Read Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure Online

Authors: Tim Jeal

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Adventure, #History

Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure (56 page)

So it seemed that Mackinnon was finally to get what he had asked for all along and the ‘legacy’ of the Nile explorers Speke, Grant, Baker and Stanley would be saved for Britain. Another way of looking at the Heligoland Treaty was that two

European nations had traded a minuscule rocky island in the North Sea for a vast chunk of Africa without reference to the people who lived there. For Mackinnon and Stanley however, Mwanga’s participation in the slave trade, his murder of Bishop Hannington, and the mutilation and roasting alive of scores of mission converts seemed more than sufficient justification for intervention.

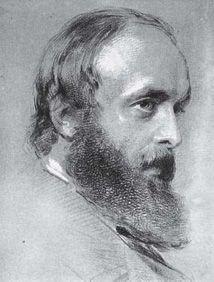

Lord Salisbury

Yet in nineteenth-century Africa, few arrangements made in distant places went smoothly, even when a British prime minister and a crowned German head of state had decreed they should. In reality the situation in Buganda remained remarkably volatile, even after the removal of the immediate German threat. Buganda’s capital, Kampala, was a thousand miles from the coast, and Mackinnon, whose Imperial British East Africa

Company was close to bankruptcy, was nevertheless being asked to gain control of the kingdom as quickly as possible.

To achieve this, the shipping mogul and his directors sent to Central Africa Captain Frederick Lugard, an intense, dark-eyed young Indian Army officer with a floppy black moustache and a fondness for crumpled light-weight khaki uniforms. He had the classic background for a successful African adventurer, having been jilted by an adored fiancée, whom he had caught in bed with another man. So where better than Africa to re-establish his manly credentials? This he had started to do near Lake Nyasa in 1888, where he had fought bravely and been wounded while saving missionaries from death at the hands of Arab slave traders.

On arriving in Kampala at the end of 1890, Lugard found that Mwanga’s sympathies lay with the powerful faction of chiefs supporting the French missionaries. So, on their advice the

kabaka

refused to sign a treaty with Lugard. After all, why should he allow any outsider to limit his powers as hereditary ruler of Buganda and take away his right to wage war, buy gunpowder and trade in slaves?

4

Only Lugard’s small but disciplined force, and his Maxim gun, eventually persuaded Mwanga that he had no choice but to sign. This was not the first time that disaster had befallen the

kabaka.

The Muslims had long ago curtailed his independence, and the rivalry of the French and British missionaries and their African factions had caused a civil war in his kingdom that had driven him briefly into exile.

Shortly after curtailing Mwanga’s powers, Lugard beat back a Muslim incursion into Buganda from Bunyoro. Nevertheless, the worsening antagonism between the supporters of the Catholic Mission, the Fransa, and of the Protestant Mission, the Inglesa, presented him with a more serious problem, especially since Mwanga was encouraging the Fransa to assert themselves militarily. Knowing that his men and the British mission’s supporters were outnumbered by the French alliance with Mwanga, Lugard strengthened the position of Mackinnon’s company by marching to Lake Albert and recruiting 200 of the Sudanese troops left there by Emin Pasha. Lugard was back in

Buganda in December 1891 and found that relations between the missions had worsened. A return to civil war seemed inevitable, with the British mission and their Bugandan adherents likely to be on the losing side. So Lugard was horrified on his return to find a letter from the directors informing him that the company was insolvent and that he must withdraw. With Lord Salisbury’s majority in the Commons now down to four, and the Liberals and Irish MPs invariably voting against every Tory motion advocating government backing for a railway line to Uganda, there seemed no chance that Mackinnon’s company would be making any profits in the foreseeable future.

5

But rather than endanger the lives of the Protestant missionaries and their Inglesa converts by obeying the order to quit, Lugard vowed to stay on until a shortage of ammunition and other supplies forced him to pull out. Before that happened, some emergency fund-raising in Britain by supporters of the Church Missionary Society enabled the young officer to cling on in Buganda.

