Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure (34 page)

Read Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure Online

Authors: Tim Jeal

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Adventure, #History

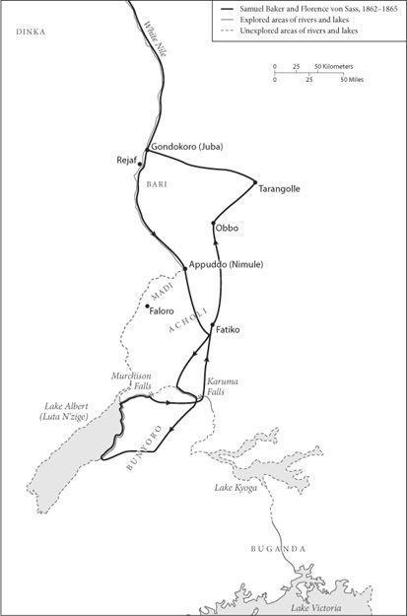

Journey of Samuel Baker and Florence von Sass.

As an analysis of the brutal life he was observing on the upper Nile, Baker understood such pessimism. But despite the dangers which he and Florence were facing, they were both natural optimists, believing that practical solutions could be found to problems, however intractable.

In Baker’s case his adaptability owed much to an unconventional youth and education. Although his father had been a banker, plantation owner and railway company director, Baker senior had not sent his sons to famous public schools, but had employed private tutors in England and Germany. So, despite his family’s wealth, Sam Baker would always feel an outsider in respectable upper-middle-class society. He had worked in his father’s London office, but only briefly. Finding it dull, he had begged to leave the City to run the family’s sugar estates in Mauritius. Married by the age of twenty-two, he had taken his new bride with him to the island, where she had given birth to, and lost, three children. The Bakers had then established a profitable agricultural settlement in the mountains of Ceylon, but because of ill-health had returned to England in 1855, along with four young daughters. The death of his wife in the same year had seemed only to increase Baker’s craving for adventure and danger, which his passion for big-game hunting could no longer satisfy. He had shot tigers in India, bears in the Balkans and elephants in Ceylon, and had brought to Africa a massive and ridiculously heavy elephant gun, ‘the baby’, which fired a whopping half-pound shell. Though of average height, Baker was broad-shouldered and powerfully built, and was not knocked over by the recoil of this gun, as most men were, even when propped up by another person.

12

Sam Baker described himself as ‘averse to beaten paths … not fitted for those harnessed positions which produce wealth; yet ever happy when unemployed, and too proud to serve’. He was

dogmatic and opinionated, and thought very little of Africans in general, but he respected and liked individual black people. He hated the slave trade, taught himself Arabic and spoke it tolerably well, and wrote entertaining books. Despite many bigoted opinions, he had done something which few British gentlemen would ever have contemplated: bought a woman in a slave auction.

13

Now, he and this remarkable person, in her loosely cut breeches and knee-length gaiters, were going to attempt a journey – which had defeated Miani, De Bono, and his agent Wad-el-Mek – becoming, if successful, the first Europeans to visit the unknown

nyanza.

Driven back from a point near the present Ugandan border by repeated attacks of fever, by mutinous porters, by African revenge attacks, and by cataracts, the slave traders’ failure was a warning to Baker and to Florence. Would

they

be able to rise to such a formidable challenge?

They started out with a distressing handicap. They loathed the slave trade – indeed Florence had been a slave – and yet they were going to be entirely dependent on Ibrahim and his slowly evolving plans. When he decided to make a series of raids in a particular area, instigated over several months, Baker and Florence were obliged to await his pleasure. Naturally they made the best of it – setting up ‘home’ together in a mud hut, keeping hens, growing lettuces, onions and yams in their garden, and trying their hand at making wine and

pombé.

