Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things (42 page)

Read Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things Online

Authors: Charles Panati

Tags: #Reference, #General, #Curiosities & Wonders

One man, John Breck, helped launch the shampoo business in America, turning his personal battle against baldness into a profitable enterprise.

In the early 1900s, the twenty-five-year-old Breck, captain of a Massachusetts volunteer fire department, was beginning to lose his hair. Although several New England doctors he consulted assured him there was no cure for baldness, the handsome, vain young firefighter refused to accept the prognosis.

Preserving his remaining hair became an obsession. He developed home hair-restoring preparations and various scalp-massage techniques, and in 1908 opened his own scalp-treatment center in Springfield. When his shampoos became popular items among local beauty salons, Breck expanded his line of hair and scalp products, as well as the region he serviced. He introduced a shampoo for normal hair in 1930, and three years later, shampoos for oily and dry hair. By the end of the decade, Breck’s hair care business was nationwide, becoming at one point America’s leading producer of shampoos. Of all his successful hair preparations, though, none was able to arrest his own advancing baldness.

Atop the Vanity

Cosmetics: 8,000 Years Ago, Middle East

A thing of beauty may be a joy forever, but keeping it that way can be a costly matter. American men and women, in the name of vanity, spend more than five billion dollars a year in beauty parlors and barbershops, at cosmetic and toiletry counters.

Perhaps no one should be surprised—or alarmed—at this display of grooming, since it has been going on for at least eight thousand years. Painting, perfuming, and powdering the face and body, and dyeing the hair, began as parts of religious and war rites and are at least as old as written history. Archaeologists unearthed palettes for grinding and mixing face powder and eye paint dating to 6000

B.C

.

In ancient Egypt by 4000

B.C

., beauty shops and perfume factories were flourishing, and the art of makeup was already highly skilled and widely practiced. We know that the favorite color for eyeshade then was green, the preferred lipstick blue-black, the acceptable rouge red, and that fashionable Egyptian women stained the flesh of their fingers and feet a reddish orange with henna. And in those bare-breasted times, a woman accented veins on her bosom in blue and tipped her nipples gold.

Egyptian men were no less vain—in death as well as life. They stocked their tombs with a copious supply of cosmetics for the afterlife. In the 1920s, when the tomb of King Tutankhamen, who ruled about 1350

B.C

., was opened, several small jars of skin cream, lip color, and cheek rouge were discovered—still usable and possessing elusive fragrances.

In fact, during the centuries prior to the Christian era, every recorded

culture lavishly adorned itself in powders, perfumes, and paints—all, that is, except the Greeks.

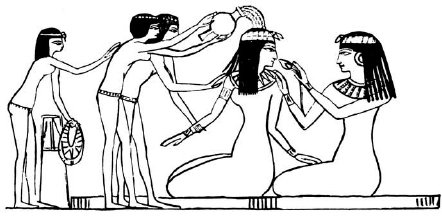

Egyptian woman at her toilet. Lipstick was blue-black, eye shadow green, bare nipples were tipped in gold paint

.

Unlike the Romans, who assimilated and practiced Egyptian makeup technology, the Greeks favored a natural appearance. From the time of the twelfth-century Dorian invasions until about 700

B.C

., the struggling Greeks had little time for languorous pleasures of self-adornment. And when their society became established and prosperous during the Golden Age of the fifth century

B.C

., it was dominated by an ideal of masculinity and natural ruggedness. Scholastics and athletics prevailed. Women were chattels. The male, unadorned and unclothed, was the perfect creature.

During this time, the craft of cosmetics, gleaned from the Egyptians, was preserved in Greece through the courtesans. These mistresses of the wealthy sported painted faces, coiffed hair, and perfumed bodies. They also perfumed their breath by carrying aromatic liquid or oil in their mouths and rolling it about with the tongue. The breath freshener, apparently history’s first, was not swallowed but discreetly spit out at the appropriate time.

