Everything Bad Is Good for You (8 page)

Read Everything Bad Is Good for You Online

Authors: Steven Johnson

It would probably take you a lifetime to read all the transcripts of comparable debates, both online and off, that follow in the wake of these shows. The spelling isn't perfect, and the grammar occasionally leaves something to be desired. But the level of cognitive engagement, the eagerness to evaluate the show through the lens of personal experience and wisdom, the tight focus on the contestants' motives and character flawsâall this is remarkable. It's impossible to imagine even the highbrow shows of yesteryearâmuch less

The Dukes of Hazardâ

inspiring this quantity and quality of analysis. (There are literally hundreds of pages of equivalent commentary at this one fan site alone.) The unique cocktail that the reality genre serves upâreal people, evolving rule systems, and emotional intimacyâprods the mind into action. You don't zone out in front of shows like

The Apprentice.

You play along.

The content of the game you're playing, admittedly, suffers from a shallow premise and a highly artificial environment. (Plus the show forces you to contemplate Donald Trump's comb-over on a regular basis, occasionally windblown.) This is another way in which the reality shows borrow their techniques from the video games: the content is less interesting than the cognitive work the show elicits from your mind. It's the collateral learning that matters.

Part of that collateral learning comes from the sheer number of characters involved in a show like

The Apprentice

or

Survivor.

Just as

The Sopranos

challenges the mind to follow multiple threads, the reality shows demand that we track multiple

relationships,

since the action of these shows revolves around the shifting feuds and alliances between more than a dozen individuals. This, too, activates a component of our emotional IQ, sometimes called our social intelligence: our ability to monitor and recall many distinct vectors of interaction in the population around us, to remember that Peter hates Paul, but Paul likes Peter, and both of them get along with Mary. This faculty is part of our primate heritage; our closest relatives, the chimpanzees, live in societies characterized by intricate political calculation between dozens of individuals. (Some anthropologists believe that the explosion in frontal lobe size experienced by

Homo sapiens

over the past million years was spurred by the need to assess densely interconnected social networks.) Environmental conditions can strengthen or weaken the brain's capacity for this kind of social mapping, just as it can for real-world mapping. A famous study by University College London found that London cabdrivers had, on average, larger regions in the brain dedicated to spatial memory than the ordinary Londoner. And veteran drivers had larger areas than their younger colleagues. This is the magic of the brain's plasticity: by executing a certain cognitive function again and again, you recruit more neurons to participate in the task. Social intelligence works the same way: spend more hours studying the intricacies of a social network, and your brain will grow more adept at tracking all those intersecting relationships.

Where media is concerned, this type of analysis is not adequately illustrated by narrative threads or a simple list of characters. It is better visualized as a network: a series of points connected by lines of affiliation. When we watch most reality shows, we are implicitly building these social network maps in our heads, a map not so much of plotlines as of attitudes: Nick has a thing for Amy, but Amy may just be using Nick; Bill and Kwame have a competitive friendship, and both think Amy is using Nick; no one trusts Omarosa, except Kwame, but Troy

really

doesn't trust Omarosa. This may sound like high school, but like many forms of emotional intelligence, the ability to analyze and recall the full range of social relationships in a large group is just as reliable a predictor of professional success as your SAT scores or your college grades. Thanks to our biological and cultural heritage, we live in large bands of interacting humans, and people whose minds are skilled at visualizing all the relationships in those bands are likely to thrive, while those whose minds have difficulty keeping track are invariably handicapped. Reality shows force us to exercise that social muscle in ways that would have been unimaginable on past game shows, where the primary cognitive skill tested was the ability to correctly guess the price of a home appliance, or figure out the right time to buy a vowel.

The trend toward increased social network complexity is not the exclusive province of reality television; many popular television dramas today feature dense webs of relationships that require focus and scrutiny on the part of the viewer just to figure out what's happening on the screen. Traditionally, the most intricate social networks on television have come in the form of soap operas, with affairs and betrayals and tortured family dynamics. So let's take as a representative example an episode from season one of

Dallas.

The social network at the heart of

Dallas

is ultimately the Ewing family: two parents, three children, two spouses. A few regular characters orbit at the periphery of this constellation: the farmhand Ray, the Ewing nemesis Cliff. Each episode introduces a handful of characters who play a onetime role in that week's plotline and then disappear from the network. In this episode, “Black Market Baby,” the primary structure of the narrative is a double plot: the competition between the two brothers to have a baby and give the family patriarch a long-overdue grandchild. Imagined purely in narrative termsâalong the lines of our

Sopranos

and

Hill Streetâ

this would be a relatively simple structure: two plotlines bouncing back and forth, overlapping at a handful of key moments. But viewed as a social network, it is a more nuanced affair:

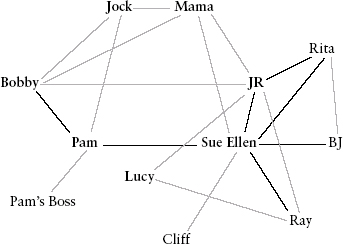

The lighter lines represent a social relationship that you must grasp to make sense of the episode's plot: you need to understand that the patriarch Jock doesn't approve of Pam's decision to go into the workforce and delay having a baby, just as you need to understand the longstanding rivalry between Bobby and JR in several crucial scenes with the entire family. The darker lines represent social relationships that trigger primary narrative events: when JR intervenes to pay the surrogate mother Rita to leave the state, thereby squelching Sue Ellen's adoption plan, or when Sue Ellen has a drunken night of passion with Ray.

