Faldo/Norman (20 page)

Authors: Andy Farrell

When the defending champion at the 60th Masters was asked for his decisive hole at Augusta, Ben Crenshaw nominated the 10th: ‘Because it gets you in the mood for the back nine.’ He might say that, given he holed an outrageous putt from nearly 70 feet on the 10th green on the way to his first Masters victory in 1984. ‘It was absolutely off the charts,’ he said. ‘After it went in, I began to think it might be my day.’

Norman’s history at the hole was not as encouraging. In 1981, his first Masters, he was just off the lead when he hooked into the trees at the 10th and took a double bogey six. Five years later, he

had a four-putt on the 10th green for another six on the Friday. On the Sunday, which he had started at the top of the leader-board, he was still in a share of the lead when he took another six at the 10th. His drive hit a tree on the left and he had a long way to go for his second, which he hit short and crooked. He then chipped from behind a pine over the green into a bunker and took three to get down from there. Up by the clubhouse, his wife Laura sighed: ‘Not the 10th again.’

It was the year, of course, of Nicklaus’s last golden afternoon at the Masters and the scene at the 10th was beautifully described by Peter Higgs, the

Mail on Sunday

golf correspondent who, having a day at leisure with his next deadline almost a week away, had walked the first nine holes with Sandy Lyle, who happened to be playing with Nicklaus. Although tempted to return to the cool of the media centre to watch the rest of the action on television, he made a surprising decision to stay on the course. ‘There seemed little point in trudging out into the countryside to stay with two players who were simply making up the field. But for some reason I did,’ Higgs wrote in an essay in the sporting anthology

Moments of Greatness, Touches of Class

.

‘The 10th is a wonderful long downhill par-four, which slopes up again to a green shaded by towering pine trees and decorated with dogwood and azaleas. It provided me with a lasting image of the day. I walked down the hill alone as my colleagues had hurried away to meet approaching deadlines or had given up this pair as a lost cause. By the time I reached the green, I had to stretch to see Nicklaus hole a 20-foot putt to go four under par. I remember being singularly unimpressed and having a feeling of contempt for the Americans all around me who were whooping and hollering and shouting: “Go get ’em, Jack”, and “Way to go, Jack.”

‘As I stood there impassively I knew that this man could not possibly win. His fans were making fools of themselves.’ But they

weren’t and he could. Higgs walked all 18 holes and saw all 65 shots that day played by the six-time champion and 18-time major winner.

Back to Norman and his adventures at the 10th: when he finished third behind Crenshaw in 1995 the Shark chipped in for a birdie here in the final round and afterwards boldly announced: ‘Anybody who writes that the 10th is my nemesis, I’ll wring their neck.’

In 1996 he parred the hole for the first three days. But it got him again on the Sunday. Faldo had the honour and his drive found the middle of the fairway. Norman hit a three-wood and came up some yards short of the Englishman. Norman’s approach was pulled, though it just stopped on top of a mound on the fringe to the left of the green rather than rolling down the bank towards the gallery. Faldo now stood over his second shot and Dave Marr on the BBC said: ‘This is not a man you want to be giving this much room to, by the way. He is a cold player when he plays and it is beautiful to watch how he takes apart a golf course.’ His nine-iron did not flirt with the left side of the green where the pin was but found the centre of the green, 18 to 20 feet short and right of the hole.

Norman then hit a stiff-wristed chip that came off far too hot and ran on ten feet past the hole. Asked later about his worst couple of mistakes, he would say: ‘If I had my second shot into 9, I’d have that again and just hit it six feet harder. And probably my chip at 10.’ Australian golfer and commentator Jack Newton noted to

Golf Digest

the comparison with the third hole of the four-hole playoff for the 1989 Open at Royal Troon, which Norman lost to Mark Calcavecchia. ‘Greg birdied the first two holes of the playoff,’ Newton said. ‘Then it got to the 17th hole and he hits it just off the back edge. He could have putted it, hit it with a seven-iron, anything. Instead, he tries to hit a fancy,

spinning chip. Seven years later he tried the same fancy chip at the 10th hole in the final round at Augusta. He still wants to play the low-percentage shot he’d play in the first round, and that isn’t the way to win majors.’

