Exiles in Time (The After Cilmeri Series) (37 page)

Read Exiles in Time (The After Cilmeri Series) Online

Authors: Sarah Woodbury

Tags: #medieval, #prince of wales, #middle ages, #historical, #wales, #time travel fantasy, #time travel, #time travel romance, #historical romance, #after cilmeri

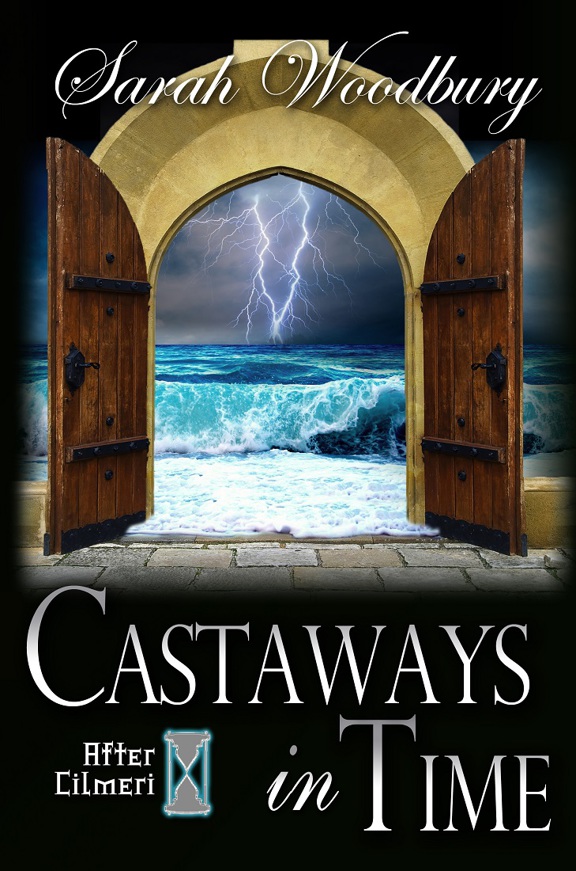

Castaways in

Time

With a scarlet fever epidemic raging

throughout London, a rogue baron on the loose, a new baby keeping

him up at night, and a kingdom to run, the last thing David has

time for is a trip to the twenty-first century. But as he should

know by now, time waits for no man, not even the King of England

…

Release date: September 24,

2013

Look for

Castaways in Time

wherever ebooks are

sold.

Thank you so much for

continuing with the

After Cilmeri

series. It’s readers like you who make my job the

best in the world! If you haven’t already, and would like to know

when I have a new release, you can enter your name into the side

bar on my web page:

http://www.sarahwoodbury.com/

Meanwhile, keep reading for

the first chapter of

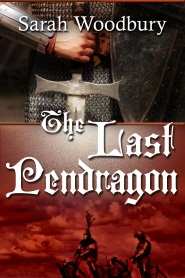

The Last

Pendragon

, the first book of another series

set in Dark Age Wales:

Sample:

The Last Pendragon

What if the myths and

legends were once real? What if gods and demons really walked among

us?

He is a king, a warrior, the last hope

of his people—and the chosen one of the sidhe.

Set in 7th century

Wales,

The Last Pendragon

is the story of Arthur's heir, Cadwaladr ap

Cadwallon (Cade), and his love, Rhiann, the daughter of the man who

killed Cade's father and usurped his throne.

Born to rule, yet without a kingdom,

Cade must grasp the reins of his own destiny to become both

Christian king and pagan hero. And Rhiann must decide how much she

is willing to risk to follow her heart.

The Last Pendragon

is a 98,000 word (430 page) tale of the

supernatural set in Dark Age Wales.

Chapter One

Aberffraw, North Wales, Kingdom of

Gwynedd

655 AD

Rhiann

T

he smell of smoke and sweat filled the hall, mingling with the

overlay of roast pig and boiled vegetables. More soldiers than

usual sat at the long tables, here to celebrate their victory. The

mood was subdued, however, not the wild jubilation that sometimes

accompanied triumph and caused Rhiann’s father to lock her in her

room in case he couldn’t control the men.

