Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things (32 page)

Read Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things Online

Authors: Charles Panati

Tags: #Reference, #General, #Curiosities & Wonders

Two-wheeled handcarts were known throughout the East and West as early as 1000

B.C

., but it appears that the need never arose, as it did in China in Liang’s time, to construct a one-wheeled device to traverse a severely narrow track of ground.

From transporting military supplies, the Chinese wheelbarrow was used to remove dead and wounded soldiers from battlefields. Then it was enlarged and slightly modified to carry civilians about town, with a capacity to accommodate about four adults or six children at a time. These larger wheelbarrows were usually pulled by a donkey and guided from behind by a driver.

The Chinese had two poetically descriptive names for the wheelbarrow: “wooden ox” and “gliding horse.” Commenting on the mechanical advantage of the device for a load of given weight, a fifth-century historian wrote: “In the time taken by a man to go six feet, the Wooden Ox would go twenty feet. It could carry the food supply for one man for a whole year, and yet after twenty miles the porter would not feel tired.”

The European wheelbarrow originated during the Middle Ages. Whereas the Chinese wheelbarrow had its single wheel in the center, directly under the load, so that the pusher had only to steer and balance it, the European version had the wheel out in front. This meant that the load was supported by both the wheel and the pusher.

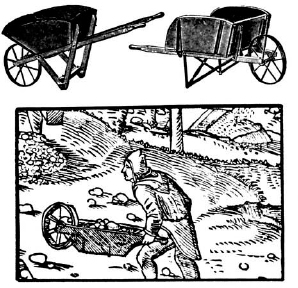

Mortar wheelbarrow and garden variety c. 1880. Woodcut of medieval laborer transporting stones in a Western-style wheelbarrow

.

Historians believe that the European invention was an adaptation of an earlier vehicle, the hod, a wooden basket suspended between two poles and carried in front and back by two or four men. Somewhere around the twelfth century, an anonymous inventor conceived the idea of replacing the leading carriers by a single small wheel; thus, the Western wheelbarrow was created.

The European wheelbarrow was not as efficient as the Chinese. Nonetheless, workmen building the great castles and cathedrals on the Continent suddenly had a new, simple device to help them cart materials. Most manuscripts from the twelfth to the fifteenth centuries that contain illustrations of wheelbarrows invariably show them loaded with bricks and stones, in the service of builders. In this respect, the European wheelbarrow’s function was quite different from that of the Chinese version. And indeed, the forward placement of the wheel meant that a man using the European wheelbarrow had to lift a large portion of the load, besides pushing and balancing it. Thus, unlike the Chinese invention, the Western wheelbarrow was unsuited for carrying a burden over long distances. Consequently, it never became a vehicle for human transportation.

Until the seventeenth century, when frequent trading began between Europe and China, each had its own distinct form of wheelbarrow. But then European traders to the Orient returned with astonishing tales of the loads that could be carried effortlessly over long distances with the Chinese wheelbarrow. That design began to appear in Western countries. Today both models are available, depending on individual work requirements.

For the Nursery

Fairy Tales: 16th Century, Italy and France

Rape, child abuse, and abandonment are the stuff of contemporary headlines and feature films. But they are also themes central to many of our most beloved fairy tales—as they were originally conceived.

The original “Sleeping Beauty” does not end happily once the princess is awakened with a kiss; her real troubles just begin. She is raped and abandoned, and her illegitimate children are threatened with cannibalism. And in the authentic version of “Little Red Riding Hood,” the wolf has yet to digest the grandmother when he pounces on Red, ripping her limb to limb. Many artists of the day, believing that the two violent deaths were too much for children to endure, refused to illustrate the tale. To make it more palatable, one illustrator introduced a hunter, who at the last minute slays the wolf, saving at least Little Red.

In the present century, numerous critics continue to argue that many fairy tales and nursery rhymes read to children—and repeated by them—are quintessentially unsavory, with their thinly veiled themes of lunacy, drunkenness, maiming of humans and animals, theft, gross dishonesty, and blatant racial discrimination. And the stories do contain all these elements and more—particularly if they are recounted in their original versions.

Why did the creators of these enduring children’s tales work with immoral and inhumane themes?

One answer centers around the fact that from Elizabethan times to the early nineteenth century, children were regarded as miniature adults. Families were confined to cramped quarters. Thus, children kept the same late

hours as adults, they overheard and repeated bawdy language, and were not shielded from the sexual shenanigans of their elders. Children witnessed drunkenness and drank at an early age. And since public floggings, hangings, disembowelments, and imprisonment in stocks were well attended in town squares, violence, cruelty, and death were no strangers to children. Life was harsh. Fairy tales blended blissful fantasy with that harsh reality. And exposing children to the combination seemed perfectly natural then, and not particularly harmful.

One man more than any other, Charles Perrault, is responsible for immortalizing several of our most cherished fairy tales. However, Perrault did not originate all of them; as we’ll see, many existed in oral tradition, and some had achieved written form. “Sleeping Beauty,” “Cinderella,” and “Little Red Riding Hood” are but three of the stories penned by this seventeenth-century Frenchman—a rebellious school dropout who failed at several professions, then turned to fairy tales when their telling became popular at the court of King Louis XIV.