Florence adopted a monkey as a pet, and later made Robinson Crusoe-like outfits for herself and her bearded lover. But whenever Ibrahim left on one of his brutal forays, Baker and Florence were compelled to come with him, lest in his absence, their own followers were overwhelmed by angry locals. ‘The traders convert every country into a wasps’ nest,’ lamented Baker, knowing that his men would probably be killed fetching water from the river, without Ibrahim’s followers being around to defend them. So Baker and Florence were obliged to accompany Ibrahim wherever his slave and ivory trading took him. ‘I am more like a donkey than an explorer,’ groaned the would-be discoverer of the Luta N’zige. In truth he was luckier than his real donkeys, which were already being

killed by the tsetse fly. So he was daily becoming more dependent on Ibrahim for porters; and there could be no knowing whether the Syrian would eventually agree to accompany him and Florence to Bunyoro. Being logical, why would any slave trader want to go to the country of a powerful king like Kamrasi, able to place ‘restrictions upon his felonious propensities’? At times Baker wondered whether he might do better to risk everything – including his life and Florence’s – on a dash for the lake with as many porters as he could manage to bribe. But for all his impetuosity and pride, Baker knew how to wait when it was absolutely necessary.

14

He and Florence endured nine months of moving about within the territory of the Latuka and Obbo peoples.

They were still 200 miles from their objective, and frequently in danger, despite Ibrahim’s presence (indeed partly because of it). Over again they heard the war drums ring out and were obliged to build barricades with their baggage. On one particularly menacing occasion, Florence laid out several hundred cartridges of buckshot, powder flasks and wadding on a mat, while Baker lined up his guns and rifles. Even little Saat strapped on his belt and cartouche-box and took his stand among the men, but at two in the morning, after many anxious hours of waiting, the dense crowds of armed men began to disperse. The Latuka had recently trapped a caravan of 300 Arabs, and after chasing them to the verge of a precipice, had thrust them over it with their spears. So the dangers were real enough. Meanwhile Baker’s own men continued to alarm him, and he was fortunate to end a near mutiny by knocking out the ringleader with a lucky punch.

15

Baker and Florence were in the village of the chief of the Obbo when they fell dangerously ill with malaria. Both had suffered bouts of fever before, but this time neither had the strength to help the other. They could not keep down water and were delirious. Katchiba, the old chief, was told that they were dying. On finding them lying helpless, he filled his mouth with water and squirted it about, including over the sick pair, and left confidently predicting that they would get better. Given how

many European traders had died in these latitudes, his optimism was surprising. But he turned out to be right. In the travellers’ hut, which was swarming with rats and white ants, Katchiba spotted Baker’s chamber pot and decided it would make a perfect serving bowl for important occasions. So he was deeply disappointed when told it was ‘a sacred vessel’ which had to accompany Baker everywhere he went.

16

With the Obbo that summer, Baker could not resist hunting elephant, although his horse was ‘utterly unfit [and] went perfectly mad at the report of a gun fired from his back’. When thrown to the ground twenty yards from a charging elephant, Baker seemed to be facing certain death, until the animal changed direction at the last moment and thundered after his departing horse. Without knowing it, Florence had narrowly missed the fate she dreaded most of all: being left alone in the heart of Africa.

17

Khursid re-joined his men in June, and though soon afterwards the slave trader ordered the slaughter of sixty-six local tribesmen, Baker still had no choice but to stay with him. Acts of casual brutality continued: a father who came to the camp to try to free his daughter, who had been enslaved, was gunned down and his body left for the vultures. Baker had already observed the order in which vultures fed on carrion: eating the eyes first, then the soft inner thigh and the skin beneath the arms, before consuming the tougher parts.

18

The Latukas’ eating habits also intrigued him. On one occasion, he saw the head of a wild boar (‘in a horrible state of decomposition’) being cooked over a fire, until ‘the skull became too hot for the inmates, [whereupon] crowds of maggots rushed pêle-mele from the ears and nostrils like people escaping from the doors of a theatre on fire’. Not that this stopped the cooks ‘eating the whole and sucking the bones’.

19

At first Baker welcomed the rains since they brought down the temperature to below 100 °F:

How delightful to be cool in the centre of Africa! I was charmingly wet – the water was running out of the heels of my shoes … the wind howled over the hitherto dry gullies … It was no longer the tropics; the climate was that of old England restored to me.

