Extortion (19 page)

Authors: Peter Schweizer

During the critical week before MF Global declared bankruptcy, and as funds were being shifted around, Commodity Futures Trading Commission chairman Gary Gensler was in regular contact with MF Global executives through a personal and private email account. The CFTC inspector general later would report that this was “troubling.”

18

Clearly, this was not the sort of cozy arrangement other financial entities could expect to receive.

When MF Global filed for bankruptcy on October 31, 2011, over 99 percent of its customer accounts were commodity accounts. But federal regulators decided that the Securities Investor Protection Corporation (SIPC) would take over the liquidation. The CFTC should have been in charge, but Gary Gensler deferred to the SEC. This allowed MF Global Holdings to file a chapter 11 bankruptcy, enabling the firm to continue to transfer assets in and out of accounts. Had it been designated by regulators as a commodities firm (which it was), those accounts would have been frozen to protect customers.

19

The CME Group is a diverse derivatives marketplace comprising five designated contract markets (CME, CBOT, NYMEX, COMEX, and KCBT). The CME Group was the “primary regulator” of MF Global. CME Group chairman Terry Duffy told a congressional committee that Corzine and MF Global executives knew they were raiding customer accounts to cover trading shortfalls. But then something interesting happened: the “primary regulator” was instructed by government officials to end its MF Global investigation. The CME Group had been focusing its regulatory investigation on the illegal raiding of customer accounts. As journalist and futures expert Mark Melin puts it:

As documented on page 139 of the Trustees’ report, on October 28, Mr. Corzine was faced with a decision. He was required to cover an internal margin call of $175 million in London with his only source of funding which was customer assets. It is at this moment, a willful decision to transfer customer funds to cover business expenses took place, which violated the law. This was said to be one of the clear focuses of a CME Group Investigation.

20

So, despite Corzine having bundled at least $500,000 for the Obama campaign, the president’s DOJ still charged him, right? Wrong. Industry observers were stunned when newspaper accounts quoted government regulators and law enforcement officials on background as saying that the “case was cold,” even before MF Global executives had been questioned by authorities.

21

By August 2012, the

New York Times

was reporting that the criminal investigation was winding down, with no charges expected.

22

Legal observers were stunned that Edith O’Brien, the MF Global executive who was responsible for executing so many of the questionable trades, was neither charged nor granted immunity.

One might think that commodities traders would circle the wagons and defend the actions of Corzine and MF Global. After all, wouldn’t that be to their own benefit? But that has hardly been the case. As futures trader Stanley Haar puts it, “If the crimes committed in this case are allowed to go unpunished . . . this will only serve to reinforce the widespread perception of pervasive cronyism and corruption in Washington, D.C.”

23

Lisa Timmerman, a seventeen-year employee of MF Global who was the firm’s assistant comptroller for five years, is more blunt: “Corzine is a major Obama fundraiser [which] is keeping prosecutors from bringing criminal charges against him.”

24

On June 27, 2013, the CFTC filed a civil complaint against Corzine that, among other things, he unlawfully used customer funds.

25

However, neither Jon Corzine nor any other MF Global employee has been criminally charged. What’s more, neither Corzine nor any of the senior executives have been barred from trading in the futures markets. In fact, the

New York Post

reported that the criminal probe into Jon Corzine is now being dropped, according to a person knowledgeable of the probe.

26

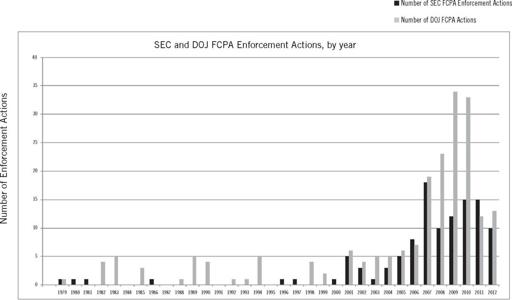

In recent years, the law of choice for legal extortion and intimidation has been the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA). It was originally passed in 1977 in the shadow of Watergate, following investigations that revealed that U.S. corporations had been bribing foreign government officials in exchange for government contracts. In 1976, for example, Japanese prime minister Tanaka Kakuei was indicted after it was revealed that he received $2 million in cash from Lockheed Martin in exchange for arranging a large government contract.

27

The FCPA is narrowly focused, or at least it appears to be. The law includes a bribery provision that requires a showing that the payment was “knowingly” made.

28

But a second provision of the law, the so-called record-keeping provision, holds that if you make “false or misleading statements on a company’s books for any purpose whatsoever” involving money paid overseas, you could face a fine or even imprisonment. Furthermore, if you make legitimate “facilitating payments” but fail to account for them, you could face jail time—even if there is no evidence that bribery ever took place.

29

Into such ambiguous cracks, extortion can fall. The penalties in the law are steep: not only could a company and its executives pay steep fines, but executives, officers, directors, shareholders, and employees could face jail time. In some cases, a jail term could be as long as twenty years.

30

Professor Mike Koehler, the most widely published legal scholar on FCPA, notes that Congress “specifically intended for its anti-bribery provisions to be narrow in scope.”

31

At first, after the law was enacted in 1977, “enforcement was largely non-existent for most of its history.”

