Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard (43 page)

Read Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard Online

Authors: Richard Brody

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Performing Arts, #Individual Director

A

RT, HOWEVER

, has structure and form; life by its nature is formless, or at least, its forms are hidden from the eye and revealed only through research and thought—precisely the sort of quasi-scientific abstractions that Godard had applied to cultural effluvia and managed to bring to the screen in

A Married Woman

. The result, however, was the one that Godard announced in the film’s credits: fragmentation. Godard explained to Guégan and Pétris that he had “abandoned [his] cinéphile habit”; he had left behind the model of the American cinema, which he now looked upon as an object of nostalgia. With no particular cinematic example or tradition to follow, Godard’s films would lack a structuring principle. Both he and life were on the other side of the screen; but where was the cinema?

A

T THE APOGEE

of Godard’s public renown, at the moment of his triumph as a cultural hero to the young and a new classic to his elders, he was increasingly lost as a filmmaker. He continued to make brilliant, personal films, even epochal films, and he did so at a furious pace that left his acolytes breathless. And yet, he would work with an increasing despair. Precisely as Godard’s engagement with “life”—political, social, intellectual—and with the new complexities and incipient crises of the times was intensifying, he was in doubt regarding the cinematic form with which to represent it. As his films became ever more permeable with regard to the explosive tensions and wild energies of the day, they also became increasingly formless. The summit of Godard’s fame and of his esteem as an artist and a cultural touchstone of the age was also the moment of his cinematic breakdown, which he displayed on-screen in real time.

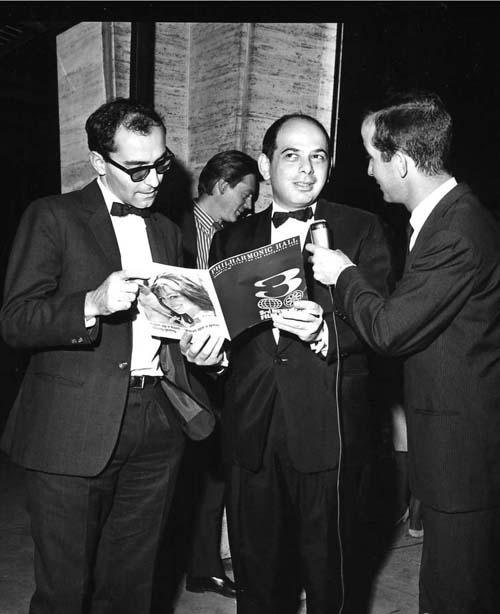

Godard and Richard Roud at the third New York Film Festival, 1965

(Film Society of Lincoln Center)

ten.

THE AMERICAN BUSINESS

A

S EARLY AS

J

UNE 1960, THE LITHUANIAN-BORN FILM

-maker Jonas Mekas, who was also the lead film critic for the New York

Village Voice

, wrote in

Cahiers du cinéma

that the New Wave was a strong influence on American directors. He cited as evidence the work of several independent filmmakers, including John Cassavetes. Mekas claimed that the French New Wave had taught young Americans to break taboos regarding so-called production values (i.e., the industrial sheen of the commercial cinema) and to tell stories of their own experience without regard to the conventions that marked the films of their elders. The “first-person” cinema that Truffaut had called for in 1957 had made rapid advances: in 1962,

Cahiers

critic Luc Moullet mentioned “German, English, Italian, American, Argentinian, Japanese, Russian, Polish, and even Spanish New Waves”

1

to which he might soon have added the Czechs and Brazilians.

But the New Wave’s most powerful effect came when its American acolytes assimilated the movement’s underlying critical position and sought a cinematic education similar to the immersion the New Wave filmmakers had undergone. The New Wave was not just a personal cinema of youth; it involved extensive reference to the history of cinema, and its resounding worldwide influence entailed a reorientation of taste. In the United States, this only happened when the

politique des auteurs

crossed the ocean, prompting American intellectuals to embrace the heritage of the Hollywood cinema.