Charles Perrault was born in Paris in 1628. The fifth and youngest son of a distinguished author and member of the French parliament, he was taught to read at an early age by his mother. In the evenings, after supper, he would have to render the entire day’s lessons to his father in Latin. As a teenager, Perrault rebelled against formal learning. Instead, he embarked on an independent course of study, concentrating on various subjects as mood and inclination suited him. This left him dilettantishly educated in many fields and well-prepared for none. In 1651, to obtain a license to practice law, he bribed his examiners and bought himself academic credentials.

The practice of law soon bored Perrault. He married and had four children—and the same number of jobs in government. Discontent also with public work, he eventually turned to committing to paper the fairy tales he told his children. Charles Perrault had found his métier.

In 1697, his landmark book was issued in Paris. Titled

Tales of Times Passed

, it contained eight stories, remarkable in themselves but even more noteworthy in that all except one became, and remained, world renowned. They are, in their original translated titles: “The Sleeping Beauty in the Wood,” “Little Red Riding Hood,” “Blue Beard,” “The Master Cat: or Puss in Boots,” “Diamonds and Toads,” “Cinderella: or, The Little Glass Slipper,” and “Hop o’ my Thumb.” The eighth and least famous tale, “

Riquet à la Houppe

,” was the story of a deformed prince’s romance with a beautiful but witless princess.

Perrault did more than merely record stories that were already part of popular oral and written tradition. Although an envious contemporary criticized that Charles Perrault had “for authors an infinite number of fathers, mothers, grandmothers, governesses and friends,” Perrault’s genius was to realize that the charm of the tales lay in their simplicity. Imbuing them with magic, he made them intentionally naive, as if a child, having heard the

tales in the nursery, was telling them to friends.

Modern readers, unacquainted with the original versions of the tales recorded by Perrault and others, may understandably find them shocking. What follows are the origins and earliest renditions of major tales we were told as children, and that we continue to tell our own children.

“Sleeping Beauty”: 1636, Italy

“The Sleeping Beauty in the Wood” was the opening tale in Charles Perrault’s 1697 book. It is the version we still tell today, but it did not represent the complete original story; Perrault’s recounting omits many of the beautiful princess’s horrifying ordeals. The first written version of the tale was published in Italy in 1636 by Giambattista Basile in his collection

Pentamerone

.

In this Neapolitan “Sleeping Beauty,” a great king is forewarned by wise men that his newborn daughter, Talia, is in peril from a poison splinter in flax. Although the king bans flax from the palace, Talia, as a young girl, happens upon a flax-spinning wheel and immediately catches a splinter beneath her fingernail, falling dead.

Grief-stricken, the king lays his daughter’s body on a velvet cloth, locks the palace gates, and leaves the forest forever. At this point, our modern version and the original diverge.

A nobleman, hunting in the woods, discovers the abandoned palace and the insensate body of the princess. Instead of merely kissing her, he rapes her and departs. Nine months later, the sleeping Talia gives birth to twins, a boy and a girl. Named Sun and Moon, they are looked after by fairies. One day, the male infant sucks on his mother’s finger and the poisonous splinter is dislodged, restoring Talia to consciousness.

Months pass, and the nobleman, recollecting his pleasurable encounter with the fair-haired sleeping beauty, revisits the palace and finds her awake. He confesses to being the father of Talia’s children, and they enjoy a week-long affair before he leaves her again—for his wife, whom he conveniently never mentions.

The original story at this point gets increasingly, if not gratuitously, bizarre. The nobleman’s wife learns of her husband’s bastard children. She has them captured and assigns them to her cook, with orders that their young throats be slashed and their flesh prepared in a savory hash. Only when her husband has half-finished the dish does she gleefully announce, “You are eating what is your own!”

For a time, the nobleman believes he has eaten his children, but it turns out that the tenderhearted cook spared the twins and substituted goat meat. The enraged wife orders that the captured Talia be burned alive at the stake. But Sleeping Beauty is saved at the last moment by the father of her children.

Little Red Riding Hood and the Wolf. A gentle 1872 depiction of a gory tale

.

“Little Red Riding Hood”: 1697, France

This tale is the shortest and one of the best-known of Perrault’s stories. Historians have found no version of the story prior to Perrault’s manuscript, in which both Granny and Little Red are devoured. The wolf, having consumed the grandmother, engages Red in what folklorists claim is one of the cleverest, most famous question-and-answer sequences in all children’s literature.

Charles Dickens confessed that Little Red was his first love, and that as a child he had longed to marry her. He later wrote that he bitterly deplored “the cruelty and treachery of that dissembling Wolf who ate her grandmother without making any impression on his appetite, and then ate her [Little Red], after making a ferocious joke about his teeth.”

In fact, many writers objected to Perrault’s gruesome ending and provided their own. In a popular 1840 British version, Red, about to be attacked by the wolf, screams loudly, and “in rushed her father and some other faggot makers, who, seeing the wolf, killed him at once.”

During that same period, French children heard a different ending. The wolf is about to pounce on Red, when a wasp flies through the window and stings the tip of his nose. The wolf’s cries of pain alert a passing hunter, who lets fly an arrow “that struck the wolf right through the ear and killed him on the spot.”

Perhaps the goriest of all versions of the tale emerged in England at the end of the nineteenth century. This popular telling concludes with the wolf collecting the grandmother’s blood in bottles, which he then induces the unsuspecting Red to drink. It is interesting to note that while all the revisions endeavor to save Red, none of them spares the grandmother.