Executed at Dawn (17 page)

Authors: David Johnson

As the Conservative government could not be stirred into action, Mackinlay moved a Private Members Bill in 1993, which sought to âprovide for the granting of pardons to soldiers of the British Empire forces executed during the Great War of 1914 to 1919'. Mackinlay's bill, however, did not include provision for pardoning those executed for murder or mutiny but sought to have a tribunal consisting of three judges set up to review, report and make a recommendation as to a pardon on the remaining cases. The content of the bill would have been welcomed to varying degrees by both sides of the debate, but it went further by seeking to provide for compensation to be paid at the discretion of the Secretary of State on a case-by-case basis.

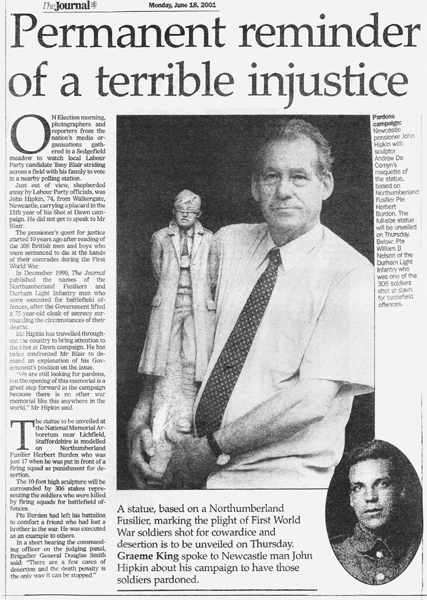

John Hipkin in June 2001, shortly before the unveiling of the statue of Northumberland Fusilier Herbert Burden, who was shot at the age of 17. The statue is at the National Memorial Arboretum (see image opposite). John Hipkin holds a model of the 10ft-high sculpture.

A Private Members Bill is never likely to be passed unless it is supported by the government, and this one was to be no different, as was the case with an Early Day Motion (No.53) tabled on 23 November 1993, which asked:

That this House calls upon the Government to issue pardons to those men executed by firing squad during the First World War, many murdered at the orders of their own officers, without proper trial or defence, despite being shell shocked or otherwise mentally ill, thereby removing the unfair shame and stigma suffered by their families even to this day.

This Early Day Motion attracted eighty-one signatures, mainly from Labour MPs, and was followed by another Early Day Motion on 30 November 1994 (No.154), which asked:

That this House calls upon the Prime Minister to posthumously pardon those United Kingdom citizens executed in the First World War on orders of officers who often failed to observe the Army Act; and notes that some citizens were obscenely executed in abattoirs to the permanent disgrace of this country and its officer corps.

It attracted forty-five signatures, mainly from Labour MPs again, with no support once more from the Conservatives.

On 13 December 1995, Andrew Mackinlay rose to his feet in the House of Commons to raise once more the issue of pardons for those who had been executed in the First World War, on the grounds that:

The men were not given the opportunity to prepare an adequate defence. Many of them were not represented at all; if they were represented, it was by somebody who was demonstrably not qualified to do so. After their field court martial were completed, they were often not told what their sentence was until between 12 to 24 hours before it was carried out. Not only is that demonstrably unfair and unjust, but for all the 300-plus soldiers, there was no right of appeal against the sentence of death.

In what turned out to be another futile attempt to change the Conservative government's mind, he added:

My postbag shows beyond all doubt that, in a sense, those men have been pardoned by the highest court in the land â British public opinion. If one discusses the matter with people in our streets and in clubs among ex-service men and women who went through the first and second world wars, and with serving service men and women today, one finds that, overwhelmingly, they proclaim that those men were brave British soldiers who should be granted pardons. I hope for and look forward to the support not only of Opposition Members but of the many Conservative Members who have over the months told me of their support for such pardons to be granted.

In 1995, the office of Tony Blair, the leader of the opposition, perhaps with a willingness at that stage still to embrace populist views, issued a statement giving an undertaking that a future Labour government would look sympathetically at this matter. It seems clear, judging by what later transpired, that the statement was made before any documentation had been looked at or legal advice sought.

In a debate in the House of Commons on 9 May 1996, the Conservative government's position was outlined as follows:

The rules that applied during the first world war differ from those now governing the conduct of courts martial. However, these soldiers were convicted by a properly constituted court, according to the laws and procedures of the land, of an offence punishable by the imposition of the death penalty. That we do things differently today cannot alter the fact, uncomfortable as it might be for many of us.

Andrew Mackinlay replied:

The principles of English law, that people should have a fair trial, be able to prepare a defence and be able to appeal against sentence, were not invented after 1918. They are the basic principles of English law since long before, and were denied to those men in our century.

An amendment to the Armed Forces Bill, which would have secured pardons for those executed in the First World War, was defeated by 203 votes to 129. Among the Labour opposition who voted in support of the amendment were Dr John Reid, Douglas Henderson and John Spellar, and all three went on to become armed forces ministers after 1997.

Understandably therefore, the Shot at Dawn campaign had high expectations of the Labour government that was elected in 1997, and initially were not disappointed when a review was carried out, and an announcement stated:

For some of our soldiers and their families, however, there has been neither glory nor remembrance. Just over 300 of them died at the hands not of the enemy, but of firing squads from their own side. They were shot at dawn, stigmatised and condemned â a few as cowards, most as deserters. The nature of those deaths and the circumstances surrounding them have long been a matter of contention. Therefore, last May, I said that we would look again at their cases. The review has been a long and complicated process. (Official Report 24 July 1998; Vol. 316, c. 1372.)