32

On average, only two to three cases a year were pursued during the law’s first thirty years. Then suddenly, within the past decade, enforcement of the law exploded. The results: it is one of the most profitable and aggressive forms of legal extortion in American history.

Shortly after Barack Obama was elected president in 2008, he appointed a team of experienced white-collar criminal defense attorneys to head up the Department of Justice. Eric Holder, the co-chair of his campaign, got the top job of attorney general. Holder had been head of the Washington office of Covington & Burling, a powerful D.C. white-shoe law firm. Joining him from Covington was Lanny Breuer, who became head of the Criminal Division. Steven Fagell, also of Covington, came over to serve as the deputy chief of staff and counselor to Breuer. Jim Garland moved over to serve as counselor and deputy chief of staff to Holder.

In early 2009, the United States was grappling with the financial crisis and the mortgage-backed securities implosion. While many people argued about real criminal conduct on the part of some investment bankers, mortgage companies, and others in the financial sector, Breuer’s interest seemed to be elsewhere. When he took over as head of the DOJ’s 900-lawyer Criminal Division, “the substantive law most of interest” to him proved to be . . . the FCPA.

33

Early on, he expressed his view that FCPA was one of his “top priorities.”

34

Breuer’s and Holder’s interest in the anticorruption law is curious because of Covington’s role in actually drafting the bill. (The firm

USING THE LEGAL SYSTEM TO EXTORT

35

Source:

www.sec.gov/spotlight/fcpa/fcpa-cases.shtml

and

http://www.justice.gov/criminal/fraud/fcpa/cases/2013.html

.

brags on its website that “Covington lawyers have a unique command of anti-corruption laws, in part due to our role in helping draft the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of 1977.”

36

) While at Covington & Burling, Holder and Breuer were both listed as “senior FCPA lawyers” (in a May 9, 2008, email alert sent out by Covington—entitled “FCPA-2007 Enforcement Trends”—that noted that Holder and Breuer “represent corporations before the DOJ, SEC and other government agencies, conducting internal investigations and developing corporate anti-corruption compliance programs”). At that time, anticorruption services were hardly a big business for Covington. FCPA enforcement cases were on the rise, but still relatively rare. Holder, Breuer, and their fellow attorneys at Covington were about to change that, radically expanding the scope of the law while aggressively using it as a tool to increase the demand for their own services and very possibly as a tool of political intimidation.

In 2009, according to the DOJ’s Criminal Division, there were at least 120 companies subject to FCPA investigations.

37

A special unit was set up in the FBI to investigate FCPA cases. The SEC also set up a specialized unit, and it became a top priority for the Obama Department of Justice.

38

Breuer bragged in November 2010 that the law’s “enforcement is stronger than it’s ever been—and getting stronger.”

39

Legal scholars and professionals who tracked the law were befuddled. Why the sudden explosion of antibribery investigations coming out of Washington? One professor wrote about the SEC’s “unexplained aggressive enforcement” that was taking place.

40

Another noted that “FCPA enforcement in recent years has expanded across almost every conceivable dimension.”

41

One law professor expressed concern about the “recent radicalization of [FCPA] enforcement. . . . In short, the way the Act has been enforced lately has transformed the substantive law and shaken the business world.”

42

The sort of cases that were being pursued and prosecuted bore little relationship to the bribery of foreign government officials to procure government contracts. Holder and Breuer were now charging companies and individuals “not alleged to have engaged in or even known about the wrongdoing.”

43

The Justice Department cast a remarkably wide net that included expansive definitions of what a “government official” was and what constituted a “bribe.” How wide? Lanny Breuer admitted that essentially no company was immune from charges of misconduct, given the new standard. “There will always be rogue employees who decide to take matters into their own hands,” he said. “They are a fact of life.”

44

Ignorance of what a midlevel employee or overseas consultant might be doing was no defense. Large corporations were charged because they “directly or indirectly” gave gifts to overseas individuals. These gifts didn’t need to be cash bribes. Offering “sightseeing trips” could get you into legal trouble.

45

A large pharmaceutical company made a contribution to a legitimate charity in Poland, but was charged with wrongdoing because it had not accurately reflected the contribution in its financial statements.

46

Royal Dutch Shell was charged with conspiracy to violate the antibribery law based “solely on the allegations that [its] express door-to-door courier service” offering expedited delivery into Nigeria paid money to Nigerian customs officials so equipment could be delivered quickly. Yet even if the company didn’t know about the payments, it was deemed to have received an “improper advantage” in the African country.

47

These were not exactly traditional examples of bribery. There were no large cash payments to government ministers or luxury sports cars purchased for a midlevel bureaucrat. Now firms were facing possible criminal charges for giving such gifts to overseas individuals as “bottles of wine, watches, cameras, kitchen appliances, business suits, television sets, laptops, tea sets, and office furniture.” Pharmaceutical companies that offered even very small gifts to a physician, nurse, or midwife might now face criminal prosecution under the Justice Department theory that these health care workers are “government officials.”

48

A former assistant chief of the DOJ Fraud Section noted that “some of the government’s cases appear to blur the lines or muddy the waters when it comes to the limits of the statute.”

49

That was putting it mildly.