Among Greek courtesans we also find the first reference in history to blond hair in women as more desirable than black. The lighter color connoted innocence, superior social status, and sexual desirability, and courtesans achieved the shade with the application of an apple-scented pomade of yellow flower petals, pollen, and potassium salt.

In sharp contrast to the Greeks, Roman men and women were often unrestrained in their use of cosmetics. Roman soldiers returned from Eastern duty laden with, and often wearing, Indian perfumes, cosmetics, and a blond hair preparation of yellow flour, pollen, and fine gold dust. And there is considerable evidence that fashionable Roman women had on their vanity virtually every beauty aid available today. The first-century epigrammatist

Martial criticized a lady friend, Galla, for wholly making over her appearance: “While you remain at home, Galla, your hair is at the hairdresser’s; you take out your teeth at night and sleep tucked away in a hundred cosmetics boxes—even your face does not sleep with you. Then you wink at men under an eyebrow you took out of a drawer that same morning.”

Given the Roman predilection for beauty aids, etymologists for a long time believed that our word “cosmetic” came from the name of the most famous makeup merchant in the Roman Empire during the reign of Julius Caesar: Cosmis. More recently, they concluded that it stems from the Greek

Kosmetikos

, meaning “skilled in decorating.”

Eye Makeup: Pre-4000

B.C

., Egypt

Perhaps because the eyes, more than any other body part, reveal inner thoughts and emotions, they have been throughout history elaborately adorned. The ancient Egyptians, by 4000

B.C

., had already zeroed in on the eye as the chief focus for facial makeup. The preferred green eye shadow was made from powdered malachite, a green copper ore, and applied heavily to both upper and lower eyelids. Outlining the eyes and darkening the lashes and eyebrows were achieved with a black paste called kohl, made from powdered antimony, burnt almonds, black oxide of copper, and brown clay ocher. The paste was stored in small alabaster pots and, moistened by saliva, was applied with ivory, wood, or metal sticks, not unlike a modern eyebrow pencil. Scores of filled kohl pots have been preserved.

Fashionable Egyptian men and women also sported history’s first

eye glitter

. In a mortar, they crushed the iridescent shells of beetles to a coarse powder, then they mixed it with their malachite eye shadow.

Many Egyptian women shaved their eyebrows and applied false ones, as did later Greek courtesans. But real or false, eyebrows that met above the nose were favored, and Egyptians and Greeks used kohl pencils to connect what nature had not.

Eye adornment was also the most popular form of makeup among the Hebrews. The custom was introduced to Israel around 850

B.C

. by Queen Jezebel, wife of King Ahab. A Sidonian princess, she was familiar with the customs of Phoenicia, then a center of culture and fashion. The Bible refers to her use of cosmetics (2 Kings 9:30): “And when Jehu was come to Jezreel, Jezebel heard of it; and she painted her face…” From the palace window, heavily made up, she taunted Jehu, her son’s rival for the throne, until her eunuchs, on Jehu’s orders, pushed her out. It was Jezebel’s cruel disregard for the rights of the common man, and her defiance of the Hebrew prophets Elijah and Elisha, that earned her the reputation as the archetype of the wicked woman. She gave cosmetics a bad name for centuries.

Rouge, Facial Powder, Lipstick: 4000

B.C

., Near East

Although Greek men prized a natural appearance and eschewed the use of most cosmetics, they did resort to rouge to color the cheeks. And Greek courtesans heightened rouge’s redness by first coating their skin with white powder. The large quantities of lead in this powder, which would whiten European women’s faces, necks, and bosoms for the next two thousand years, eventually destroyed complexions and resulted in countless premature deaths.

An eighteenth-century European product, Arsenic Complexion Wafers, was actually eaten to achieve a white pallor. And it worked—by poisoning the blood so it transported fewer red hemoglobin cells, and less oxygen to organs.

A popular Greek and Roman depilatory, orpiment, used by men and women to remove unwanted body hair, was equally dangerous, its active ingredient being a compound of arsenic.