Faldo’s birdie putt came up just a few inches short and, momentarily forgetting not to show any emotion, he turned away muttering to himself. But after he had walked up and tapped in for another comfortable, priceless par, the mask of inscrutability was back in place. Norman spent a long time standing over his putt with his left arm dangling freely, trying to ease away the tension, before regripping the putter with both hands. The par-save attempt was a poor one, the ball always on the low side. It was his second bogey in a row but the third hole in a row, and the fourth in five, where Faldo had gained a stroke. The lead was now only one shot.

Lauren St John, of the

Sunday Times

, saw Norman’s manager Frank Williams ‘rushing numbly down the hill in the sultry heat, panicking about Laura’, Norman’s wife. ‘She’s a wreck,’ Williams said. That evening Faldo was asked when he sensed Norman was really in trouble. ‘I thought 10,’ he said. ‘It was down to a shot. He missed his chip shot, and I felt then we were getting tight.’ He added: ‘Once I realised that Greg was in trouble, then I was just getting harder. Not harder on myself, just doing everything a little bit better. I mean, the pressure was immense.’

Between 1970 and 1995, 20 times out of 26 the leader with nine holes to play went on to win the Masters. The two most recent times that had not been the case were in 1990 (Ray Floyd) and 1989 (Scott Hoch). On both occasions the eventual winner was Faldo.

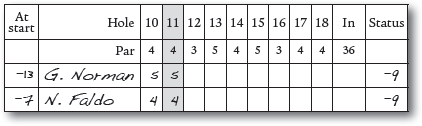

Hole 11

Yards 455; Par 4

N

ICK FALDO

’s favourite golf course would be a composite including features such as the coastline at Pebble Beach, the of Augusta and the atmosphere of St Andrews. At the 2013 Open Championship, where Faldo was tempted out of retirement to play in his first event for three years, he added: ‘But then you have to think of memorability and I’ve got a pretty special place right here, the 18th green at Muirfield.’ Faldo won the Open at St Andrews in 1990 at a canter. But for his two victories at Muirfield in 1987 and 1992 he was racing flat-out until the tape, only confirming possession of the claret jug on the 18th green. No wonder it is one of his favourite places in golf.

Another is the 11th hole at Augusta National.

For his first two Masters wins, in 1989 and 1990, Faldo found 72 holes were not enough. Each time he was forced into a sudden-death playoff and it took two extra holes to prevail. By the time he did so, he was standing on the 11th green, far from the clubhouse, in the gloaming and, on at least one occasion, in the rain. His hallelujah moments came in Amen Corner. The 11th green was also the exact spot of Larry Mize’s outrageous chip at the 1987 Masters.

If Augusta only ever became a scene of recurring nightmares for Greg Norman, it was always a dreamland to Faldo, from the moment when colour television first brought the sights and sounds of the golfing funfair to a 13-year-old watching late into the night over the weekend of Easter 1971. ‘Even though the game and the great players were completely unknown to me, Jack Nicklaus made a clear impression on me,’ Faldo wrote in his 1994 book

Faldo – In Search of Perfection

. Tony Jacklin’s Open victory of two years earlier had clearly passed him by. But now Nicklaus ‘drew my attention like a magnet’, even though the Golden Bear did not win, finishing joint second with Johnny Miller, two behind Charles Coody.

‘I was struck that weekend,’ Faldo went on, ‘by the same things that hit everyone who experiences Augusta for the first time: the tall, dark pines, the green grass and the colourful golfers. What most impressed me, however, was the sound. Not the whooping of the crowds – though that is thrilling the first time – but the very sound of the club on ball and the rush of air as the ball set off. I suppose the closeness and height of the trees exaggerates the sound, but I was very aware of that wonderful swoosh – the hit and the ball’s launch are really all one noise. When I took up the game, one of the things I was seeking was to recreate that unique sound. It was a long time – a year or so – before I hit one properly and heard it again.’

