Eyes on the Street: The Life of Jane Jacobs (5 page)

Read Eyes on the Street: The Life of Jane Jacobs Online

Authors: Robert Kanigel

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Women, #History, #United States, #20th Century, #Political Science, #Public Policy, #City Planning & Urban Development

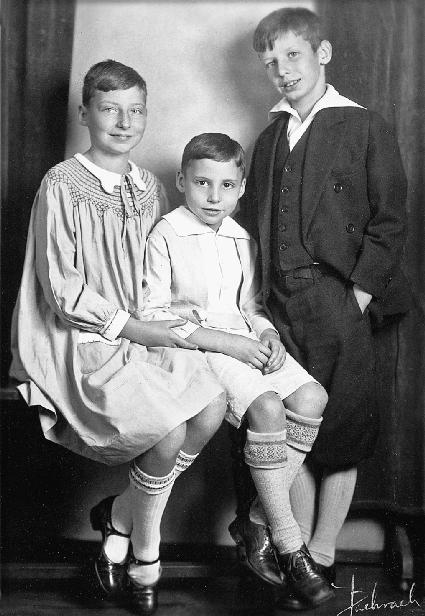

Jane, at left, in about 1927, age eleven, with brothers Jim and John

Credit 3

Too good to be true, of course. And maybe there wasn’t among them much latitude, or encouragement, to explore personal feelings or doubts, or to let boredom, annoyance, or futility have their day; this was part of the family culture, too. But allowing for memories sweetened by time and a streak of family boosterism, surely something healthy and productive was alive among them. Betty would become vice president of a

major New York interior design firm and was later active in the Esperanto League. John would become a judge, for years a justice of the 4th District U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, from which he’d issue important and controversial antisegregation decisions. Jim, most of his adult life spent in southern New Jersey, would have a successful career as a chemical engineer for a major oil company and, on the civic front, help transform a tiny local college into a major community asset. Jane would write books and change the world. Each remained married to the same spouse their whole lives—mostly, it seems, happily. The four of them found plenty to disagree about. Their voices could rise. But the way their children tell it, they had fun, and were determined to extract every last fresh nugget of pleasure and interest from the world.

—

One day when Jane was seven, sister Betty, by then a Girl Scout, took her on a hike. Jane remembered the toasted marshmallows that evening, but more vividly the moment when Betty bumped her foot on a rock. “

That’s puddingstone!” Betty cried out.

What a great word!

Jane thought, and what an interesting geological anomaly: a mass of rounded stones and pebbles embedded in a sandy, cement-like matrix. Here, at age seven, was something of the peculiar doubleness of Jane’s intellect: her lifelong fascination with the world right in front of her nose—an explorer’s fascination, a journalist’s, a scientist’s; and, right beside it, a delight in language and all its nuances of sound and meaning.

At six or seven, Jane was reading pretty much everything, sometimes trailing her mother around the house, book in hand, asking about words she didn’t know. She liked nursery rhymes and traditional songs, thought about what they meant. “When Good King Arthur Ruled This Land” tells of pudding stuffed with “great lumps of fat as big as my two thumbs”; Jane saw in it

a distaste for profligacy. She loved

The Three Musketeers.

She buried herself in

The Book of Knowledge

, a children’s encyclopedia, popular and fun—if, in son Jim’s words, “chock full of egregious misinformation, and racist.” She discovered Dickens’s compulsively readable

A Child’s History of England:

So, Julius Caesar came sailing over to this Island of ours, with eighty vessels and twelve thousand men. And he came from the French coast between Calais and Boulogne, “because thence was the shortest passage into Britain”; just for the same reason as our steamboats now take the same track every day. He expected to conquer Britain easily; but it was not such easy work as he expected.

As a young girl Jane may not have talked of it so freely, but much later she’d often refer to the chats she’d have in her imagination with historical figures. “Since I was a little girl I’ve been

carrying on dialogues with them in my head just to keep from being bored.” First was Thomas Jefferson—until, that is, “I exhausted my meagre knowledge of what would interest Jefferson. He always wanted to get into abstractions.” She turned to Benjamin Franklin, who, she advised an interviewer once, was interested in “nitty-gritty, down-to-earth details, such as why the alley we were walking through wasn’t paved, and who would pave it if it were paved. He was interested in

everything.

” She’d tell him how traffic lights worked, observe his surprise at how modern women dressed.

