Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure (41 page)

Read Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure Online

Authors: Tim Jeal

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Adventure, #History

Entering Ujiji on 10 November 1871,

24

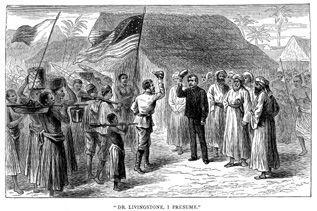

Stanley’s men fired repeated volleys – the usual ritual when a caravan entered a town – and he ordered the Stars and Stripes to be unfurled and borne aloft at the head of the column. An animated crowd surged around the advancing newcomers, and Susi, one of Livingstone’s longest-serving followers, greeted Stanley ecstatically, and then ran off shouting: ‘An Englishman coming! I see him!’

25

Approaching Livingstone’s house, Stanley felt so excited that he longed ‘to vent [his] joy in some mad freaks, such as idiotically biting [his] hand, or turning a somersault’.

26

He clambered down from his donkey’s back, and saw, standing only a few paces away, a man of about sixty with a grey beard. He was wearing an old red waistcoat and tweed trousers.

This

was the scarcely imaginable moment that he had nevertheless dreamed about ever since making his impossible prediction to

Lewis Noe five years earlier. He knew that he would be famous now for the rest of his life and possibly rich too. But he had not the faintest premonition of the immeasurably more important consequences which would spring from this extraordinary meeting, affecting himself and even the history of Africa.

The meeting in the famous engraving in Stanley’s book

How I Found Livingstone

.

TWENTY

The Doctor’s Obedient and Devoted Servitor

At the point in Stanley’s diary where he advances towards Livingstone, three pages have been torn out, just where he ought to be saying: ‘Dr Livingstone, I presume?’ The only reason for tearing them out would seem to be because they had not confirmed the words of the famous greeting. Nor is the historic question to be found in Livingstone’s diary, or in his notebooks, or in any of the dozen or so letters he wrote during the next couple of weeks.

1

Because Livingstone repeated Susi’s far less memorable words in most of his contemporary letters, the greeting would appear to have been invented by Stanley at some point during the six months that followed the meeting. Indeed, ever since leaving Zanzibar he had been trying to work out what laconic, understated greeting an English gentleman would be likely to come up with on such a momentous occasion. With ‘Dr Livingstone, I presume?’ he believed he had finally found the perfect formulation. It would be a great shock when people laughed at him for not managing to say something heartfelt and spontaneous.

2

In his book

How I Found Livingstone,

Stanley’s second remark to Livingstone is recorded as having been: ‘I thank God I have been permitted to see you.’ And this, or some more colloquial variant, seems more likely to have been spoken.

3

But whatever was said, there can be no doubt at all that Livingstone had never been so pleased to see a white face as he was to see Stanley’s. He was not exaggerating when he said: ‘You have brought me new life.’

4

So the moment was one of high emotion for both men. Stanley knew from the tears in Livingstone’s eyes that there was no possibility he might refuse to answer his questions. But Stanley

waited till the following day before admitting that he was a special correspondent of the

New York Herald.

‘That despicable paper,’ Livingstone called it, but with a smile.

5

Stanley soon grasped that the doctor was Scottish, not English as he had at first thought, and that they shared a Celtic background – though Stanley would continue to represent himself as an American.

When he described Livingstone’s appearance as ordinary, ‘like a book with a most unpretending binding’, he put his finger on an important truth about the man. His appearance gave ‘no token of what element of power or talent lay within’.

6

He looked younger than his actual age of nearly sixty; his eyes were brown and very bright; his teeth loose and irregular; his height average; shoulders a little bowed, and he walked with ‘a firm but heavy tread, like an overworked or fatigued man’.

7

At once Stanley sensed that Livingstone was not the misanthrope Kirk had made him out to be. Few childhoods could rival his own for suffering and deprivation, but Livingstone’s had been no picnic either. He had been a child factory worker in a cotton mill near Glasgow, and had lived with his family of six in a single room in a tenement block. Yet he had managed to put himself through medical school on his earnings as a cotton spinner.

Livingstone had first sailed for Africa in 1841 – the year of Stanley’s birth – and had spent ten frustrating years as a medical missionary in Botswana, having been ordained a Congre-gationalist minister before leaving England. Despite the public’s view of him as an unequalled missionary, in reality he made but one convert, who lapsed. After this failure, he had not been prepared to spend a lifetime as his father-in-law had done, converting a few dozen people. Livingstone understood very well why Africans considered monogamy and small families a threat to their entire way of life. A chief with many wives could give great feasts, grow large quantities of food and enjoy the support of many descendants. Why would he wish to throw this away? Failure as a conventional missionary led Livingstone to believe that only massive cultural intrusion could lead Africans to adopt the white man’s customs and religion in any numbers. If traders

could come up rivers into the interior in steamships, and build two-storey houses, and sell factory goods in exchange for local produce, Africans might become more respectful towards the beliefs of people who could bring them such wonders. In time, Africans might even consent to work for wages, have smaller families, limit themselves to a single wife, and consequently their loyalty to chief and tribe might weaken enough to give Christianity a chance.