2

At first, the New Wave’s admiration for seemingly routine thrillers, melodramas, comedies, and westerns by American directors—including Hitchcock,

Hawks, Nicholas Ray, Douglas Sirk, Anthony Mann, and Otto Preminger—baffled most intellectuals, critics, and even industry professionals in the United States, who considered these films merely popular commercial entertainments. But a few energetic film programmers relying on the advice of a few good critics, as well as by the farsighted support of a few large cultural institutions, spurred a change in attitude. Primarily, the shift took hold among young intellectuals and artists, largely through the work of one tireless proselytizer, Peter Bogdanovich, and the writing of one critic, Andrew Sarris.

Bogdanovich, a young actor and precocious film buff (born in 1940), had two pulpits from which to preach: he helped Daniel Talbot, the programmer at the New Yorker Theatre, organize revivals of classic American films. At age twenty, he also had a radio show called

The Film Scene

. In 1960 the Museum of Modern Art asked Bogdanovich to organize an Orson Welles retrospective for the following year. Then, under the personal influence of Sarris as well as Eugene Archer of the

New York Times

, he programmed for Talbot two series of “Forgotten Films”—forgotten because they had been critical failures—which included such now-canonical classics as Hawks’s

Bringing Up Baby

and

Rio Bravo

, Hitchcock’s

The Wrong Man

, Max Ophüls’s

Letter from an Unknown Woman

, and Ray’s

Johnny Guitar

. These series were great successes and brought Bogdanovich commissions from the Museum of Modern Art to organize a six-month Hawks retrospective in 1962 and a similarly comprehensive Hitchcock retrospective in 1963; both were widely heralded and well attended.

New York audiences, which had embraced the first films of the French New Wave, now began to turn their attention to the movies that had inspired them. But just as the postwar Parisian taste for popular American films had been galvanized into a polemical line by the young

Cahiers

critics, New York’s newfound enthusiasm for the classic American cinema found its clarification and defense in the critical discernment and audacity of Andrew Sarris.

Born in 1928, Sarris was a film critic alongside Mekas at the

Village Voice

when, having familiarized himself from afar with the writings and films of the

Cahiers

group, he went to Paris in 1961. There he met New Wave directors and saw their films. He recognized the merits of the

Cahiers

agitations on behalf of American directors who had been so overlooked or dismissed at home. He was also present for the release of the surprising New Wave works that were inspired by them, such as

Shoot the Piano Player

and

A Woman Is a Woman

. As Sarris later described the experience, “I began seeing a lot of American movies through French eyes… To show you the dividing line in my thinking, when I did a Top Ten list for the

Voice

in 1958,

I had a Stanley Kramer film on the list and I left off both

Vertigo

and

Touch of Evil

.”

3

When Sarris returned to the United States, he brought to his American readership the enthusiasms he had cultivated in Paris. He wrote “a very

Cahiers du cinéma

review of

Psycho

,” which received “a tremendous amount of hostile mail. The

Voice

had all these readers—little old ladies who lived on the West Side, guys who had fought in the Spanish Civil War—and this seemed so regressive to them, to say that Hitchcock was a great artist.”

4

He decided to write an essay to introduce and defend the

politique des auteurs

. This in itself was a bold move. François Truffaut himself had never written the theoretical exposition of the

politique des auteurs

that he had promised

Cahiers

throughout the mid-1950s. Sarris’s effort was even more daring: to satisfy himself that his essay was intellectually honest, he conceived and wrote it as a response to the antiauteurist essays of the

politique

’s most profound detractor and the man he considered the greatest film critic of all time, André Bazin.

The “little magazine”

Film Culture

, published and edited by Jonas Mekas, included Sarris’s “Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1962” in its Winter 1962–63 issue.

5

In it, Sarris rightly admitted that his essay was “less a manifesto than a credo.” He recognized that the underlying premise to what he called the “theory” (“auteur theory” being his own translation of the

politique des auteurs

) was one of taste: “These propositions remain to be proven and, I hope, debated. The proof will be difficult because direction in the cinema is a nebulous force in literary terms.”