Then, on 22 January 1892, coincidentally Captain Lugard’s thirty-fourth birthday, one of the Fransa chiefs who supported the French White Fathers murdered an Inglesa convert. The crime was committed in Mengo, close to the

kabaka

’s palace, and the body was left out in the sun all day. Lugard climbed the hill and demanded that the

kabaka

hand over the murderer so he could be tried and, if found guilty, executed by firing squad. Instead, Mwanga released the arrested Fransa on the grounds that he had acted in self-defence. Then the French priests incited their flock to violence by telling them that Lugard was merely the representative of a trading company and ‘could be driven out with sticks’.

6

They denounced the Scottish Protestants as heretics, and refused to tell their flock to disband and disarm as Lugard asked them to do. Their leader, Monsignor Jean-Joseph Hirth, warned Captain Lugard that the French nation was watching events in Buganda very closely.

Lugard feared that unless he could force Mwanga to hand over the murderer, the

kabaka

and the Fransa would take it as

a sign of weakness and be encouraged to attack the Inglesa and the company’s men. Lugard sent Dualla, his trusted diplomat and interpreter (formerly Stanley’s most valued assistant on the Congo) to warn Mwanga to comply or prepare for war with the company. Flanked by Fransa chiefs, Mwanga told Dualla that he and his allies would never give up the accused man and were ready to fight.

7

Hearing this, Lugard armed all his porters as well as his servants and soldiers. Even so, he was considerably outnumbered, although to compensate his 200 Sudanese soldiers were armed with modern Sniders, and he had a Maxim gun. A second Maxim had recently come up from the coast but was not in working order.

On 24 January, Lugard fixed his binoculars on the straggling lines of Fransa and Inglesa colliding in the valley between the lush hills of Rubago and Mengo. Some of the Fransa were waving an immense tricolour. Rather than let the Protestant Scots and their followers be defeated, Lugard deployed his one functioning Maxim with predictable results. The Fransa and the French missionaries fled in terror towards Bulingugwe Island. Then they declined Lugard’s well-intended invitation to them to return to Mengo and begin negotiating peace terms. The

kabaka

’s rejection of this offer was a tragic mistake. Lugard ordered his second-in-command, Captain Ashley Williams, to take a detachment of Sudanese troops and his one functioning Maxim to drive them from the island. In the ensuing fight a hundred people lost their lives (many being drowned) and Mwanga fled into exile with the majority of his Catholic supporters.

8

An understandably emotional version of events was sent to Paris by Monsignor Hirth where it aroused passionate indignation. In London, Lord Salisbury and the British press played down the incident, and defended Lugard from allegations of bad faith and brutality. It would turn out that no French missionary had been killed.

9

Soon after these events Lugard sent emissaries to invite Mwanga to return to Kampala, which he did on 30 March 1892, signing a treaty several days later. This would mark the end of Buganda’s independence. The various offices of state

were removed from the

kabaka

’s gift and shared out by Lugard between the religious groups, including the Muslims. Control of different parts of the country also passed to the factions, with the Protestants being treated most favourably. Yet, at this moment of apparent triumph for Lugard and Mackinnon, Lord Salisbury lost his slender majority in the House of Commons, and Mr Gladstone was invited by Queen Victoria to form a government.

The Grand Old Man was wholly against making Buganda and wider Uganda a British protectorate. He knew that to enlarge the British Empire, while he was seeking to give Home Rule to the Irish, would be wholly inconsistent. Sir William Harcourt, the new Chancellor of the Exchequer, agreed. By now Lugard was on his way home, determined to fight tooth and nail to ensure that Uganda became British rather than French, which would be its destiny if Gladstone and Harcourt were to have their way. He told Sir Gerald Portal, the newly appointed British Consul General at Zanzibar, that there would be a bloodbath if the government refused to help the Imperial British East Africa Company to stay in Uganda beyond the end of 1892. The Arabs would return, he predicted, and, in alliance with the French, would fall upon the British missionaries and the Inglesa. Portal obligingly cabled to Lord Rosebery, the new Foreign Secretary, stating that withdrawal of the company would ‘

inevitably

result in a massacre of Christians such as the history of this country cannot show’. This communication did not impress Gladstone and Harcourt, who saw no reason to get sucked into a country stuffed with warring factions, where ‘endless expense, trouble and disaster’ looked to be the most likely reward for intervention.