She set no limits to her imagination and apparently no one tried to do it for her. “Where I grew up in Pennsylvania,” she’d write, “the children believed that on a night in August

the lakes turned over.” Later, she learned better, but just then “I imagined this marvel as a dark, whispered heaving and slipping of the waters with bright fish tumbling through. We knew when it had happened because we would find floating fragments of bottom weeds and in the top few feet of water, usually so clear, bits of fine muck and a rank smell.”

Early on, Jane fell into poetry. In the 1950s, her mother gathered some of her youthful efforts and bound thirty or so of them into a little packet. Playfully or modestly, it’s not clear which, they were “published” as the work of one

Sabilla Bodine, a forebear, five generations back, on Bessie’s side. Jane’s poems bore names like “A Mouse” and “Washing” and “Winter,” and look their age; they seem very much the juvenilia they are. Mostly, they rhyme: “I wonder if by any chance / Zebra babies like to dance.” Mostly, too, they are sweet, sometimes cloyingly so. On the other hand, they are striking for their varied subject matter and style. They include Aesop-like fables involving flies, fleas, and mice; micro-histories of Abraham Lincoln, the pirate Blackbeard, and the French poet François Villon. And warm recollections of Girl Scout camp: “In the dusky moonlight / by the flickering fire / Listening to the whispering leaves / That never seem to tire…” And delight in silly wordplay: “The baby is crying ’cause puss caught a mouse / Dingsy, dangsy, dito…” Or: “One day the

willowing Willow / Willowing like a willow / Saw a waddling / Wallowing / Dolphin / A-wallowing in the sea.” A few, just a bit more sophisticated, draw young Jane closer to us: “Small puddles, token of a rainy day / Have always lured me from my schoolward way / I want the crash of thunder, and the rain / I want it beating on my head again! / How can I stay at home, a warm dry place / When I have felt wet hemlock cross my face?”

Whatever we might think of these youthful efforts, she kept at it. Several of her poems were published—later, as an adult, and then, as an adolescent: “

Greetings to you from the office of

The American Girl

,” the editor, Helen Ferris, wrote ten-year-old Jane in January 1927. “Miss Yost”—perhaps an assistant, perhaps Jane’s teacher—“has just sent me some of the poetry you have written and I want to tell you how much I like it.” She couldn’t use it all, of course, “but you may be sure that I will use at least part of your poetry just as soon as we possibly can.” Jane didn’t write much poetry as an adult, but she would always read it, and recite it, from what one of her children calls her “

endless store” of Shakespeare and Mother Goose, Longfellow, Lindsay, and Frost.

Between her parents, Jane was closer to her father. She’d remember him as “

intellectually very curious, bright and independent. He was locally very famous as a diagnostician,” a kind of Sherlock Holmes of bodily clues. He used his eyes and ears. “I loved to hear his stories about how he found out this and that.” Dr. Butzner, bald and mustached, was forever reading the encyclopedia, not to idly amass informational factoids but to sink into its sometimes long, meaty essays, often discuss them with his family. Jane was about seven, she’d recall, when Poppa would ask her to retrieve for him one or another volume, like the one with

Gr

or

Ro.

“Then, while I looked at the drawings and plates, while he turned the pages, he would regale me with interesting bits” about the Greeks and the Romans. “The bit I liked best was how the barbarians demanded three hundred pounds of pepper from Rome, as part of a ransom payment. He said that as ransoms go, that was a pretty civilized demand.”

Jane’s relationship with her mother was more problematic. The old lady, hair up in a tidy bun, always neatly dressed and groomed, whom her grandchildren would remember warmly as storyteller and gardener, author of vast waffle breakfasts, likable, intelligent, principled, sometimes funny or wry, always a close and attentive listener, didn’t entirely square with the much younger woman, not so long out of Espy,

Pennsylvania, whom Jane, as an adolescent, knew as her mother. Bess would grow more tolerant over her 101 years; a staunch Republican, she’d

resign from Daughters of the American Revolution when it condemned Jackie Kennedy for sending UNICEF Christmas cards from the White House. Jane, as an adult, recognized her virtues and was perfectly capable of painting a balanced portrait of her. Of how she would walk Jane around the garden each morning, pointing out this new growth or that. Or how, during a coal strike once, she tightly rolled up wet newspapers, one by one, to make

artificial logs. “I can still see you in my mind’s eye,” Jane wrote her affectionately, “dipping them into a bucket of water and drying them in the back yard.” Jane would tell how her mother “became

the night supervising nurse at an important hospital in Philadelphia”; there’s real pride there. She’d tell of her mother’s compassion. As a nurse, most of her patients were poor. “She would tell me

how limited their lives were,” their poverty

eating

at her. In 1975, as her mother approached one hundred and grew more feeble, Jane would write that she still

hadn’t “come to grips with the idea of this wonderful old lady wearing out…I’m used to her being in existence [and] besides, in fact I love her.”