Most of us don't think of these social networks in explicitly spatial terms while we watch TV, of course, but we do build working models of the social universe as we watch. The visualizations help convey in a glance how complex the universe is. And a glance is all you need to seeâin the bellow chart, of a season-one episode of the FOX series

24â

that something profound has happened to the social complexity of the TV drama in the past thirty years.

Season one of

24

is ultimately a narrative web strung between four distinct families: the hero Jack Bauer and his wife and daughter; the family of the threatened senator, David Palmer; the family of the Serbian terrorist Victor Drazen; and the informal family of coworkers at the Central Terrorism Unit, where Bauer works. (This last functions as a family not just because they live in close quarters together, but also because the office dynamics include two significant romantic dalliances.) Again, I have represented social connections that are relevant to the episode's plot in the lighter lines, and relationships crucial to the plot in darker lines. By every conceivable measure,

24

presents at least three times as complex a network as

Dallas

: the number of characters; the number of distinct groups; the connections between characters, and between groups; the number of relationships that are central to the episode's narrative. The social world of

Dallas

is that of an extended family: the primary players are direct relatives of one another, and the remaining characters have marginal roles.

24,

on the other hand, is closer to the scale of a small village, with four rival clans and dozens of links connecting them. Indeed, the social network of

24

mirrors the social network you frequently encounter in the small-town or estate novels of Jane Austen or George Eliot. The dialogue and description are more nuanced in those classic works, of course, but in terms of the social relationships you need to follow to make sense of the narrative,

24

holds its own.

Watch these two episodes of

Dallas

and

24

side by side and the difference is unavoidable. The social network of

Dallas

is perfectly readable within the frame of the episode itself, even if you haven't seen the show before and know nothing of its characters. The show's creators embed flashing arrows throughout the opening sequenceâan extended birthday party for the family patriarch, Jockâthat laboriously outline the primary relationships and tensions within the family. Keeping track of the events that follow requires almost no thought: the scenes are slow enough, and the narrative crutches obvious enough, that the modern television fan is likely to find the storylines sluggish and obvious. Watch

24

as an isolated episode and you'll be utterly baffled by the events, because they draw on such a complex web of relationships, almost all of which have been defined in previous installments of the series. Appropriately enough for a narrative presented in real time,

24

doesn't waste precious seconds explaining the back story; if you don't remember that Nina and Tony are having an affair, or that Jack and David collaborated on an assassination attempt against Drazen, then you'll have a hard time keeping up. The show doesn't cater to the uninitiated. But even if you

have

been following the season closely, you'll still find yourself straining to keep track of the plot, precisely because so many relationships are at play.

The map of

24'

s social network actually understates the cognitive work involved in parsing the show. As a conspiracy narrativeâand one that features several prominent “moles”âeach episode invariably suggests what we might call phantom relationships between characters, a social connection that is deliberately not shown onscreen, but that viewers inevitably ponder in their own minds. In this episode of

24,

Jack Bauer's wife, Teri, suffers from temporary amnesia and spends some time under the care of a new character, Dr. Parslow, about which the viewer knows nothing. The show offers no direct connection to the archvillain, Victor Drazen, but in watching Parslow comfort Teri, you compulsively look for clues that might connect him to Drazen. (The same kind of scrutiny follows all the characters at CTU, because of the mole plot.) In

24,

following the plot is not merely keeping track of all the dots that the show connects for you; the allure of the show also lies in weighing

potential

connections even if they haven't been deliberately mapped onscreen. Needless to say,

Dallas

marks all its social relationships with indelible ink; the shock of the “Who shot JR?” season finale lay precisely in the fact that a social connectionâbetween JR and his would-be assassinâwas for once

not

explicitly spelled out by the show.

Once again, the long-term trend of the Sleeper Curve is clear: one of the most complex social networks on popular television in the seventies looks practically infantile next to the social networks of today's hit dramas. The modern viewer who watches

Dallas

on DVD will be bored by the contentânot just because the show is less salacious than today's soap operas (which it is by a small margin) but because the show contains far less

information

in each scene. With

Dallas,

you don't have to think to make sense of what's going on, and not having to think is boring.

24

takes the opposite approach, layering each scene with a thick network of affiliations. You have to focus to follow the plot, and in focusing you're exercising the part of your brain that maps social networks. The content of the show may be about revenge killings and terrorist attacks, but the collateral learning involves something altogether different, and more nourishing. It's about relationships.