Executed at Dawn (5 page)

Authors: David Johnson

Military Police

Military Police will be employed to prevent traffic from passing by the place of execution for half an hour before the hour fixed for execution and until all traces of its having taken place have been removed.

Firing Party

To consist of an Officer, 1 Sergeant and 10 men of the prisoner's unit. The sergeant will not fire. The Officer will be present at the promulgation of the sentence to the prisoner and will on that occasion receive from the APM any instructions as necessary. He will previously instruct the firing party as to their duties, impressing on them that the most merciful action to the prisoner is to shoot straight.

Procedure

The APM is responsible for all arrangements and for seeing the sentence carried out.

After promulgation, the prisoner should be allowed anything he wishes to eat, drink or smoke within reason. He will also be provided with writing materials if desired.

When being prepared for execution the prisoner will be identified by the NCO in charge of the guard in the presence of the APM and Medical Officer. The APM will collect pay book and identification disc and make them over to the NCO in charge of the guard for delivery at the unit's Orderly Room.

The prisoner will be handcuffed or have his wrists bound before being taken to the place of execution.

The Medical Officer will provide a three cornered bandage for blindfolding and a small paper disc for fixing over the heart. He will adjust these when requested by the APM.

He will also arrange for a stretcher in case the prisoner is unable to walk.

Firing party

Rifles will be loaded by the Officer i/c Firing Party and will be placed on the ground. One rifle will be loaded with a blank. Safety catches will be placed at safety. Distance from post 5 paces. The Officer will bring with him a loaded revolver.

The firing party will be marched into position by the APM whilst the prisoner is being tied to the post. The APM will so time this that the firing party will be ready for action simultaneously with the completion of the tying up.

The firing party will march in two ranks, halt on the rifles, turn to the right or left, pick up the rifles and come to a ready position, front rank kneeling, rear rank standing. They will press forward safety catch and come to the âpresent' on a signal from the APM. The Officer, when he sees all the men are steady, will give the word âfire'. This is to be the only word of command given after the prisoner leaves the place of confinement.

When the firing party has fired, it will be turned about and marched away at once by the Sergeant, the Officer remaining behind.

The Medical Officer will go forward and examine the body. If he considers that life is not extinct he will summon the Officer i/c of the firing party, who will complete the sentence with his revolver.

The Medical Officer will certify death and sign the death certificate which he will hand to the APM.

Removal of body

When death has been certified, the body will be unbound and removed to the grave under arrangements previously made by the unit.

The notes make it clear that from the time a death sentence has been passed on a man, he would be handed into the custody of the APM of the division, who would be in charge of making all the necessary arrangements and liaising with the prisoner's commanding officer, as necessary, once he was in receipt of all the formal paperwork from divisional headquarters.

The origins of these notes remain a stubborn mystery. The earliest documentation that the Royal Military Police Museum has concerning military executions is the

Provost Training in Peace and War, being the Manual of the Corps of Royal Military Police 1950

(pp. 213â15), which sets out a procedure that very closely accords to those issued to Guilford in 1917 â which is interesting in itself, as the death penalty was virtually abolished in the military in 1930, as will be discussed later.

The overall impression left by the notes given to Guilford is that they are very detailed and read as if based on the accumulation of good practice to date, although the source of the good practice and whether it applied across the whole British Army has not been possible to determine at the time of writing.

It is not clear why these notes were given to the chaplain and not to the APM, who had responsibility for the conduct of the execution. The likeliest explanation, particularly as Guilford was handed a carbon copy, is that the notes were given to him by the senior chaplain as a copy for his information about what was to happen so that he was forewarned and prepared â the equivalent of copying someone in on an email, for example.

In addition, although some of its phraseology might appear to be unmilitary in terms of its structure and language, Peter Fiennes has confirmed that although torn and a little ragged, it was in all other respects intact.

Instructions do exist for the execution of Private John Skone, of the 2nd Welch Regiment, on 10 May 1918, who was found guilty of the murder of Lance-Sergeant Edwin Williams on 13 April 1918. These were sent by Major Joseph Wesley, the deputy assistant adjutant-general, to Brigadier-General Morant, and are much briefer although essentially covering the same points as those issued to Guilford (Putkowski and Dunning, 2012). There is also a tantalising report of the experiences of Lieutenant-Colonel H. Meyler (Moore, 1999) which indicates that such regulations may have existed. Meyler recalled an execution in 1915 where he had detailed a firing squad from âA' Company to shoot a man from âB' Company, and went on to say, âYou may say that regulations do not allow this to be done. I have seen it done myself.'

Therefore, despite the concerns raised in the previous paragraph and in the absence of alternative documentation, the Guilford notes will be used as the basis for examining the roles and experiences of those who played a part in the executions.

Soldiers who had been executed were later buried in the same cemeteries as their comrades who had died in action. In September 1916, the adjutant-general issued an order which read:

There is no rule that any man who has suffered the extreme penalty of the law should be buried near the place of execution. Any man who suffers the extreme penalty of the law may be buried in a cemetery, the inscription being marked DIED instead of KILLED IN ACTION or DIED OF WOUNDS.

