Ex Libris: Confessions of a Common Reader (15 page)

Read Ex Libris: Confessions of a Common Reader Online

Authors: Anne Fadiman

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #Literary Criticism, #Essays, #Books & Reading, #Literary Collections, #Books and Reading, #Fadiman; Anne

My parents were merely passing on the legacy they had received from their own parents. When my mother moved from Utah to California at age nine, her father covered a sixteen-foot-long wall with bookcases, and her mother sheathed each shelf with nubbly beige wallpaper. My mother spent that summer reading the complete works of Dickens. My father grew up in Brooklyn in an immigrant family too poor to take him to a restaurant until he reached his teens, but not too poor to fill two black-walnut bookcases with the likes of Scott, Tolstoy, and Maupassant. “I read Ibsen when I was eight,” he told me. “Even before that, Ibsen was

there

. I knew he was a great Norwegian dramatist, part of a world I was somehow moving toward.” Last week he startled me by reciting, in an Irish accent, several lines spoken by Private Mulvaney in Kipling’s

Soldiers Three

, which he had read (in a red edition with the title stamped in gold) eighty-five years earlier.

When I was fourteen, I noticed that the Late Augustan shelves in my father’s British section contained a book that was turned spine in. Naturally, I made a beeline for it. It was

Fanny Hill

. (The effort to shield my innocent eyes was so obviously destined to backfire that a couple of years later, when I borrowed Freud’s

Psychopathology of Everyday Life

from the Austrian shelf, I concluded my father had unconsciously

wanted

me to find

Fanny Hill

.) It is my opinion that parental bookcases are an excellent place for teenagers and erotica to meet for the first time, especially if the works are of high literary quality (John Cleland, Frank Harris, and Anaï’s Nin, let us say, rather than Xaviera Hollander). Not only are the books easy to access, but the teenagers learn that, incredible as it may seem, their parents have sexual feelings too.

Fanny Hill

looked well thumbed.

When I asked several writers I know what books they remembered from their own parents’ shelves, a high proportion were lubricious. Campbell Geeslin, a novelist and editor who grew up on a West Texas ranch, spent many hours in the embrace of

A Treasury of Art Masterpieces

, particularly the color reproduction of Manet’s

Olympia

, whom he describes as “wearing nothing but a black ribbon around her throat, with her legs slightly crossed to hide the part I most wanted to see.” The scholar and poet Charles Bell, whose father owned the second largest library in Mississippi, pored over the more risqué passages in Richard Burton’s sixteen-volume translation of

The Thousand and One Nights

. When he inherited the set half a century ago, he discovered an oh-so-faintly penciled list of numbers on the back flyleaf of volume 4: page references to his dead father’s own favorite salacities.

Those sixteen volumes now grace Charles Bell’s library, one of the largest in Santa Fe. Campbell Geeslin did not inherit

A Treasury of Art Masterpieces

, only the fruitwood coffee table upon which it once reposed. He did, however, inherit the family Bible. Sixty years ago, his father read a chapter from it every night, leading Campbell to believe that Saul and David spoke with West Texas accents. During the readings, his mother sat at her dressing table, applying Pond’s cold cream. “Whenever I open the Bible today,” says Campbell, “I hear my father’s voice and I smell my mother’s face.”

Some of my friends do not intend to leave their books to their children, believing that they would be a burden: a never-ending homework assignment, boxed and unboxed with every move, that would reproach the legatees from on high. I do not agree. I intend to leave my library to my children. My daughter already likes to look at our books and imagine what they might be about. (

Rabbit at Rest

is “the story of a sleepy bunny”;

One Man’s Meat

is “a mystery about some men at a dinner table, and one of them gets steak but the others only get broccoli.”) Someday she will read them, as I read

In Praise of Folly

, whose Holbein frontispiece of Erasmus looked nothing like Ed Wynn. My disappointment was part of growing up.

Seven years ago, when my parents moved from a large house to a small one, my brother and I divided the library overflow. My brother, who helped them pack, telephoned me from California, announcing each author as he emptied the bookcases. “Chekhov?” he asked. “Sure,” I replied. “Turgenev?” “Uh”—I was mentally gauging my shelf space—”I guess not.” Later, of course, I kicked myself for having spurned Turgenev. The four hundred volumes that passed to me (which included the Trollopes but, unfortunately, not

Fanny Hill

) were at first segregated on their own wall, the bibliothecal equivalent of a separate in-law apartment.

“You just don’t want your father’s Hemingways to be sullied by my Stephen Kings,” said George accusingly.

“That’s not true.”

He tried another tack. “Your father wouldn’t “want his books to be a shrine. Didn’t you say he used to let you build

castles

with them?”

This hit home. I realized that by keeping his library intact, I had hoped I might be able to keep my father, who was then eighty-six, intact as well. It was a strategy unlikely to succeed.

So his Trollopes are now ensconced in our Victorian section, cheek by jowl with our decaying college paperbacks. But I’ve been thinking of moving them to a lower shelf. Our two-year-old son is beginning to show an interest in building.