But soon all his stores were covered in mildew and even with constant fires burning it was impossible to dry out his possessions. By July the rains had made the rivers too high for anyone to travel south, as he discovered during a week’s reconnaissance. Only when the dry season started in October would travel become possible again. By then, he and Florence had suffered many more attacks of fever and their stock of quinine had been reduced to a few grains. Their horses and donkeys were all dead and they were too weak to walk, so there was still no hope of an early departure. Even when Baker invested in three oxen, ‘Beef’, ‘Steak’ and ‘Suet’, he and Florence found they lacked the strength to mount them. But at least he managed to persuade Ibrahim to come with him to Bunyoro as soon as he and Florence were able to make a start. In part this had been achieved by repetition of his promise to obtain for Khursid and Ibrahim favourable terms for acquiring ivory from Kamrasi; and in addition, Baker offered him a good supply of beads from his substantial store, with which to make his purchases. Ibrahim had few beads of his own and was already indebted to Baker for 65 lb.

20

On 4 January 1864, Florence and Baker swallowed the last grains of quinine in their medicine chest, and prepared to head south the following day. After an hour or so of travelling, Baker’s ox bolted, obliging him to walk eighteen miles on the first day, and Florence’s beast was stung by a fly and plunged so suddenly that she was thrown to the ground and badly shaken up. The next day Ibrahim sold two well-behaved oxen to the exhausted Baker and his bruised mistress, who reached the Asua river, close to modern Nimule, after only four days’ riding.

On their way there, on entering villages Ibrahim’s men had ransacked granaries for corn, dug up yams and ‘helped themselves to everything as though quite at home’. Baker made no mention in his diary of feeling any qualms about urging the agent of a notorious slave trader to enter a kingdom where the trade was not yet endemic. His hero, Speke, had not accepted help from slave traders until he had left the kingdoms of Buganda and Bunyoro and was moving towards an area already devastated

by slavers. It was true that Ibrahim had promised Baker that he would not enslave people or steal cattle while in Bunyoro; but his word would mean very little in future.

21

When Baker was twelve miles south of Faloro in the land of the Madi, he could see with his own eyes that many villages had been burned to the ground and the whole country laid waste by Mohammed Wad-el-Mek, the

wakil

of Andrea De Bono. He even noted that: ‘It was the intention of Ibrahim … to establish himself at Shooa [south-east of Faloro] which would form an excellent

point d’appui

for operations to the unknown south.’ So Baker clearly realised that his current journey would encourage Khursid Agha (Ibrahim’s master) to compete with De Bono for control of the slave and ivory trade in ‘the unknown south’.

22

Perhaps it eased Baker’s conscience to think that Khursid would have pressed on into Bunyoro anyway. It was a token of the intensity of Baker’s desire to achieve fame as an explorer that he was prepared to ignore his conscience so completely. In Khartoum, two years earlier, he had written angrily to

The Times

(25 November 1862) about the terrible evils of ‘man-hunting’ and the unimaginable suffering it caused.

While Baker was at Shooa, which was about eighty miles from Kamrasi’s capital, a boy who had formerly worked for Mohammed Wad-el-Mek was brought to the explorer. This youth told him that soon after his master had escorted Speke and Grant to Gondokoro from Faloro, he had marched south into Bunyoro, along Speke’s route at the head of a large force. De Bono, Wad-el-Mek’s master, had ordered him to support Rionga in his longstanding struggle to supplant his brother, Kamrasi, as ruler. Success would provide De Bono with a compliant monarch to do business with – or so he had hoped. Kamrasi, however, had fought back and survived, although 300 of his subjects had been killed in the fighting. It struck Baker forcibly that Kamrasi would now assume, quite wrongly, that it was no coincidence that he had been attacked by the very people who had escorted Speke to Gondokoro. Inevitably the ruler of Bunyoro would suppose that Wad-el-Mek had been sent by Speke to attack him.

At Gondokoro, Speke had himself warned Baker on no account to set foot in the territory which Rionga controlled, or Kamrasi would think of him as his greatest enemy’s ally and would stop him travelling to the lake.