â â â

Having taken into account the standards of the time, there are two major areas of concern: namely, the lack of a right to an appeal and the part played by chance. The right to an appeal is enshrined in British civilian law, so why did the politicians, presumably under pressure from the British Army hierarchy, agree to the removal of this right under military law? The simplest explanation is likely to be that it was because the offences were committed whilst on active service, and the army wanted to avoid having resources tied up in dealing with what could potentially be large numbers of appeals. This seems to fall under the term âexigencies of the service', which seems to give approval for doing less than would normally be acceptable as circumstances demanded.

It seems an unavoidable conclusion that chance played too big a part in whether a death sentence was confirmed and carried out, and yet that did not seem to trouble the military hierarchy or the politicians of the day. If a soldier subject to military law was found guilty of an offence committed on active service that was subject to a mandatory death sentence, then in the absence of any mitigation, that should have been the sentence. It should not be used as a tool to correct perceived deficiencies in the discipline and fighting abilities of a battalion or regiment as this introduces a worrying level of subjectivity into the proceedings â as seems to be the case with Sir Douglas Haig's decision-making criteria, based on the limited number of diary entries that he made, which were both troublingly subjective and opaque. If Sir Douglas Haig, for example, considered that someone needed to be made an example of because âThe state of discipline in this battalion is not very satisfactoryâ¦', then, in his mind, a condemned soldier was expendable in the cause of making that example.

In the case of Private Arthur Earp, of the 1/5th Royal Warwickshire Regiment, who was executed on 22 July 1916 for the offence of quitting his post, Haig's attitude to capital punishment and the expendability of an individual soldier was made clear. It had been recognised by the court martial and those in the chain of command that Private Earp had been âunnerved by a barrage' and so, at each level, a recommendation for clemency had been supported â with the exception of General Gough, his army commander, and Haig as the commander-in-chief. Haig's practice was simply to write âconfirmed' together with his signature on the paperwork of those sentenced to death. However, in Private Earp's case, he wrote, âHow can we ever win if this plea is allowed?'

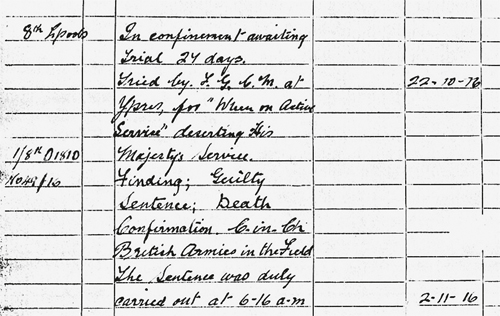

Private Bernard McGeehan was shot for desertion at 6.16 a.m. on 2 November 1916. He was almost certainly autistic: âEver since I have joined up the men have made fun of me ⦠Every time I go into the trenches they throw stones at me and say it is shrapnel and they call me all sorts of names. I have been out here 18 months and have had no leave.'

Almost certainly, Private Earp was suffering from shell shock and Haig was clearly concerned that any clemency shown would legitimise the condition and open the gates to a flood of similar cases as men sought to escape the trenches (Sheffield, 2012). It is clear, therefore, that Earp was shot purely and simply because he had shell shock and to discourage others from using it as an excuse for avoiding what Haig saw as their duty.

Such attitudes pre-dated Haig: in 1915, General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien, commander of the Second Army, wrote to the officers of the court martial convened to consider the case of Fusilier Joseph Byers, 1st Royal Scots Fusiliers: â⦠would urge that discipline in the 1st Battalion Royal Scots Fusiliers had been bad for some time past, and that a severe example is very much wanted.'

General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien. âThere is a serious prevalence of desertion to avoid duty in the trenches, especially in the 8th Brigade and I am sure the only way to stop it is to carry out some death sentences.'

The impression that life was cheap and of no value beyond the needs of the army is one that, 100 years later, gives pause for thought, but in 1914â18 it would not have seemed so surprising. This is also a point that other military historians dispute, arguing that the officers and their men developed strong bonds, but, while this might have been the case at battalion level, those bonds would have been weaker the further up the command chain that decisions were being made, when the individuality of the person was replaced by a collective view.

This raises a further interesting point because, if a battalion was underperforming and this had been in some way drawn to the commander-in-chief's attention, then the battalion as a whole bore a collective responsibility if the sentence was confirmed. There is no evidence to suggest that this was ever acknowledged, but we will discuss later the impact that death sentences had within battalions and regiments.

The Irish Government Report (2004) gave other examples of the part played by chance and the collective responsibility of a condemned man's comrades:

There have been far too many cases already of desertion in this Battalion. An example is needed as there are many men in the Battalion who never wished to be soldiers.

I consider that, in the interests of discipline, the sentence as awarded should be carried out.

[I recommend] the extreme example be carried out as a deterrent to other men committing a similar offence.

The state of discipline of the unit as a whole is good, but there are individuals (such as the accused) in the unit who take advantage of leniency and for whom an example is needed.

Under ordinary circumstances I would have hesitated to recommend the capital sentence awarded be put into effect as a plea of guilty has been erroneously accepted by the court, but the condition of discipline in the Battalion is such as to render an exemplary punishment highly desirable and I therefore hope that the Commander in Chief will see fit to approve the sentence of death in this instance.