8

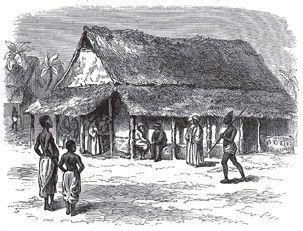

Livingstone sitting with Stanley outside his

tembe

in Ujiji (from

How I Found Livingstone).

So between 1849 and 1851, Livingstone had made three journeys aimed at opening up the continent, culminating in his trek to the Zambezi, which he had reached near Linyanti on 4 August 1851. Between 1853 and 1856, he crossed Africa from coast to coast, along the line of the Zambezi. Next, between 1859 and 1864, he tried to prove its navigability and find a location in South Central Africa suitable for missionaries and

traders to settle in. Rivers would, he hoped, be ‘God’s Highways’ into the interior.

9

But the Zambezi was choked with sandbars and blocked by rapids, which combined with malaria to destroy his dreams of a settlement. Yet rivers and lakes still lured him powerfully, as he discovered when Speke’s and Burton’s rival Nile theories gripped his imagination.

Normally secretive about his geographical discoveries, Livingstone paid Stanley the immense compliment of confiding to him all his ideas about the Nile’s source, and then, just four days after the younger man’s arrival, the older man suggested that he travel with him to the Lualaba to help him finish his work. Stanley was torn, but in the end declared that he had to do his duty to the

New York Herald

and hurry to the coast with his news of the meeting.

10

Yet, two days later, Stanley, who had hated refusing the doctor, suggested a compromise: they should travel instead to the infinitely more accessible northern end of Lake Tanganyika. From reading the published

Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society,

Stanley had been aware since 1865 of Burton’s claim that the River Rusizi flowed northwards out of Lake Tanganyika into the southern end of Baker’s Lake Albert before continuing northwards as the White Nile. This view was shared by Livingstone, as Stanley already knew from the RGS’s publication of the doctor’s letter to John Kirk of 30 May 1869. In this letter (the last to reach the outside world before Stanley reached Ujiji) Livingstone had said that he needed to ‘go down’, what he called ‘the [Nile’s] eastern line of drainage’, by which he meant the northward-flowing river system beginning with Lake Bangweulu, and flowing on north, via Lake Moero, into the west side of Lake Tanganyika, and continuing via the Rusizi into Lake Albert.

11

But after learning more about the great Lualaba from direct experience, and realising that it flowed due north for 400 miles from its source in Lake Bangweulu, and very likely hundreds more, the doctor had lost interest in Lake Tanganyika. The Lualaba, he told Stanley was ‘the central line of drainage [and] the most important line … [In comparison] the question

whether there is a connection between the Tanganyika and the Albert N’yanaza sinks into insignificance.’

12

But when Stanley reminded Livingstone that Sir Roderick Murchison and the RGS wanted the Rusizi to be settled, and offered to pay all the expenses of their journey to the northern tip of Lake Tanganyika, Livingstone agreed that they should go.

13

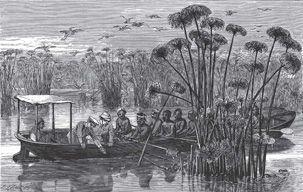

This was the very journey that had defeated Burton and Speke, but because Livingstone and Stanley refused to have anything to do with the local chief, Kannena, and instead accepted the loan of a large canoe from an Arab, Said bin Majid, and took with them only Stanley’s cook, his translator, two local guides and sixteen reliable Wangwana as rowers, they always kept control over their men. Speke’s and Burton’s people had refused to go on because of real or imagined dangers.

Stanley and Livingstone embarked on 16 November, six days after Stanley’s arrival at Ujiji.

14

Delighting in his self-acquired knowledge of Greek mythology, Stanley excitedly compared their ‘cranky canoe hollowed out of the noble

mvule

tree’ with Jason’s ship the

Argo.

They hugged the shore and Stanley was bewitched by ‘a wealth of boscage of beautiful trees, many of which were in bloom … exhaling an indescribably sweet fragrance’. The idyllic circumstances of the people also pleased him, with their fishing settlements, palm groves, cassava gardens and quiet bays.

15

Apart from an encounter with some stone-throwers, who Livingstone mollified by showing them the white skin of his arm and asking them whether they had ever been harmed by anyone of his colour, they experienced no hostility.

16

On reaching the head of the lake on 28 November, they found that the Rusizi flowed into Tanganyika rather than out of it. This was a major discovery and at a stroke ruled out Lake Tanganyika as being any kind of source or reservoir of the Nile. Yet even the discovery that the Rusizi flowed in would not force a retraction from Burton when he heard of it, since a river might conceivably flow out of the west side of the lake into the Lualaba and then continue northwards as the Nile. But realistically, it seemed that either the Victoria Nyanza or the Lualaba’s headwaters were now the only

serious candidates for being the Nile’s source. However, there

was

a serious problem with the Lualaba. The height Livingstone had calculated for Nyangwe had been 2,000 feet, which was the same as Baker’s height for his Lake Albert. Of course one or both of the measurements might be wrong. But if they were not, to get round these inconvenient heights (which ruled out a direct connection between the Lualaba and Lake Albert) Livingstone argued that the Lualaba could quite logically pass Lake Albert to the west and join ‘Petherick’s branch of the Nile’, the Bahr el-Ghazal.