Eva (27 page)

The seat!

Quickly he took out his knife and with a single cut slashed open the saddle. He pried the leather apart. Inside was a compact stuffing of spongy rubber. Nothing else.

The woman was staring at him, her mouth half open, her eyes wide. Unconsciously she tried to moisten her dry lips with her tongue.

Woody gave the saddle a forceful wrench and twisted it off the seat tube. He peered into the hollow frame. A couple of inches below the rim—leaving only enough space to give the saddle pin a purchase—a string was taped to the inside of the steel tube. With a finger he fished it up. He hauled it out. Attached to it was roll after roll of tightly wound new $100 bills!

He had found the further product of Operation Birch Tree!

He looked at the two bikes. He had no doubt the hollow frames of both of them were stuffed with U.S. currency. Forged, of course. But so masterly executed that only an expert might detect it.

The damned bikes

were

worth their weight in gold, he thought wryly. And they

had

just exploded in the faces of Herbert and Gertrud Kotsch.

He glanced at them. They stood frozen, chalk-faced, staring at the bikes.

It suddenly all made sense.

Gertrud and Herbert Kotsch were skipping out. Absconding with the funds given to them by their organization for dispersement to escape route travelers, hoping to be able to disappear with their loot in the chaotic aftermath of the war. Sterling characters. No wonder they had been willing to sacrifice their paltry souvenirs.

They had their own little personal fortune. It was their anxiety over that which he had detected. That was what had been nagging him all along.

He smiled sardonically at Kotsch. “Well,

Herr Oberst,”

he said. “It looks as if this leg of the

B-B Achse

will be without funds for awhile.”

Kotsch remained silent.

“Consider yourself lucky,” Woody went on. “The forgeries are good. Damned good. But sooner or later you would have been caught. And would have had to pay the price.” He regarded the man speculatively. “You will, of course, have to be tried by the Military Government courts—you and your wife. You will, of course, be placed in a Detention Camp. Probably near Halle.” He looked at the bikes. He sighed. “I will do my best to ensure your safety there,” he said. “But—I can promise nothing.”

Kotsch looked up. “Safety,” he frowned. “Promise? I do not know what you mean.”

“Oh, it’s quite simple,

Herr Oberst,”

Woody explained guilelessly. “The Halle Detection Camp is like the other camps. Internal security is provided by the internees themselves.” He looked pityingly at the Kotsches. “Once they learn that you tried to defraud your organization—betrayed the Reich, as it were—running off with their money given you in trust, your safety may be endangered. I . . .”

“We did not!” Kotch burst out. “Our orders . . .”

“But will your fellow internees know that?” Woody asked. “Will they believe you—or the evidence?” He glanced at the bikes.

Kotsch clamped his mouth shut. He knew the answer.

“Unfortunately,” Woody went on, “unfortunately we have had a few rather messy cases like this before. And there

are

other internees at the Halle camp who worked in organizations such as yours.” He shrugged. “They may take actions that—I’m sure you understand,

Herr Oberst

—that are difficult if not impossible for us to control.”

The Kotsches looked soberly at one another, fear pinching their faces. Gertrud instinctively moved closer to her husband.

“Of course,” Woody said tentatively, “no one at the camp need know of your—eh—temporary lapse of discretion. I could keep that between us.”

Kotsch looked at him. “For a price, I take it,” he said bitterly.

Woody could almost see the wheels spin in the German’s head. He would rather take his chances with his enemies than with his own kind.

“For a price,” he nodded.

Kotsch sighed. He clutched his wife’s arm.

“The address is Bebelgasse 49,” he said tonelessly. “In Eisenach.”

“And the password?”

“

Baumannshöhle.”

“Countersign?”

“

Hermannshöhle.”

Woody turned to Kowalski. “Corporal,” he said, “you will take the prisoners—and their bikes—with you when you return to your unit.”

“Yes, Sir.”

“I will write a report and forward it to your CO.” He turned to Kotsch. “Just one more thing,

Herr Oberst,”

he said. “I want to see where that young couple was hidden.”

Kotsch shrugged. “I no longer have the key,” he said.

“Don’t worry,” Woody assured him. “We’ll manage.” He motioned to Kowalski. “Corporal, you come with us.”

