

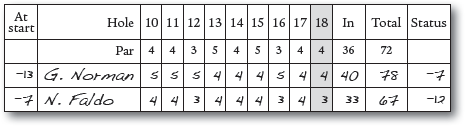

A sixth major championship was about to put Faldo one ahead of Seve Ballesteros as the best of his generation and one behind Vardon as Britain’s greatest ever. Woods is the only player since to go past him (having stalled in his pursuit of Nicklaus on 14), while Mickelson reached five with his Open win at Muirfield. Frank Nobilo, still sitting in on the BBC coverage as Faldo and Norman played the 17th hole, said: ‘A player like Nick seems to thrive on this sort of situation. Deep down he is feeling it but he deals with it better than anyone else. His record proves that.’

Faldo’s drive flirted with the Eisenhower tree on the left of the fairway but missed it and finished in the middle of the fairway. His approach with a wedge finished eight feet from the hole. Not much encouragement for Norman there, but the Australian hit a fine approach himself, to just over six feet. Faldo’s putt was always heading right of the hole and then he marked and stepped back to allow Norman to putt.

In contrast to some of today’s sportsmen (it is usually men) who have made themselves believe that sledging – or ‘silly macho bravado laden willy waving’, as cricket blogger Lizzy Ammon

tweeted during the 2013–14 Ashes series in Australia – is somehow vital to the outcome of the actual game, rather than merely a loss of dignity by the perpetrator, Faldo had not needed to utter a word out of place or act in any way unbecoming. His physical presence in the contest was established simply by the excellence of his play and his determined demeanour.

Peter Alliss said on commentary: ‘Faldo does not appear to be taking any pleasure from the way Norman is struggling. Many of the modern players in all sorts of sports, when someone suffers a misfortune, have a not-so-sly smile, punch the air, give the thumbs up to the crowd, but Faldo at this moment certainly, and all throughout, has shown steely nerve but also great courtesy.’

Norman missed his putt for birdie, the ball moving left-to-right in front of the hole, not hit with sufficient conviction to find the cup. It was the sort of putt that he had holed for three days but not on this Sunday. Both men tapped in for their pars but Faldo was not taking anything for granted. ‘Greg could have holed that putt on 17,’ he said. ‘I could have hit a tree on 18, I could have taken six, he could have had a three. I wasn’t counting my chickens until I hit that last shot out of the bunker onto the green at the last.’

Rick Reilly wrote in

Sports Illustrated

: ‘The last 20 minutes were unlike any seen in the previous 59 Masters. Norman became a kind of dead man walking, four shots behind and all his dreams drowning in Augusta National ponds behind him. Spectators actually looked down, hoping not to make eye contact, as Norman passed among them on his way to the 18th tee.’

Hole 18

Yards 405; Par 4

T

HE FINISH

of the 60th Masters could not come quickly enough. Greg Norman’s loss of a six-stroke overnight lead was now the biggest in major championship history and the turnaround brought back memories of Arnold Palmer losing seven strokes to Billy Casper over the back nine of the final round of the 1966 US Open, Casper winning in a playoff the next day. Not even the possibility of a playoff remained as a lifeline for Norman. Nick Faldo, four behind on the 8th tee, now led by four. Both men just wanted to get the last hole out of the way.

Faldo drove into the second bunker on the left and then did a ‘Sandy Lyle’ – hitting his second shot on the green and holing the putt for a birdie. In 1988, Lyle hit a one-iron into the first of the two fairway bunkers – the ones Ian Woosnam flew when he won the Masters in 1991 – and struck a seven-iron onto the green, the ball rolling back off the ridge in the middle of the green. Then, Lyle had needed to make the putt to become the first Briton to win the Masters, whereas Faldo had the luxury of a huge lead. Still, the relief was palpable when his nine-iron safely found the green, the ball again trickling up the bank towards the top tier but then rolling back gently to 15 feet.