But disappointment followed as Dr John Reid, the armed forces minister, announced in July 1998 (see Appendix 1) that he could not agree to the granting of any blanket pardons, something which the Shot at Dawn campaign had in fact never asked for, as claimed by those who opposed its objective. It had become apparent to Dr Reid from the courts martial papers that he had read â and he claimed to have read over half of those available â that many of those concerned had in fact been guilty based on the standards and practices that existed at the time of the First World War. Dr Reid explained in 2009: âI was told on the highest legal advice at the time â I can say that now that I am not a Minister â that I could not give a legal pardon' (Hansard).

Dr Reid had also consulted widely in arriving at his decision, including having a meeting with Judge Anthony Babington and Julian Putkowski (Hansard, 20 March 1998). One problem that Dr Reid and his advisers encountered was the variation in the courts martial papers available to them, as some were quite comprehensive while others consisted of just one sheet of paper, and they were handwritten.

In making his announcement, he expressed his regret for all those killed in the First World War, whether by the enemy or by execution. His decision was based on concerns that the passage of time caused the grounds for a blanket pardon, on the basis of their unsafe conviction, to be non-existent because no new evidence could be presented and no new witnesses could be forthcoming. He concluded that, as a result, any review would leave a significant number of the men re-condemned again because any judgement made had to be based on evidence rather than belief. There is no doubt that, had he felt able to agree to the granting of pardons, he would have done so â as evidenced by his interest in the matter, the support he gave in the House of Commons in 2006, and the explanation that he gave in 2009.

Therefore, in 1998, the Labour government, which in opposition had appeared to support the campaign, decided that it could not issue a blanket pardon because it was unable to âdistinguish between those who deliberately let down their country and their comrades and those who were not guilty of desertion or cowardice'. Keith Simpson, MP, was a newly appointed junior front bench defence spokesman when he had to respond to Dr Reid's statement, but in a debate on 18 January 2006 he shed some light on to the position in the 1970s when he said:

It is interesting that, in the 1970s, a large number of Labour Members then in opposition felt very strongly that the then Conservative Government and previous Labour Governments had been far too secretive about the records relating to the men executed and that the likelihood was that there had been a cover-up.

If the Ministry of Defence had hoped that Dr Reid's statement would be the end of the matter, it was to be disappointed because, dismayed but not deterred, the Shot at Dawn campaign kept pressing its case and Andrew MacKinlay said, âI am deeply disappointed that the Government still refuses to grant pardons but these people have already been pardoned by the highest court in the land, British public opinion' (

Daily Telegraph

, 22 June 2001).

Opponents of the campaign continued to argue about the futility of changing history and that a focus on those executed did a disservice to those killed and wounded in the First World War. But Dr Reid was given cause to reconsider this decision as he explained in 2009 (Hansard):

During the interval between being Armed Forces Minister and being Secretary of State, I discovered that New Zealand had apparently managed to accomplish that which I had been told was impossible in Britain. Naturally, and in my normal delicate fashion, I interviewed some of my officials who were still there about why that which we had found impossible had been found possible elsewhere. We re-opened the inquiry, and I am glad to say that my successor, my right hon. Friend the Member for Kilmarnock and Loudoun [Des Browne], did a great deal of work on the matter as Defence Secretary. The result is as is known.

The Shot at Dawn campaign was not daunted and continued to argue for pardons, with a particular focus on the cases of the underage soldiers. It is a further disturbing thought that, in the same way that some of those executed were below the age of 19, having joined up when they were below the minimum age, it is also likely that some of those in the firing squads would have been under the age of 16 as well.

On 16 September 1915, Brigadier-General F.G. Anley, who commanded the 4th Division, issued routine orders that showed that the army was already aware of the problem of underage soldiers and its attitude to the problem. The orders state: âLads who are under 17 years of age, according to their birth certificate, which should be produced, will be sent to England unless they are passed fit for service and wish to remain at the front.' This statement is interesting because it made it a condition of repatriation that the âlad', who was already at the front, had to produce a birth certificate â how many were likely to have this document with them in a legible state after service in a trench? The production of a birth certificate was not something the army had required as a condition of enlistment.

The Ministry of Defence's head of Army Historical Branch, Miss A.J. Ward, OBE, made the ministry's position clear on the execution of underage soldiers in a letter dated 24 March 1999 to John Hipkin:

You also mention that a number of soldiers who were under age were illegally tried and executed. I am afraid this is not the case. Anyone over the age of 14 was deemed legally responsible for his actions, and Army regulations provided no immunity from Military Law for an underage soldier. While measures were taken to remove under age soldiers from the front line when their ages were discovered, anyone who had voluntarily placed himself â albeit through fraudulent enlistment â under Military Law, could not exempt himself from the legal consequences of doing so. John Reid (Secretary of State) paid particular attention in his review to the views, and representations which you, the veterans, and especially the families of those executed made to him. He also consulted and took advice from a number of people outside the Ministry of Defence on historical, legal, and medical aspects of the matter.

In effect, the Ministry of Defence's position was that underage soldiers who had given a false age when enlisting had willingly placed themselves under military law, which stipulated the age of criminal responsibility as 14. This meant that desertion by any serviceman, including those who were technically underage, was correctly punishable by death if so directed by a court martial. The letter also sought to clarify the reasons for the embargo of the courts martial records: namely to âsafeguard the privacy of individual servicemen and their families',

which

has been discussed elsewhere in this book.