That was doubtless on the practice range at Welwyn Garden City Golf Club, in Hertfordshire, where the teenager virtually took up residence, swiftly making a dent in the 10,000 hours of purposeful practice that is the basic requirement for expertise, according to popular recent theories. Swimming, athletics and cycling never had the hold on the youngster that golf did and in 1973 Faldo and his father, George, set off for Troon and his first visit to the Open. Sleeping at a campsite at night, the not-quite

16-year-old spent the long hours of daylight watching as much golf as he could find, being particularly impressed by watching Tom Weiskopf ‘pinging’ iron shots on the range while wearing only regular shoes, without any grip. ‘That’s impressive, he’s going to win,’ Faldo-the-future-television-analyst said to himself and he was right.

Three years later and Faldo was playing in the Open. He made his debut in the Masters in 1979 although after that he did not return to Augusta until 1983. That season he went on to win five times on the European Tour and claimed the Harry Vardon Trophy as the leading money winner. His success, which up until then also included three PGA Championships in four years from 1978, was helped by his putting, which could be brilliant but streaky and inconsistent. Tall and handsome, his swing was upright, flowing and graceful. ‘In those days he had a long overswing, a tremendous, willowy hip slide, a typically young man’s action which propelled the ball enormous distances, not always in the desired direction,’ wrote Peter Dobereiner.

A tendency to break down under the greatest pressure became apparent, however. At Birkdale in the 1983 Open, he led briefly during the final round but crashed to a 73 to finish five behind Tom Watson. At the 1984 Masters, he was in contention on the last day but went out in 40 and a 76 left him eight behind Ben Crenshaw. ‘By halfway through Sunday’s final round, the greens could have been written in hieroglyphics such was the difficulty I was experiencing in reading them, while the fairways, previously so accommodating, suddenly appeared narrower than a ten pin bowling alley,’ Faldo wrote in

Life Swings

.

It was late in 1984, at Sun City, in South Africa, that Faldo met a man making his way as an instructor, David Leadbetter. Faldo admits to a fascination with taking things apart to see how they work – one of the things he found most enjoyable

about cycling was getting a new bike, taking it apart and putting it back together again – and he had always taken the same approach to his swing. In Leadbetter he found someone on a similar wavelength. They started working together properly in 1985 and for 18 months remodelled every part of Faldo’s swing – backswing, downswing, follow-through and everything in between. ‘What gave me encouragement,’ Faldo said, ‘that I was on the right track was that suddenly I could hit a shot or a series of shots that were better than anything before. I’d hit a drive with real penetration or some iron shots which went where they should go. They were the stepping stones, the little boosts that kept me going.’

His form in tournaments naturally suffered at first. In 1987, he did not qualify for the Masters but happened to be going through Atlanta Airport, on his way to Hattiesburg, Mississippi, when he bumped into a bunch of European players and officials, and representatives of Her Majesty’s Press, who were in transit to Augusta. ‘The golfing world was assembling for the Masters and I was heading for a tumbleweed town in the woods somewhere,’ Faldo wrote in

Life Swings

. ‘I felt grievously humiliated.’

Instead of heading to the first major of the year, Faldo was entered into the Deposit Guaranty Classic, along with everyone else who had not qualified for Augusta. Still, it was a turning point, with four consecutive rounds of 67 leaving him second to David Ogrin. He returned to Europe to win the Spanish Open, and then that summer he claimed the Open for the first time at Muirfield. ‘I had finally proved to myself that I had been right all along to go back to the beginning and start again,’ he said. ‘I had now achieved more with the new version than I ever could have done with the old.’

The following April, Faldo was back at Augusta and finished tied for 30th in the 1988 Masters. After his round he went up on

to the balcony of the clubhouse to watch the closing stages of Sandy Lyle’s victory alongside the BBC’s Steve Rider. Lyle, with his effortless power and easy grace, seemed to be ahead of Faldo at every stage of their careers. Lyle won the Open first, in 1985, and now that Faldo had a claret jug, Lyle had added a green jacket. Mind you, if you were European and a golfer and swinging a club in the 1980s or 1990s, you weren’t anyone if you didn’t have a green jacket.