Everything Beautiful Began After (12 page)

Read Everything Beautiful Began After Online

Authors: Simon Van Booy

“This is my dream home,” George said, trailing Henry through the stacks toward a battered chaise.

“It’s like a museum, isn’t it, George?”

“A museum that should be in a museum,” George said.

“Don’t mind the stuffing,” Henry said, when they reached the chaise. “This couch once belonged to a princess of Poland whom the professor said he was in love with.”

“So how did he end up with her chaise?”

“Who knows,” Henry said. “I can’t imagine Professor Peterson with a woman unless she’s been mummified.”

“Nice you spend so much time together,” George said.

“Well, we work together.”

“That’s even better.”

“What was he like growing up?”

“Growing up?”

“Did your mother come along too?”

“My mother?”

“To the archaeological sites, I mean,” George said ardently.

“No,” Henry said, quite confused. “My mother never came to work with me.”

“So it was just you and your father.”

Henry laughed. “Professor Peterson is not my father, George.”

“He’s not?”

“Well, in a way—he’s like my second father.”

“It shows,” George said, looking around the room. “Don’t suppose you have anything to drink here?”

Henry eyed him with mild scorn. “Well, perhaps after I’ve patched you up. The professor has some single malt somewhere.”

George sat on the battered chaise.

“If you want me to look at your knees you’d better take your trousers off.”

George quietly undressed.

“I’ll unbutton my shirt too,” George said. “I have a feeling my back is grazed.”

“Okay.”

“Is my nose bleeding?”

“It doesn’t look like it.”

George stripped down to his pinstriped boxer shorts, but kept on his black oxford shoes, black socks, and sock garters. Henry opened a rusty tin box with a red cross on it and removed pads, gauzes, swabs, and disinfectant. Then he gently felt the area on George’s leg where the wound was.

“There’s actually quite a bit of swelling,” Henry said. “But I don’t think we need to have an X-ray—unless you’re really in a terrible mess and hiding it from us.”

“A terrible mess?”

Henry peered up at him.

“Are you in a terrible amount of pain, George?”

George hesitated.

“Not really,” he said.

“Then I’ll just clean and bandage.”

“How do you know all this?” George asked.

“Two terms at medical college spent looking at bodies.”

“So you’ve had more than a first-aid course.”

“Yes I have—the professor likes his jokes though.”

As he wrapped the bandage around George’s knee, the sensation of Henry’s hand brushing his leg slowed George’s breathing. There was such tenderness in Henry’s hands that George felt quite giddy and had no memory of falling asleep.

When George opened his eyes, Henry was staring at him from a chair he had placed next to the chaise.

“What were you dreaming about?” Henry asked.

“I didn’t even know I was asleep,” George said, struggling to sit up.

Henry switched on a few floor lamps, and then cooked some Greek coffee on the professor’s rusty stove. When the coffee was ready, Henry looked for the professor’s single malt and then poured some into their coffee cups.

“You’re not here with the American School of Archaeology?” Henry asked quietly.

“No,” George said. “I graduated two years early from university and wanted to get a head start on my PhD.”

“Where are you from in America?” Henry said.

“Morris County, Kentucky,” George said. “Originally. Very pretty if you like woods and meadows.”

And then Henry asked George to tell him more. George spoke in a soft voice. Henry closed his eyes to imagine trees swaying, clear rivers, and then summer—an unbearable heat, green wilderness packed with the tightness of a fist.

“Sounds like paradise,” Henry said.

“It’s close to it,” George said. “But I spent most of my childhood at boarding school in the Northeast.”

“They have boarding schools in the States?” Henry asked.

“Oh yes,” George said. “With uniforms and everything.”

Henry pointed toward George’s ankles. “I like your sock garters. I have a pair too, somewhere.”

George asked for more scotch.

Henry brought the bottle back to the chaise. He took a swig and then passed it to George, who took a long drink.

“So what do you do here, George?”

“Apart from drink and get my heart broken?”

“And get run over,” Henry added.

“I’m exploring the vast field of ancient languages.”

“Interesting,” Henry muttered, suddenly preoccupied. “Can I show you something?” He rushed over to the professor’s desk and found a paper copy of the script written on the professor’s discus.