Today, the drinking had begun in

earnest the moment the men had returned from the fight and settled

into a steady rhythm Rhiann had never quite seen before. Here and

there, a hand clenched a cross hung around the neck or an amulet

against the powers of darkness, that should her father see, might

mean death for that soldier. For a man to ask the gods for

protection instead of the Christ meant he was less afraid of the

King of Gwynedd than someone, or perhaps something, else. Rhiann

had been afraid of her father her whole life and couldn’t imagine

fearing another more, not even the demons that were said to walk

the night, hungering for men’s souls.

Perspiration trickled down the back of

Rhiann’s dress, made of the finest blue wool that her father had

gotten in trade from merchants on the continent. The country folk

jested that sheep outnumbered men in their lands. Like the

shepherds who traveled through the mountains with them, they were

also tougher here than those in warmer, dryer climates and their

wool not as soft. The Saxon threat was enough to keep the Cymry

within their own borders, but the sailors still took to the western

seas, bringing in trade goods of wine, finely wrought cloth,

metalwork, and pottery.

For once, Rhiann’s father, King

Cadfael of Gwynedd, had eaten little and drunk less. For her own

preservation, Rhiann had always been sensitive to his moods and

noted the exact instant his disposition changed. He shifted in his

seat and rolled his shoulders, like a man preparing for a battle

instead of the next course of his meal. A moment later, the big,

double doors to the hall creaked open, pushed inward by two of the

men who always guarded them. The rain puddled in the courtyard

behind them and Rhiann wished she were out in it instead of here;

anywhere but here.

She kept her place, standing behind

and to the left of her father’s chair. It was her duty to tend to

his needs at dinner as punishment for her refusal to marry the man

he’d chosen for her. Rhiann hadn’t turned the man down because he

didn’t love her, or she him; she knew better than to wish for that.

It was a hope for mutual respect for which she was holding out. But

even this seemed too much to ask for an unloved, bastard daughter.

Consequently, Rhiann spent her days as a maidservant, albeit one

who worked above stairs. She didn’t regret her station. As the

months had passed, she’d come to prefer it to sharing space at the

table with her father and his increasingly belligerent

allies.

Silence descended on the hall as two

of King Cadfael’s men-at-arms entered, dragging between them a

young man whose head fell so far forward that no one could see his

face. He was visibly collapsed, with his arms dangling over the

guard’s shoulders and his feet trailing behind him. As the trio

progressed along the aisle between the tables toward the King’s

seat, the youth seemed to recover somewhat, getting his feet under

him and managing to keep up with their strides. As he came more to

himself, he straightened further.

By the time he reached the

dais on which Rhiann’s father sat, he was using the men-at-arms as

crutches on either side of him. Because he was significantly taller

than they, it was even as if he was hammering them into the ground

with his weight. His footsteps rang out more firmly with every

stride, echoing from floor to ceiling, matching the drumming of

Rhiann’s heart. The closer he got to her father, the harder it

became to swallow her tears.

By the souls

of all the Saints, Cadwaladr, why did you come?

Rhiann had been her father’s prisoner

her whole life, unable to escape his iron hand. The high, wooden

palisade that circled Aberffraw had always signified prison walls

to her, rather than a means to protect her from the darkness

beyond. This young man had grown up on the other side of that wall.

He’d not had to enter here. He’d had a choice, but had recklessly

thrown that choice away and was now captive, just as she was. She

felt herself dying a little inside with every step he took as he

approached Cadfael.

The young man, Cadwaladr, the last of

the Pendragons, fixed his eyes on those of the woman sitting beside

the King. She was Alcfrith, Cadfael’s wife, taken as bride after

the death of Cadwaladr’s father. Rhiann couldn’t see her face, but

from the back, the tension was a rod up her spine and her shoulders

were frozen as if in ice.

“

Hello, Mother.”

Cadwaladr’s lips were cracked and bleeding, puffy from the beating

that had bruised the whole length of him. Rhiann had heard they’d

as close to killed him as it didn’t matter, but from the look of

him now, the men-at-arms to whom she’d spoken had

exaggerated.

