Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard (7 page)

Read Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard Online

Authors: Richard Brody

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Performing Arts, #Individual Director

In 1950, the CCQL showed a British film fantasy about a hypothetical conquest of Britain by the Nazis; in the middle of the screening, Frédéric Froeschel (the student who financed the CCQL) turned on the house lights and revealed a man standing before the audience in full Nazi military regalia and complaining loudly that he found the joke—the movie—in very bad taste; upon which the “officer” departed, the lights went out, and the screening continued.

The joker, Paul Gégauff, was a friend of Rohmer and Godard, and the nominal vice president of the CCQL. The joke in question derived from a costume party to which Gégauff was headed. He had in fact hoped to be accompanied to the gathering by a friend dressed in the striped clothing of a deportee and dragged at the end of a rope, but unsurprisingly, Gégauff found nobody willing to play along with him in this sordid game.

Born in 1922, Gégauff was a writer with a wartime past that he simultaneously sought to live down and boasted about: as a resident of Alsace, which Germany conquered and annexed, he was inducted into a Nazi youth organization, and wrote anti-Semitic articles for a local newspaper (a fact that was not revealed until after his death in 1983). Although never under suspicion for collaboration (indeed, Gégauff’s first novels, in 1951 and 1952, were published by Les Editions de Minuit, a publishing house that began during wartime as a clandestine Resistance publisher), Gégauff’s arch gestures seemed to confess to what he had not been accused of.

Gégauff led a flamboyant and sybaritic existence. He was said to have run through a lavish inheritance in two years of wild living.

64

Gégauff was a prodigious drinker and seducer. Indeed, his powers of seduction were the source of admiration among his associates; Charles Bitsch, who was one of the

members of the group from the CCQL, said that Gégauff “exerted a real fascination, especially on Godard and Chabrol.”

65

Claude Chabrol, another habitué at the CCQL and the Cinémathèque, diagnosed this fascination: “He [Godard] was in love with a girl and I think that Gégauff laid her without even trying. This shocked Jean-Luc, who was trying to go at things more slowly.” Chabrol described the resulting alignment: “Let’s say that on one side there was Momo [Rohmer],

66

Godard and Gégauff and on the other, Rivette and Truffaut. I made my way between these tendencies.”

67

Actor Jean-Claude Brialy recalled that only two people in film circles, beside himself, called Rohmer by the familiar “tu”: Godard and Gégauff.

68

According to Bitsch, Gégauff “wasn’t a rightist by political conviction but by the way he lived,” although Bitsch found it annoying that Gégauff “would say, very casually, ‘the Germans,’‘the Russians,’‘the Jews.’” According to Jacques Rivette, Gégauff “played the young fascist.”

69

As the official CCQL collaboration in Gégauff’s practical joke suggested, right-wing affectations were an integral part of the cinematic milieu that Godard frequented.

The CCQL was behind another, even more provocative, fascist practical joke, which rippled far beyond cinephile circles. On October 6, 1950, the club hired a sandwich-board man to advertise on the boulevard St.-Michel in the Latin Quarter its screening that night of

Jew Süss

, the notorious Nazi propaganda film from 1940, and outfitted him with a yellow star.

Although the film had previously been shown in film clubs without incident, the scandal-mongering advertising for the October 6 screening met with vehement protest from across the political spectrum. Hundreds of protesters from organizations of Jewish students, Christian students, Resistance veterans, Jewish survivors of concentration camps, and student members of the three major parties—Communist, Socialist, and MRP (centrist)—persuaded the police that it was in the interest of public order to cancel the screening.

70

The following week, a legislator in the National Assembly mentioned the intended screening of

Jew Süss

and other wartime propaganda films from Japan and Italy, asked the minister of the interior “to put a stop to it,” and demanded an inquiry into the club’s source of funds.