But most of that came later and, as a young adult, and earlier in her adolescence, and maybe going back further still, her mother rankled her. She was “

quite prissy,” Jane wrote, “and particularly about anything to do with sex.” Even later, in the 1950s, Jane could write an editor how her mother “

to this day astonishes me by her capacity for disapproval of the earthy.” A ditty making the rounds after World War I had somehow inspired Jane to recite it around the house:

Kaiser Bill went up the hill

To take a peek at France

Kaiser Bill came down the hill

With bullets in his pants.

Don’t sing that

, said her mother; “pants,” of course, were underpants, and Jane was not to mention them. But of course Jane kept at it:

…with bullets in his…

, whereupon Bess slung Jane over her knee and spanked her. “But I was going to say

trousers

,” Jane wailed.

Jane would picture her mother’s mind as a veritable

minefield of small-town narrow-mindedness. She remembered being ordered not to play with a Chinese girl in the neighborhood. She was advised that people

from Sicily were slum dwellers—for the sole, if unassailable, reason that they were Sicilian. Politically, her mother was much more conservative than her father. When young, she’d been a strong Temperance advocate (as was enough of the country to get us Prohibition). Red wine was “Dago red,” one strike against it, of course, being that it was Italian; when Dr. Butzner occasionally got a bottle of wine from a Sicilian coal miner he’d treated, Mrs. Butzner was known to turn it into vinegar if she got her hands on it, or else just pour it down the drain.

So, as many an adolescent before and since, Jane wrangled with her mother. Maybe worse, she felt “

I had to shut up about things that I really would have liked to talk to her about.” The detailed, pages-long, idea- and fact-filled missives Jane wrote to her mother much later—on farming practices in the Canary Islands, acupuncture, or the “micro-balance-of-nature” represented by ladybugs eating aphids—testified to her own need to

say

, to speak, to explain, and

also

to her mother’s receptivity. But again, that came later. As a teenager, especially on more intimate subjects, she didn’t feel she had her mother’s ear.

This seems to have been about as troubled as Jane ever felt at home. Not that any hurts she did experience were trifling to her; how could they be? But set against the whole fabled, fraught landscape of children and parents, little in her life on Monroe Avenue hints at subterranean terrors or cries out for probing scrutiny.

Jane and her family inhabited the fat, happy middle of American economic and social life. They mostly had enough money, but not too much. Jane grew up in a nice house, on a pretty street of nice houses, in an upper-middle-class neighborhood; the house even had an early dishwasher. But she wasn’t entirely cut off from the less lucky. She’d remember a down-at-the-heels area near their house, “

the Patch,” that had no sidewalks; “you just knew when you went into the Patch that this was a miserable place.” She knew about the men who worked the mines; some of them were her father’s patients. She heard from her mother about her nursing days and her poorer patients.

Her childhood was sprinkled with a full share of the familiar and the comfortably unremarkable. She went to church—Green Ridge Presbyterian, a few blocks away. (Jane was “never at war with the church,” one of her children would say, “just bored.”)

She traded cards with her friends—of political figures, it seems, not baseball players. She played pirates, the loser walking the plank atop an old stump. She played

cowboys and Indians. She sometimes roller-skated to school. She had a hiding place, in a cleft in a nearby cliffside, where she could

secrete treasures. Like her sister, she joined the Girl Scouts, went to camp, enjoyed crafts. She’d remember the summer weeks when the

Chautauqua came to Scranton, with its great children’s programs. She loved listening to her parents and grandmothers talk about their childhoods—like her grandmother, on wash days, making soap from fat and wood ash, or her mother, when she was eight, flipping the switch on the town’s first electric lights. She played pranks on her siblings, one time tricking brother John into giving up

his favorite shirt. Come Christmas, the

tree in the parlor was so cropped and positioned that it poked right up through the stairwell to the second floor, from where Jane and John, hidden, could pull on gossamer-thin threads tied to its branches, the neighbor children invited in to marvel at the tree wriggling and waving in the unseen breeze.