10

As soon as Lugard arrived in London, the question whether Britain should retain or abandon Uganda was fiercely debated up and down the country. The young army officer was joined by the veteran explorer, Henry Stanley, in numerous town halls and chambers of commerce. Again and again they asked whether the nation was to be denied a unique opportunity to increase its trade in coffee, cotton, ivory and resins simply because the government lacked the vision and courage to annexe Uganda.

Meanwhile the Church Missionary Society and its supporters organised petitions, urging people to support the company and save the Protestant missionaries from the Muslims and the Catholics.

The Liberal cabinet failed to agree how to respond to the clamour being got up in the press. The octogenarian Prime Minister was implacably opposed to colonial advances in Africa, for moral as well as practical reasons, but Lord Rosebery, his youthful Foreign Secretary and heir apparent, led the wing of the party known as the Liberal Imperialists, whose members favoured progressive policies at home but imperial advances abroad. Rosebery took the same line as Lord Salisbury on the need to secure the Nile’s sources for Egypt’s sake, and listened sympathetically to Lugard’s dire predictions of a massacre of Protestants by Muslims, and a subsequent French take-over if the company withdrew. Rosebery warned his colleagues of the political consequences of allowing the missionaries to come to harm. It would be as damaging to the Liberals as had been their failure to aid General Gordon. Sir William Mackinnon – recently rewarded with a baronetcy by Lord Salisbury for keeping out the Germans – orchestrated a national ‘Save Uganda’ campaign, and although Harcourt mocked his efforts as ‘the whole force of Jingoism at the bellows’, the Liberal cabinet was being torn apart from within.

11

In order to stop Rosebery resigning, the anti-Imperialists in the cabinet were obliged, against all their instincts, to grant Mackinnon’s company a subsidy enabling it to remain in Uganda until the end of March 1893, and to send Sir Gerald Portal, who had already made his support for Lugard abundantly clear, as their commissioner to report on Uganda’s future. Secretly, Rosebery told Portal to prepare to take over the country from the company. When Portal eventually sent in his report, it predictably contained a recommendation that the government should revoke the company’s charter and place Uganda under the supervision of the British state. In addition, he advised that a railway should be built from the coast to Lake Victoria.

12

Gladstone had surrendered to Rosebery over Uganda in the hope of remaining in power long enough to realise his dream of bringing Home Rule to Ireland. But age and infirmity, and the new imperialism against which he had fought so resolutely, brought about his resignation in March 1894 – the resigning issue being his cabinet colleagues’ readiness to increase expenditure on new battleships (it could just as well have been Uganda). Five weeks after the Grand Old Man returned to private life, Rosebery informed both Houses of Parliament that Uganda would not be abandoned. It was declared a protectorate on 27 August 1894, with Equatoria being incorporated as its immense northern province. The tide seemed finally to have turned against the old mid-Victorian Liberal policies of isolation, free trade and

laissez-faire.

With Lord Salisbury’s return to power in 1895 a harder more competitive era in foreign affairs had dawned.

As yet the immense territory of the Sudan and its uncharted south had not become the focus of the world’s attention, as Uganda and Equatoria had just been. Speke, Grant, Baker, Gordon and his officers, had all criss-crossed this immense hinterland between Buganda and Khartoum, which seemed to offer to any European nation daring enough to grab it, the opportunity to control the Nile, despite the advantage enjoyed by Britain as the possessor of the Ugandan source. Gladstone and Lord Salisbury had ignored the whole region even after the humiliation of Gordon’s death, but events would soon bring about a change of heart. The ownership of the Nile from source to sea was about to become the focus of renewed competition.