Sarris was offering an overview of the

politique

rather than an analysis of the films which inspired him to endorse it, and his essay is less a work of criticism than a prologue to future criticism. In his essay, he asserts the practical import of the

politique

for working critics: “Just a few years ago, I would have thought it unthinkable to speak in the same breath of a ‘commercial’ director like Hitchcock and a ‘pure’ director like Bresson.” He continues:

After years of tortured revaluation, I am now prepared to stake my critical reputation, such as it is, on the proposition that Alfred Hitchcock is artistically superior to Robert Bresson by every criterion of excellence, and, further, that, film for film, director for director, the American cinema has been consistently superior to that of the rest of the world from 1915 through 1962. Consequently, I now regard the auteur theory primarily as a critical device for recording the history of the American cinema, the only cinema in the world worth exploring in depth beneath the frosting of a few great directors at the top.

For Sarris, the auteur theory served the same purpose that it served his French counterparts: to fight for the recognition of the great Hollywood directors working within the structures (or strictures) of the studio system as the equals of the greatest directors working anywhere; and for the recognition of the cinema’s artists as the equals of artists working in the traditional art forms. He offered three premises on which the theory rested:

- It is not a cult of personality, but a synoptic view of existing work—a guide to film history rather than a cheat sheet for judging new works in advance: “What is a bad director, but a director who has made many bad films?”

- It asserts “the distinguishable personality of the director as a criterion of value”—here Sarris argued for applying critical intelligence to Hollywood fare in order to discover the personal signature of filmmakers who were generally thought not to have one.

- It “is concerned with interior meaning, the ultimate glory of the cinema as an art. Interior meaning is extrapolated from the tension between a director’s personality and his material.” Sarris explains his quasi-mystical concept as “not quite the vision of the world a director projects nor quite his attitude toward life. It is ambiguous, in any literary sense, because part of it is imbedded in the stuff of the cinema and cannot be rendered in noncinematic terms.” He attempts to capture this artistic essence with an uncharacteristically flamboyant aphorism: “Dare I come out and say what I think it to be is an élan of the soul?”

Here, Sarris’s view echoed that of the French New Wave critics: he did not merely assert the equality of cinema to other arts, but suggested that there was something about cinema that distinguished it from the other arts. For Godard it was montage, for Rohmer it was the art of space; for Rivette it was “mise-en-scène.” Overall, the

Cahiers

group—and especially Godard, who had made so much of the quasi-mystical thrall that the cinema induces (“at the cinema, we do not think, we are thought”)—had not merely praised certain unrecognized directors, they had exalted the cinema as the preeminent modernist art form.

Sarris was caught in a difficult trap: although he could transfer Hitchcocko-Hawksian taste to the United States and and get his compatriots to see American movies through “French eyes,” he could not reproduce the context in which those visions were expressed. First, Sarris did not write with

the polemical aggression of the

Cahiers

critics, who commanded attention through their vehement attacks on the mainstream French cinema. Second, where the

Cahiers

critics were preparing the terrain for their own art, Sarris asserted the theory as a historical program, as a school for critics. Although he endured as much public opprobrium for his ideas as had the French pioneers, Sarris could not promise, as those critics did, to deliver the films that would confirm them.

6

While André Bazin’s objections to auteurism were tempered by his personal respect for the young critics at

Cahiers

, Sarris’s detractors had no such inhibitions. The most talented and least temperate of them was Pauline Kael. In the early 1960s, Kael (who was born in 1919), lived in California. She wrote for a wide range of publications, from the popular (

Mademoiselle

and

Holiday

) to the serious (

The Atlantic Monthly

), and also did radio broadcasts. She responded to Sarris, in the spring 1963 issue of

Film Quarterly

, with a diatribe, “Circles and Squares” (referring to his incidental notion of three “circles” of directorial achievement), in which she argued with sarcastic condescension that the auteur theory was “a mystique, and a mistake.”