Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things (77 page)

Read Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things Online

Authors: Charles Panati

Tags: #Reference, #General, #Curiosities & Wonders

Tabasco Sauce

. Amidst the coastal marshes of Louisiana’s fabled Cajun country is a prehistoric geological phenomenon known as Avery Island. An upthrust salt dome six miles in circumference, the island is covered with meadows and was the site of America’s first salt mine, which still produces a million and a half tons of salt a year. Avery Island is also the birthplace of Tabasco sauce, named by its creator, Edmund Mclhenny, after the Tabasco River in southern Mexico, because he liked the sound of the word.

In 1862, Mclhenny, a successful New Orleans banker, fled with his wife, Mary Avery Mclhenny, when the Union Army entered the city. They took refuge on Avery Island, where her family owned a salt-mining business. Salt, though, was vital in preserving meat for the war’s troops, and in 1863 Union forces invaded the island, capturing the mines. The McIhennys fled to Texas, and returning at war’s end, found their plantation ruined, their mansion plundered. One possession remained: a crop of capsicum hot peppers.

Determined to turn the peppers into income, Edmund Mclhenny devised a spicy sauce using vinegar, Avery Island salt, and chopped capsicum peppers. After aging the mixture in wooden barrels for several days, he siphoned off the liquid, poured it into discarded empty cologne bottles, and tested it on friends. In 1868, Mclhenny produced 350 bottles for Southern wholesalers. A year later, he sold several thousand bottles at a dollar apiece, and soon opened a London office to handle the increasing European demand for Cajun Tabasco sauce.

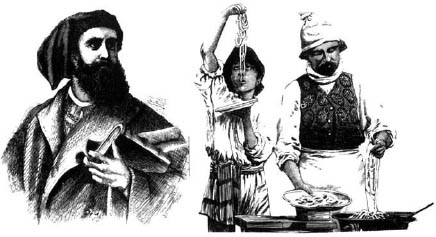

Marco Polo (left) and the Oriental origin of spaghetti, meaning “little strings

.”

Clearly contradicting the standing joke that there is no such thing as an empty Tabasco bottle, the Mclhenny company today sells fifty million two-ounce bottles a year in America alone. And the sauce, made from Edmund Mclhenny’s original recipe, can be found on food-store shelves in over a hundred countries. Each year, 100,000 tourists visit Avery Island to witness the manufacturing of Tabasco sauce, and to descend into the cavernous salt mines, which reach 50,000 feet down into geological time.

Pasta: Pre-1000

B.C

., China

We enjoy many foods whose Italian names tell us something of their shape, mode of preparation, or origin:

espresso

(literally “pressed out”),

cannelloni

(“big pipes”),

ravioli

(“little turnips”),

spaghetti

(“little strings”),

tutti-frutti

(“every fruit”),

vermicelli

(“little worms”),

lasagna

(“baking pot”),

parmesan

(“from Parma”),

minestrone

(“dished out”),

and pasta

(“dough paste”). All these foods conjure up images of Italy, and all derive from that country except one, pasta (including vermicelli and spaghetti), which was first prepared in China at least three thousand years ago, from rice and bean flour.

Tradition has it that the Polo brothers, Niccolo and Maffeo, and Niccolo’s son, Marco, returned from China around the end of the thirteenth century with recipes for the preparation of Chinese noodles. It is known with greater certainty that the consumption of pasta in the form of spaghetti-like noodles and turnip-shaped ravioli was firmly established in Italy by 1353, the year Boccaccio’s

Decameron

was published. That book of one hundred fanciful tales,

supposedly told by a group of Florentines to while away ten days during a plague (hence the Italian name

Decamerone

, meaning “ten days”), not only mentions the two dishes but suggests a sauce and cheese topping: “In a region called Bengodi, where they tie the vines with sausage, there is a mountain made of grated parmesan cheese on which men work all day making spaghetti and ravioli, eating them in capon’s sauce.”

For many centuries, all forms of pasta were laboriously rolled and cut by hand, a consideration that kept the dish from becoming the commonplace it is today. Spaghetti pasta was first produced on a large scale in Naples in 1800, with the aid of wooden screw presses, and the long strings were hung out to dry in the sun. The dough was kneaded by hand until 1830, when a mechanical kneading trough was invented and widely adopted throughout Italy.

Bottled spaghetti and canned ravioli originated in America, the creation of an Italian-born, New York–based chef, Hector Boiardi. He believed Americans were not as familiar with Italian food as they should be and decided to do something about it.

A chef at Manhattan’s Plaza Hotel in the 1920s, Boiardi began bottling his famous meals a decade later under a phoneticized spelling of his surname, Boy-ar-dee. His convenient pasta dinners caught the attention of John Hartford, an executive of the A & P food chain, and soon chef Boiardi’s foods were appearing on grocery store shelves across the United States. Though much can be said in praise of today’s fresh, gourmet pastas, served

primavera, al pesto

, and

alla carbonara

, Boy-ar-dee’s tomato sauce dishes, bottled, canned, and spelled for the masses, created something of a culinary revolution in the 1940s; they introduced millions of non-Italian Americans to their first taste of Italian cuisine.

Pancake: 2600

B.C

., Egypt

The pancake, as a wheat flour patty cooked on a flat hot stone, was known to the Egyptians and not much different from their unleavened bread. For prior to the advent of true baking, pancakes and bread were both flat sheets of viscous gruel cooked atop the stove.