The lock on the door to

Baumannshöhle

yielded to the second blow of Kowalski’s gun butt. By the light of the carbide lamps the three men descended into the caverns below. They made their way through the halls and chambers, past contorted pillars of stone and glistening stalactites and stalagmites, marveling at the spectacularly gnarled and craggy rock formations. They squeezed through the narrow opening at the end of the public caves, negotiated the tight corridor, and finally stood in the chamber that had been the hiding place for the

B-B Achse

travelers.

Woody looked around. Two cots, folded, stood leaning against the wall. A pile of German army blankets lay next to them, as well as several books. At the opposite end of the cave stood a few still-sealed crates and cardboard boxes, and several more open ones, some filled with debris, torn rations wrappings, and empty food and carbide cans. Woody walked over to the trash boxes. He tipped one of them over. The trash spilled out onto the rocky floor: the crumpled paper, empty cans, and a deck of well-worn playing cards as well as other refuse. He overturned another with more debris and rubbish, and another. In the trash was a small piece of dirty, white cloth. He picked it up. It was a small handkerchief spotted with what looked like dried blood.

He looked closely at it.

In one corner were embroidered the initials

EB.

He had found his proof.

Eva Braun

was

alive.

16

Y

OU’RE

AWOL!” Major Hall growled at Woody as he walked into the CIC office. It was just after 0800 hours, Tuesday, June 5. “You were supposed to report back here yesterday, dammit!”

“I know, I know, Mort.” Woody put up a defensive hand. “But . . .”

“I could throw the damned book at you.”

“But you won’t,” Woody said. “Not after you’ve heard what I have to report.”

Hall looked speculatively at the young agent. Something was obviously up. Something important. He’d only given lip service to his annoyance when he made his AWOL threat. Hell, CIC work was too damned flexible to bother with that kind of crap. But, dammit, Woody should have at least reported in. He’d actually worried about him gallivanting about outside his jurisdiction on some wild goose-step chase. He did not like to worry about his boys.

“It had better be good,” he grunted.

“It is,” Woody quietly assured him.

Quickly, concisely he told his CO of his interrogation of the Bocks in Halle; his tracking down of the Kotsches in Rübeland; their admissions; and his finding of the

EB

handkerchief. Hall listened to it all without interrupting him.

“Eva

is

alive, Mort,” Woody finished. “I know it in my guts.”

Hall nodded. “I tend to agree with you.”

“So—the question is why? Why the elaborate hoax to make her appear to be dead? Why the charade carried out by both the Nazis and the Russians, including our lovable Major Krasnov? Why?”

“I’ll be damned if I know,” Hall said. “What the hell is so all-fired important about her anyway?”

“I don’t know,” Woody said soberly. “I honestly don’t know. I only know that we’d better find out.”

“And I suppose you already have a plan for doing just that,” Hall commented caustically.

“I do.”

“Let’s hear it,” Hall said.

Woody told him.

Hall sat staring at him. “You’re out of your gourd,” he said. “No way.”

“Okay, Mort,” Woody conceded, “I realize you can’t okay an operation as unorthodox as that.” He looked straight at his CO. “I want your permission to go over your head.”

Hall contemplated him. “Streeter?” he asked.

“I was thinking of Buter.”

Hall pursed his lips. “It’ll have to go through channels.”

“As long as it gets all the way to Buter.”

“What you propose is without precedent,” Hall said. “You realize that?”

“I do.”

“You won’t get to first base.”

“I can try.”

For a moment Hall sat in silence. It

was

a totally unique situation. It could be an important case. A helluva case. Perhaps it did warrant unique procedures. He sighed.

“I suggest you write up a report,” he said. “One hell of a good one. Buter will want to know details before he goes out on a limb with this one. Write it through channels. To me. I’ll walk it through. In person.” He looked at Woody. “And, Woody, if you

are

going ahead with this crazy scheme, write the damned report yesterday. You don’t have much time to screw around.”

I.

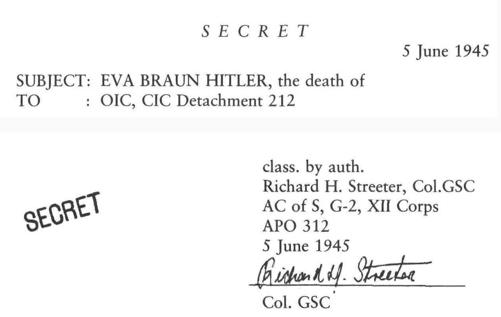

CASE CHRONOLOGY

On 28 April 1945 the capture of SS Sturmbannführer Franz Gotthelf was effected in Albersdorf, O-979623. During interrogation subject disclosed he was a dentist having worked with Brigadeführer Hugo Blaschke, personal dentist to Adolf Hitler. Among high-ranking Nazi patients of subject was

Eva Braun,

described by subject as Hitler’s mistress. Subject had worked on a dental bridge for said

Eva Braun.