S

S

H A R I N G T H E

M

A Y H E M

W

hen Charles Dickens read aloud from

Oliver Twist

to a full house at St. James’s Hall, his heart rate shot up from 72 to 124, and no wonder. First he became Fagin. His friend Charles Kent, who watched from the wings, said that for several minutes Dickens resembled “the very devil incarnate: his features distorted with rage, his penthouse eyebrows … working like the antennae of some deadly reptile, his whole aspect, half-vulpine, half-vulture-like, in its hungry wickedness.” (It might accelerate anyone’s pulse to look like a reptile, a mammal, and a bird simultaneously.) Then, after glancing at the stage directions he had written in the margins (“Shudder … Look Round with Terror … Murder coming”), Dickens became Bill Sikes, wielding an invisible club. Finally, he became Nancy, gasping, “Bill, dear Bill!” as she sank to the floor, blinded by her own blood. After bludgeoning Nancy and hanging Sikes, Dickens prostrated himself on a sofa offstage, unable to speak in consecutive sentences for a full ten minutes.

When I read

The Story of a Fierce Bad Rabbit

to my son last night, there was no one around to check my pulse. However, Beatrix Potter and Charles Dickens seem to have attended the same Violent Writers School, and when I got to the part where the man with the gun blasts off the rabbit’s tail and whiskers (“BANG!”), I can tell you that Henry and I were both breathing pretty heavily. Private readings have certain advantages over public ones. We were both already prostrate, and had I been unable to speak in consecutive sentences, Henry never would have noticed. I was also able to insert editorial comments, such as “It wasn’t a

real

gun.” After describing “the pool of gore that quivered and danced in the sunlight,” Dickens could not turn to his audience—even though a physician had forecast mass hysteria among the women—and say, “It wasn’t

real

gore.”

We do a lot of reading aloud in our household. If you’re beginning to suspect that, like Dickens, we specialize in mayhem, I’m afraid you’re right. One morning last week, I emerged from the bedroom to find Susannah crunching her Rice Krispies while her father read to her from

Boy

, in which the young Roald Dahl gets caned (twice), has his adenoids removed without anesthesia, and nearly loses his nose in a car accident.

“Read me again about how his nose was hanging by just a little tiny string,” said Susannah.

Had I been a better mother, I would have said, “

After

breakfast.” Instead, I joined the audience. George was once a singing waiter, accustomed to linking dramaturgy and digestion, and he attacked the dangling nose with verve. I could see why he had raked in such big tips. I could also see, with breakfast-table clarity, the truth of something I had long suspected: that

all

readings are performances, with Dickens merely hogging the histrionic extreme of a spectrum shared by every parent who has ever lulled a child to sleep with

Grandfather Twilight

. When you read silently, only the writer performs. When you read aloud, the performance is collaborative. One partner provides the words, the other the rhythm.

No stage is required, no rehearsal, not even an audience. When he was a boy, Heine read

Don Quixote

to the trees and flowers in the Palace Garden of Düsseldorf. Lamb believed that it was criminal to read Shakespeare and Milton silently, even if no one was there to listen. During the second week of a college course in Greek, I was so thrilled by mastering the alphabet that I paced up arid down my dormitory room, regaling my furniture with hundreds of repetitions of the first two lines of the

Odyssey

:

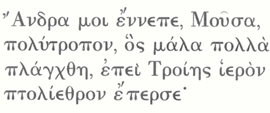

I recognized only two words—

Muse

and

Troy

—but it didn’t matter. Homer was meant to be spoken, and even though I had no idea what he was saying, I could hear the slosh of the wine-dark sea beneath each quavering dactyl.

Since the loss of his sight, my father has inhabited a Homerically aural realm. When I was a small child, he read to me constantly, specializing in Dr. Seuss. Many years later, while I was recovering from a tonsillectomy, he read me book 1 of

War and Peace

, with the result that I still associate all Russian names of more than three syllables with sore throats. Now I read to him. The generational table-turning was disorienting at first; I seemed the parent and he the child, but the child frequently corrected my pronunciation. The blind Milton did the same with his daughters, who read him Greek, Latin, Hebrew, Syriac, Italian, and French, none of which they understood. Eventually they grumbled so vehemently that they were sent out to learn embroidery instead. I read only in English, and I always enjoy it, except when I call my father with the obituary of one of his old friends. There’s no getting around the intimacy of reading aloud. He cannot grieve in private, the way he could if I mailed him the scissored page. As I hear him cough softly on the other end of the line, I plug doggedly toward the list of survivors and the location of the memorial service, knowing my voice is coming between him and his friend instead of bringing them together.

”

I

n reading aloud,” wrote Holbrook Jackson, “you are greatly privileged, first to consort with all that is noble and beautiful in thought and imagination, and then to give it forth again. You adventure among masterpieces and spread the news of your discoveries. No news better worth the spreading; few things better worth sharing.”

If the masterpiece you’re sharing is your own, you’d better be one hell of a reader. Dickens was; the tragic actor William Charles Macready assessed the “Sikes and Nancy” reading as worth “two Macbeths.” His listeners had to pony up several shillings, whereas we can hear celebrity authors read gratis at our local Barnes & Noble or, in the case of Jay McInerney, recently promoting a book called

Dressed to Kill: James Bond, the Suited Hero

, in the Saks Fifth Avenue men’s designer-clothing department. On the whole, I find public readings far less interesting than private ones. Who would not have wished to eavesdrop on Pliny, who entertained guests with his own work, or on Tolstoy, who often read his day’s output to his family? Or even on the endearingly narcissistic Tennyson, who once read

Maud

to the Brownings and a few other friends, stopping every few lines to murmur, “There’s a wonderful touch! That’s very tender! How beautiful that is!”