71

The band’s right-wing stunts and sympathies, so soon after the end of the German occupation, suggested a willful association with evil, a punk-like overturning of values. They also suggested the seemingly insurmountable distance between the young movie lovers and the official culture in which they desperately sought their place. Although they were, in practical terms, outsiders, intellectually they were insiders whose autodidactic fury suggested their craving for mastery of the canon. Godard’s own political provocations, which included his German pseudonym, Hans Lucas, and his article on political cinema, pointed to the underlying problem that the young future filmmakers of

the CCQL/Cinémathèque circle faced: despite their intellectual sophistication, they were condemned to anonymity, obscurity, marginality, unless they found a radical way to break into the French film industry, unless they found a way to attract attention.

Their method—the one that Godard himself undertook, at age nine-teen—was criticism. It was a singular method, which served two purposes, revolutionary and didactic. Godard and his young film-lover friends were learning how to make films by watching films; they were giving themselves a conservatory education at the Cinémathèque and the CCQL. By writing about the films they saw, they did two things: they elaborated and refined their ideas about the cinema, in anticipation of the day when they could make films; and they created for themselves a public identity that would get them the chance to make films.

But the November 1950 issue of

La Gazette du cinéma

—which featured Godard’s “16mm Chronicle” as well as his brief reviews of such films as Preston Sturges’s

The Great McGinty

, Robert Siodmak’s

The File on Thelma Jordan

, and the Danish

Ditte Menneskebarn

—proved to be the last: it sold too poorly to remain solvent, and for the time being, Godard and the other young enthusiasts around the CCQL had no outlet for their passion.

At that time, however, another publication was in the process of development. André Bazin would play a key role in its founding and editorial direction, and Rohmer would be an early contributor and elder statesman. Godard and his friends used this magazine,

Cahiers du cinéma

, as a base from which to launch their assault on the citadel of the French cinema. In the process, they changed the way that the French, and indeed the world, thought about movies, and helped to set in motion a generational shift that resounded far beyond their field of artistic endeavor.

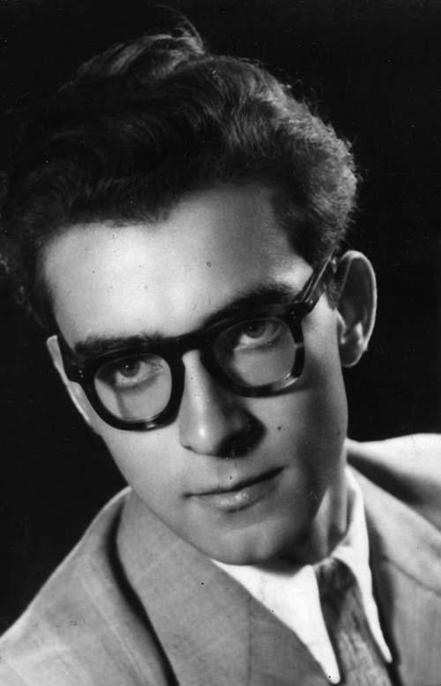

Godard, 1951

(Courtesy of Véronique Godard)

Two.

“A MATTER OF LOVING OR DYING”

O

N APRIL 2, 1950, JEAN GEORGE AURIOL, THE FOUNDER

of

La Revue du cinéma

, which had ceased publication in 1948,

1

died in a car accident. Jacques Doniol-Valcroze, one of its editors, resolved to revive it, with the principal collaboration of André Bazin, but its financial track record did not immediately attract new investors. However, in the fall of 1950, a film distributor and theater owner, Léonide Keigel, decided to invest in the venture. Gallimard, the former publisher of

La Revue

, refused to cede the use of the title, but gave Keigel the right to copy the defunct magazine’s format.

The first issue of the new monthly,

Cahiers du cinéma

, came out on April 1, 1951. Bazin, who was recovering from tuberculosis, was unable to participate in its day-to-day organization, and his name was left off the masthead of the first issue by Doniol’s coeditor, Joseph Lo Duca, a film critic whom Doniol-Valcroze had hired for his extensive experience as a professional editor. The magazine began with a fund of goodwill based on its resemblance to

La Revue

, both in content and in visual style—like its predecessor,

Cahiers

was published on glossy paper and featured many photographs along with its articles. And these articles were substantial, as the new magazine attracted writers of diverse stripes, including Alexandre Astruc, the “filmologist” Henri Agel, and mainstream film journalists such as François Chalais and Herman G. Weinberg.