“

Son.” Alcfrith’s voice as

stiff as her body.

Rhiann’s father ranged back in his

chair, legs crossed at the ankles to project his calm and deny the

importance of the moment. “Foolish whelp. I’d thought you’d put up

more of a fight, not that I regret the ease of your defeat. This

will allow me to reinforce my eastern border more quickly than I’d

thought. Penda will be pleased.”

“

You and I both know why my

company was not prepared for battle today,” Cadwaladr

said.

Cadfael shrugged. “Your men are dead

and you a shell of a man. What did you think? That the people would

welcome you? That I would let you take my lands?”

“

My lands,” Cadwaladr

said.

Rhiann’s father sneered his contempt.

He reached out an arm to Alcfrith and massaged the back of her

neck. She didn’t bend to him. If anything, the tension in her

increased. “You meet your death tomorrow, as proof of your

ignobility.”

Cadfael waved his hand to Rhiann,

signaling her to refill his cup of wine and that the interview was

over. She obeyed, of course, stepping forward with her carafe. The

guards tugged on Cadwaladr, but as he moved, Rhiann glanced up and

met his eyes. It was only for a heartbeat, but in that space it

seemed to Rhiann that they were the only ones in the room. She

expected to see desperation and fear in him, or at the very least,

pain. Instead, she saw understanding. She could hardly credit it.

When had she ever known that?

“

You’re wrong, Father,”

Rhiann said, as the guards hauled Cadwaladr away. “Cadwaladr comes

to us as a defeated prisoner, and yet, he has more honor, more

nobility, than any other man in this room.”

“

He is the Pendragon,”

Alcfrith said, with more starch in her voice than Rhiann had heard

in many years. “Cadfael can’t change that, even by killing

him.”

Rhiann’s father snorted a laugh into

his cup before draining it. He didn’t even slap the women down, so

sure was he of his own omnipotence. “You may keep your dreams.” He

pushed himself to his feet and turned to leave. “The dragon is

chained; the prophecy dead.”

Rhiann had heard about Cadwaladr her

whole life. As a child, men in Cadfael’s court had spoken of him as

if he were a demon from the Underworld, or worse, a Saxon, coming

to steal their home like a thief in the night. Later on, as she

began to piece the story together, she realized that he was only a

little older than she was, twenty-two now to her twenty, and their

words said more about their own fears than Cadwaladr’s

power.

Rhiann’s father had married

Cadwaladr’s mother after Cadwallon’s death in battle, many miles

from Aberffraw. The High Council of Wales had wanted peace in

Gwynedd, in order to focus the concerted attention of all the

native British rulers on the threat of the encroaching Saxons.

Throughout Rhiann’s life, the Saxon kingdoms had been growing in

number and power. Two centuries before, the British kings had

invited them in, but once here, could no longer control them. The

Saxons had overrun nearly all of what had been British lands only a

few generations before.

By now, everyone knew that the Saxons

wouldn’t be returning to their ancestral lands across the water any

time soon. Her father, Cadfael, and Cadwallon before him, had

allied with Penda of Mercia, but it had left a sour taste in the

collective mouth of their people. All the Cymry knew that it was

only a matter of time before the Saxons turned their gaze

covetously on Wales.

The Council had settled upon Cadfael

as the man to impose peace amid the chaos of constant war, provided

Alcfrith agreed to the marriage. Rhiann suspected that ‘agreed’ was

too positive a word, and like most noble women, Alcfrith had had

little choice in the matter. While the High Kingship had never

materialized, and he didn’t even rule all Gwynedd like Cadwallon

had, Cadfael did control a significant piece of it: Cadwaladr’s

birthright, as he’d said.

What Alcfrith had not done upon her

marriage was give up her son, instead sending him away to be raised

by another. Rhiann’s father had raged at Alcfrith time and again,

demanding to know to whom she’d given him. Alcfrith had refused to

say, and perhaps that was the bargain she’d made—safety for her

son, in exchange for her allegiance.