He handed it to George. “Can you make any sense of this?”

George scrutinized it for a minute. “Honestly?”

“Yes, honestly.”

“No,” George said.

Henry looked disappointed.

“Because it looks like Lydian,” George said. “And that’s very hard to translate.”

As the afternoon light deepened into gold, the two men leafed silently through centuries-old dictionaries in a bid to translate the text before the professor returned.

Henry switched on the radio, and the turning of pages was accompanied by the crackle of Haydn’s

La Fedeltà Premiata

. They moved only to smoke and drink coffee.

The translation would have taken much less time had George and Henry not been constantly sidetracked by interesting but unrelated chapters, which they felt compelled to share with one another.

The sentences and paragraphs that Henry found interesting George copied into his orange notebook.

George liked to read his digressions aloud without looking up from the page.

Henry listened. The sound of George’s voice made him feel as though he were drifting above his life.

When he opened his eyes, the recitation had ceased.

“It’s like we’re long lost brothers,” George said.

When the professor burst in an hour later, he found George and Henry asleep on the chaise. George was sitting upright, while Henry lay partially upon George, using his shoulder as a pillow.

George was the first to wake up. The professor stared down at him superciliously. He was holding George’s translation that Henry had pinned to the door.

“I hope, George,” Professor Peterson said, lighting his pipe, “that you don’t have any plans tomorrow.”

“Tomorrow?”

Then Henry woke up.

“Thought you might like to see the dig where you’ll be working from now on,” the professor went on, puffing out smoke.

The tobacco sizzled.

“Where I’ll be working?” George said.

“Excellent,” Professor Peterson said. “It’s all settled then. Welcome to the family.”

Rebecca and the topless man stood facing one another in the hall. It was very hot. The skin on his chest and shoulders glistened. Rebecca set down her backpack and easel.

“Do you speak English?” she said. “French?”

She hoped he might motion her inside again.

“

Liga,

” he said, finally. “Speak little English. What do you want?”

Rebecca explained that she was a friend of the foreigner for whom he had left the fish. She said that she was an artist and wanted to draw him.

From the short time she had lived in Athens, she had learned that there is little point in trying to deceive a Greek. It was an art they had perfected even before their victory at Troy.

Rebecca explained how she’d seen him from the window. He didn’t seem angry or saddened by her request but just stood very still gazing at her. He had walked down the backs of his sandals. The radio was on in his apartment and played some ancient opera.

“You real artist,” he said in a way that wasn’t clear whether he meant it as a statement or a question. But then he moved aside for her to enter and she did.

His apartment was empty but for a few straw chairs, an old television with thick dust on the glass, and an industrial broom. The radio sat on top of the television. Clean folded towels were stacked on a table in one corner, and on a chair were slung several dirty towels. From the kitchen she could hear bubbling. Rebecca wondered whether she should ask why he boils towels when he suddenly explained how the towels were from a nearby hospice, and that after someone died, the towels needed to be boiled clean.

He asked her to sit down by pointing at a chair. Then he went into the kitchen. The faucet squeaked. He returned with a glass of water.

“

Nero,

” he said.

He tilted his head to one side as she drained the glass. Then he took the glass back to the kitchen. The walls of his room were yellow with cigarette smoke. The only single piece of decoration was a painting hung beside the window—a reproduction of Munch’s

The Storm.

A white, veiled figure running from dusk into wilderness. This man’s life, Rebecca felt—is a slow plummet.

Pain drawn out by thought.

He returned with a second glass of water. She took a gulp and put it down. He watched. Then he asked where she was from and about her childhood. She said: “My mother abandoned us.” He shrugged. “Tell me a nice moment,” he said. “Remember something nice for me and I’ll let you paint me.”