Jean-Luc Godard missed these events because in December 1950 he had taken leave of Paris. As a French citizen, Godard was subject to the French draft. In order to escape combat in Indochina, he claimed Swiss citizenship and joined his father and younger sister, Véronique, on a trip to New York.

His father was leaving Switzerland and heading for Jamaica because his marriage to Godard’s mother had broken up, and his new clinic near Lausanne, Montbriant, had failed. Traveling by ship, Godard voyaged farther through Central and South America, stopping over in Panama, staying with relatives in Peru and Chile.

Godard’s Swiss friend Roland Tolmatchoff recalled that the trip’s proximate cause may have been the practical avoidance of French military service, but that its deeper inspiration was literary: “South America was because of [Jules] Supervielle,

L’Enfant de la Haute Mer

(The Child of the High Seas). It was very important for him, he talked about it a lot.”

2

Supervielle’s collection of stories, from 1931, presented a romantic view of South America.

Nonetheless, the romance of travel seems to have held little interest for Godard: a visitor who met him at his aunt’s house in Lima recalled that the young man was uninterested in exploring the country and was absorbed in his books and his thoughts.

3

Though the trip may have had an artistic inspiration, it did not inspire him to much output. He even had plans to make a film, but nothing came of them. According to Truffaut and Rivette, Godard’s return to Paris in April 1951 was accompanied by a change in his outward behavior. He was now taciturn. He barely said anything about the journey. Tolmatchoff’s impression of Godard’s reserve was even stronger: “I tried to speak with him about South America, but he didn’t say anything. It’s like a black hole, one wonders whether he really went. He did go, but I don’t know what he did there. I even looked through his passports which were lying around…but I didn’t find much.”

4

Upon his return to France, Godard threw himself back into helping others make films. In particular, he worked closely with Eric Rohmer on a short film that was conceived, written, and directed by Rohmer, but on which Godard nonetheless exerted a peculiar sort of authorship. Rohmer’s short film,

Présentation

(Introduction)—the same title as that of Sartre’s famous essay to inaugurate

Les Temps modernes

—was the first work in the professional, 35mm format by the young men from the CCQL and the Cinémathèque. It was built with and around Godard, who plays the lead male role of Walter, a young man who introduces one young woman to another in the hope of making each jealous of the other. One of them, Clara, is in a hurry and runs off. The other, Charlotte, is in a hurry too, but must return home for a moment, and Walter accompanies her. Because his shoes are wet and her kitchen floor is clean, she makes him drag the doormat indoors and stand on it—which he does the whole time he is at her home. Charlotte cooks herself a small steak and shares it with Walter (who remains rooted in place on the doormat). Their pointedly argumentative dialogue is ironic,

flirtatious, and arch: “Don’t you know that I love you very much” he asks. “You’re lying.” “Perhaps, but I’ll be faithful to you,” he says. She responds, “That’s idiotic; you know that I’m not.” “I want to be faithful to you. I’d like to be dead, so that you’d think of me.” “I’d think of you even less.”

Walter takes Charlotte’s face in his hands. They kiss, as she tells him that she does not love him and reminds him that he does not love her either. “Yes, I know,” Walter answers, “but am I not sad?” “No, you’re not, I’m sure of it. Come on, let’s go, you always make me late.” They leave Charlotte’s immaculate little kitchen and trudge through the snow to the station as Charlotte’s train arrives.

As he had done for Rivette, Godard paid for the film stock from his scant and dubiously gotten resources. He also helped Rohmer build the set for Charlotte’s kitchen in a photographer’s studio in Paris. Rohmer fondly recalled, years later, that Godard, who was young and athletic, had single-handedly lugged the refrigerator for the kitchen to the set (“I can still see Godard carrying it, falling over backwards”).

5

Yet Godard’s greatest contribution to Rohmer’s film was not practical but moral, and was achieved through his on-camera presence.