Subject stated this bridge was never fitted, but remained in dental laboratory in Berlin when city fell to Russian forces.On 1 May 1945 SS Obersturmbannführer Leopold Krauss was interrogated in Weiden, O-869427. Subject stated he had been a Foreign Affairs Analyst in the Ministry of Propaganda attached to the Führer Bunker in Berlin. He stated he had fled Berlin 30 April 1945. He further stated that Adolf Hitler had married

Eva Braun,

29 April 1945, that both Adolf Hitler and

Eva Braun Hitler

had committed suicide, 30 April 1945 and their bodies burned in the garden of the Reich Chancellery. SS Obersturmbannführer Leopold Krauss was evacuated to AIC, 1 May 1945.On 2 May 1945 the Reich Chancellery and the Führer Bunker fell to Russian forces. The remains of Adolf Hitler and

Eva Braun Hitler

were found.On 6 May 1945, according to AIC records, SS Sturmbannführer Franz Gotthelf was turned over to Russian military authorities by AIC at request of Major Vasily Stepanovich Krasnov, Liaison Officer, XII Corps, to assist in identification of remains of Adolf Hitler.

On 8 May 1945 the Forensic-Medical Commission of the Soviet Army issued and disseminated internally an autopsy report covering the bodies found burned in the Reich Chancellery garden, 2 May 1945, by members of the Soviet Army Counter Intelligence SMERSH. A copy of this report was obtained by AC of S, G-2, XII Corps. The report contained 13 (thirteen) autopsy documents; 5 (five) adults; 6 (six) children and 2 (two) dogs. Document No. 12 covers the identification and autopsy report of Adolf Hitler. Document No. 13 covers the identification and autopsy report of

Eva Braun.According to Russian autopsy report positive identification of the bodies of Adolf Hitler and

Eva Braun

was made by use of dental records and interrogation of dental workers familiar with these records. The decisive item of identification in the case of

Eva Braun

was a dental bridge “of yellow metal” (gold) with artificial teeth attached. In part the autopsy report states: “Almost the entire top of the cranium and upper part of the frontal cranium are missing; they are burned. Only fragments of the burned and broken occipital and temporal bones are preserved as is the lower part of the left facial bones.” The bridge used to identify the body is reported to have connected the second right bicuspid and the third right molar. It is described as follows: “On the metal plate of the bridge the first and second artificial white molars are attached in front; their appearance is almost indistinguishable from natural teeth.” The report also states that: “On the right side no teeth were found, probably because of the burning.”This investigator, in an attempt to conduct a follow-up interrogation of dental assistant SS Sturmbannführer Franz Gotthelf (see: I-1) regarding his work on the crucial

Eva Braun

dental bridge, and unable to locate this subject at AIC, contacted Major Vasily Stepanovich Krasnov, Russian Liaison Officer, XII Corps. Major Krasnov, who had originally requested subject Gotthelf be turned over to Russian authorities, denied any knowledge of the matter and that he had made the initial request. It was the official Russian position that no such individual as SS Sturmbannführer Franz Gotthelf existed.On 3 June 1945 this investigator, on TDY with CIC, VII Corps, interrogated subjects Konrad Bock and his wife, Helga, in Halle P-822839. The Bocks stated that they had been active in travel expediting of high-ranking Nazi fugitives seeking to exfiltrate Germany via an escape route called the B-B Axis because it runs between the towns of Bremen in Germany and Bari in Italy. They further stated that two young people were provided with forged documents and travel orders on 1 May 1945, an SS officer named Lüttjohann and a young women who gave no name—the only woman processed by the Bocks. Subject Helga Bock stated that she believed this woman to be

Eva Braun.On 4 June 1945 this investigator interrogated Herbert Kotsch, a colonel in the German army, retired, and his wife Gertrud at Rübeland, P-843620. This couple had also worked for the B-B Axis escape route. They stated that Lüttjohann and the woman had been in hiding in Rübeland for about three weeks and had embarked on their exfiltration on 2 June 1945, proceeding to a route stop at Bebelgasse 49 in Eisenach, O-933924.

During a search of the place of concealment used by Lüttjohann and the woman by this investigator, a woman’s handkerchief, with the initials

EB,

was found.