Rouge was hardly safer. With a base made from harmless vegetable substances such as mulberry and seaweed, it was colored with cinnabar, a poisonous red sulfide of mercury. For centuries, the same red cream served to paint the lips, where it was more easily ingested and insidiously poisonous. Once in the bloodstream, lead, arsenic, and mercury are particularly harmful to the fetus. There is no way to estimate how many miscarriages, stillbirths, and congenital deformities resulted from ancient beautifying practices—particularly since it was customary among early societies to abandon a deformed infant at birth.

Throughout the history of cosmetics there have also been numerous attempts to prohibit women from painting their faces—and not only for moral or religious reasons.

Xenophon, the fourth-century

B.C

. Greek historian, wrote in

Good Husbandry

about the cosmetic deception of a new bride: “When I found her painted, I pointed out that she was being as dishonest in attempting to deceive me about her looks as I should be were I to deceive her about my property.” The Greek theologian Clement of Alexandria championed a law in the second century to prevent women from tricking husbands into marriage by means of cosmetics, and as late as 1770, draconian legislation was introduced in the British Parliament (subsequently defeated) demanding: “That women of whatever age, rank, or profession, whether virgins, maids or widows, who shall seduce or betray into matrimony, by scents, paints, cosmetic washes, artificial teeth, false hair, shall incur the penalty of the law as against witchcraft, and that the marriage shall stand null and void.”

It should be pointed out that at this period in history, the craze for red rouge worn over white facial powder had reached unprecedented heights in England and France. “Women,” reported the British

Gentlemen’s Magazine

in 1792, with “their wooly white hair and fiery red faces,” resembled

“skinned sheep.” The article (written by a man for a male readership) then reflected: “For the single ladies who follow this fashion there is some excuse. Husbands must be had…. But the frivolity is unbecoming the dignity of a married woman’s situation.” This period of makeup extravagance was followed by the sober years of the French Revolution and its aftermath.

By the late nineteenth century, rouge, facial powder, and lipstick—six-thousand-year-old makeup staples enjoyed by men and women—had almost disappeared in Europe. During this lull, a fashion magazine of the day observed: “The tinting of face and lips is considered admissible only for those upon the stage. Now and then a misguided woman tints her cheeks to replace the glow of health and youth. The artificiality of the effect is apparent to everyone and calls attention to that which the person most desires to conceal. It hardly seems likely that a time will ever come again in which rouge and lip paint will be employed.”

That was in 1880. Cosmetics used by stage actresses were homemade, as they had been for centuries. But toward the closing years of the century, a complete revival in the use of cosmetics occurred, spearheaded by the French.

The result was the birth of the modern cosmetics industry, characterized by the unprecedented phenomenon of store-bought, brand-name products: Guerlain, Coty, Roger & Gallet, Lanvin, Chanel, Dior, Rubinstein, Arden, Revlon, Lauder, and Avon. In addition—and more important—chemists had come to the aid of cosmetologists and women, to produce the first safe beautifying aids in history. The origins of brand names and chemically safe products are explored throughout this chapter.

Beauty Patch and Compact: 17th Century, Europe

Smallpox, a dreaded and disfiguring disease, ravaged Europe during the 1600s. Each epidemic killed thousands of people outright and left many more permanently scarred from the disease’s blisters, which could hideously obliterate facial features. Some degree of pockmarking marred the complexions of the majority of the European population.

Beauty patches, in the shapes of stars, crescent moons, and hearts—and worn as many as a dozen at a time—achieved immense popularity as a means of diverting attention from smallpox scars.

In black silk or velvet, the patches were carefully placed near the eyes, by the lips, on the cheeks, the forehead, the throat, and the breasts. They were worn by men as well as women. According to all accounts, the effect was indeed diverting, and in France the patch acquired the descriptive name

mouche

, meaning “fly.”

Patch boxes, containing emergency replacements, were carried to dinners and balls. The boxes were small and shallow, with a tiny mirror set in the lid, and they were the forerunner of the modern powder compact.