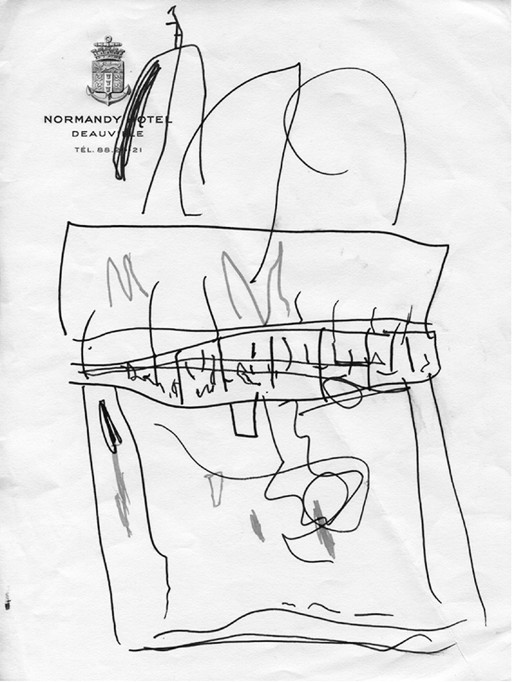

And so she let herself fall back through the past, until her memory with seeming randomness pulled a postcard from her life, and she told the story of an old piano she and her sister found washed up on a beach. They were bright little girls then, vacationing with their grandfather in rainy Deauville. The next day the piano had gone, carried back out to sea on the tide. She was especially upset. Later that night her grandfather found some paper and told her to draw it, to bring it back with her memory.

Rebecca’s drawing of a piano that washed up. Age 6.

The topless man motioned with his hands upon an imaginary keyboard and then lit a cigarette. Then he offered the pack to Rebecca, and they smoked together.

As Rebecca set up the easel and unpacked her pencils, she noticed her fingers were trembling.

He remained naked from the waist up, and his flesh hung lazily from muscles that still bore the frame of muscular youth, like something beautiful in the early stages of decay. His face was poorly shaved. His cheekbones were high, almost regal.

After an hour of silence, he asked if he could smoke again. Rebecca put down her pencil and they both lit cigarettes.

“I unlucky,” he said.

“What do you mean?”

“Tragic things happen.”

“I understand,” she said. Her tragedy had been slow, whereas his needed only a few seconds.

“It was my fate,” he said.

“I’m sorry for you,” Rebecca said.

“Yes,” he said. “Like Oedipus—it was my fate.”

He lit another cigarette.

“You cannot change fate,” he added.

Rebecca nodded.

“It’s set, you understand? Like the weather.”

Rebecca nodded again and raised her eyebrows as if she had just understood. He seemed pleased and went into the kitchen, where he began feeding towels into hungry pans of boiling water. He returned after a few minutes and sat back down.

“I’m ready,” he said.

Rebecca told herself that she did not believe in fate. She believed that she alone was responsible for everything that happened to her. If there was such a thing as fate, she thought, her mother would be blameless. It would have been her fate to abandon her daughters.

But it was not her fate.

It was her decision.

Fate is for the broken, the selfish, the simple, the lost, and the forever lonely—a distant light comes no closer, nor ever completely disappears.

The topless man was a good subject, except for the occasional twitch the way a person does when falling asleep. After two more hours, he held an invisible cigarette up to his lips.

“Smoke?”

“Yes,” she said. “Smoke, I’m almost finished.”

Rebecca dabbed the sweat from her face with a linen scarf. He did not sweat, though his skin maintained a constant level of moisture that contrasted with the hard black of his hair.

The man held his cigarette by the neck as though it were an insect he had caught. When the paper and tobacco had burned away, he didn’t stub it out, but just lay it flat in the saucer he was using as an ashtray.

After a few final strokes, Rebecca motioned for him to come around to her side of the picture.

“No,” he said, shaking his finger.

“But don’t you want to see how I’ve drawn you?”

“No,” he said. “You see any mirrors in here?”

Rebecca looked around, embarrassed by her sudden vanity.

She removed the paper and sprayed it with a substance that would ensure it didn’t smudge. Then she packed away the easel. The man fetched her a fresh glass of water.

“You come back if you want to draw me again.”

“I will,” she said.

“Okay,” he said.

He made her promise that she would come back.

As she was leaving, he put his hand upon her shoulder. Then he took it off.

“Wait,” he said. He ran back into the apartment. Rebecca was holding the front door. She heard the slamming of cupboard doors and he was suddenly back.