The discovery of leavening, around 2600

B.C

., led the Egyptians to invent the oven, of which many examples remain today. Constructed of Nile clay, the Egyptian oven tapered at the top into a truncated cone and was divided inside by horizontal shelves. At this point in time, bread became the leavened gruel that baked and rose inside the oven, while gruel heated or fried on a flat-topped stove was the pancake—though it would not be cooked in a pan for many centuries.

The pancake became a major food in the ancient world with the advent of Lenten shriving observances in

A.D

. 461. Shriving was the annual practice of confession and atonement for the previous year’s sins, enacted as preparation for the holy Lenten season. The three-day period of Sunday, Monday,

and Shrove Tuesday (the origin of

Mardi Gras

—literally “fat Tuesday” —the day before the start of Lent) was known as Shrovetide and marked by the eating of the “Shriving cake,” or pancake. Its flour symbolized the staff of life; its milk, innocence; and its egg, rebirth.

In the ninth century, when Christian canon law prescribed abstinence from meat, the pancake became even more popular as a meat substitute. And by the thirteenth century, a Shrove Tuesday pancake feast had become traditional in Britain, Germany, and Scandinavia, with many extant rhymes and jingles accompanying the festivities, for example:

Shrove Tuesday, Shrove Tuesday

,

’Fore Jack went to plow

His mother made pancakes

,

She scarcely knew how

.

The church bell calling the shriving congregation became known as the “pancake bell,” and Shrove Tuesday as Pancake Day. A verse from

Poor Robin’s Almanac

for 1684 runs: “But hark, I hear the pancake bell / And fritters make a gallant smell.”

The most famous pancake bell in Western Europe was that of the Church of Sts. Peter and Paul in Olney, England. According to British tradition, an Olney woman in the fifteenth century, making pancakes when the bell tolled, unwittingly raced to church with the frying pan and its contents in her hand. The tale developed into an annual race to the church, with towns-women flipping flapjacks all the way, and it has survived into modern times, with the course a distance of four hundred and fifteen yards. Women competing must be at least eighteen years old, wear an apron and a head scarf, and somersault pancakes three times during the race. In 1950, a group of American women from Liberal, Kansas, members of the local Jaycees, staged their own version of the British pancake race.

The earliest American pancakes were of corn meal and known to the Plymouth Pilgrims as “no cakes,” from the Narragansett Indian term for the food,

nokehick

, meaning “soft cake.” Etymologists trace the 1600s’ “no cake” to the 1700s’ “hoe cake,” so named because it was cooked on a garden-hoe blade. And when cooked low in the flames of a campfire, often collecting ash, it became an “ashcake” or “ashpone.” In the next century, the most popular pancakes in America were those of a talented black cook, Nancy Green, the country’s Aunt Jemima.

Aunt Jemima

. The story of America’s first commercially successful pancake mix begins in 1889 in St. Joseph, Missouri, where a local newspaperman, Chris Rutt, conceived the idea for a reliable premixed self-rising flour. Rutt loved to breakfast on pancakes, but lamented the fact that batter had to be made from scratch each morning. He packaged a formulation of flour, phosphate of lime, soda, and salt in plain brown paper sacks and sold it to grocers. The product, despite its high quality, sold poorly, and Rutt realized that he needed to jazz up his packaging.

The prototype for Aunt Jemima; A crowd in 1882 watches a short-order cook prepare pancakes

.

Enter Aunt Jemima.

One evening in autumn 1889, Rutt attended a local vaudeville show. On the bill was a pair of blackface minstrel comedians, Baker and Farrell, and their show-stopping number was a rhythmic New Orleans-style cakewalk to a tune called “Aunt Jemima,” with Baker performing in an apron and red bandanna, traditional garb of a Southern female chef. The concept of Southern hospitality appealed to Rutt, and he appropriated the song’s title and the image of the Southern “mammy” for his pancake product.

Sales increased, and Rutt sold his interests to the Davis Milling Company, which decided to promote pancake mix at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. Initiating a dynamic concept that scores of advertisers have used ever since, the company sought to bring the Aunt Jemima trademark to life. Searching among Chicago’s professional cooks, the company found a warm, affable black woman, Nancy Green, then employed by a local family. As the personification of Aunt Jemima, Nancy Green served the fair’s visitors more than a million pancakes, and a special detail of policemen was assigned to prevent crowds from rushing the concession. Nancy Green helped establish the pancake in America’s consciousness and kitchens, touring the country as Aunt Jemima until her death in 1923, at age eighty-nine.

Betty Crocker: 1921, Minnesota

Although there was a real-life “Aunt Jemima,” the Betty Crocker who for more than sixty years has graced pantry shelves never existed, though she accomplished much.

In 1921, the Washburn Crosby Company of Minneapolis, a forerunner of General Mills, was receiving hundreds of requests weekly from home-makers seeking advice on baking problems. To give company responses a more personal touch, the management created “Betty Crocker,” not a woman but a signature that would appear on outgoing letters. The surname Crocker was selected to honor a recently retired company director, William Crocker, and also because it was the name of the first Minneapolis flour mill. The name Betty was chosen merely because it sounded “warm and friendly.” An in-house handwriting contest among female employees was held to arrive at a distinctive Betty Crocker signature. The winning entry, penned by a secretary in 1921, still appears on all Betty Crocker products.

American housewives took so believingly and confidingly to Betty Crocker that soon more than her signature was required.

In 1924, Betty Crocker’s voice (that of an actress) debuted on America’s airwaves in the country’s first cooking program, something of early radio’s equivalent to Julia Child, and it was an overnight success. Within months, the program was broadcast from thirteen stations, each with its own Betty Crocker reading from the same company-composed script. The

Betty Crocker Cooking School of the Air

would eventually become a nationwide broadcast, running uninterrupted for twenty-four years.