Equilateral (5 page)

Authors: Ken Kalfus

Earth as seen from Mars, 1894, end of evening twilight

.

Earth at maximum elongation, June 17, 1894

.

Earth will leave it to Mars, an older planet whose civilization must be superior in technology, morals, and interplanetary manners, to frame a proper response to the Equilateral. Thayer speculates that its inhabitants will fire back a Flare of their own, or that some geometry-based heliographic system may be deployed, or that Mars will perform its own symbolic excavations. Earth will be obliged to respond in kind, with every device at its disposal.

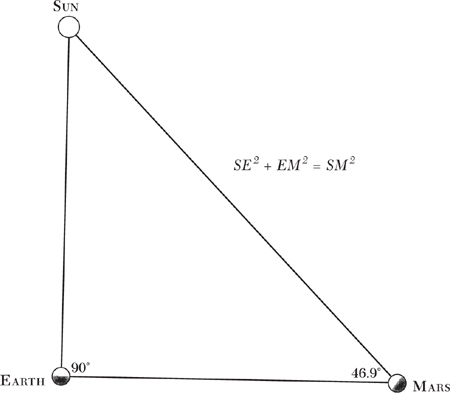

Thayer does not envision that his work will be completed June 17, 1894. More digging will have to be done, even if there is no immediate signal in return from Mars. In the ensuing two years, once the funds are raised, a new 266-mile line will be excavated in the Western Desert, from Point C to the midpoint of Side AB, which will be designated Point D. This bisection of the Equilateral, creating two Right Triangles, will be completed in time for the 1896 approach.

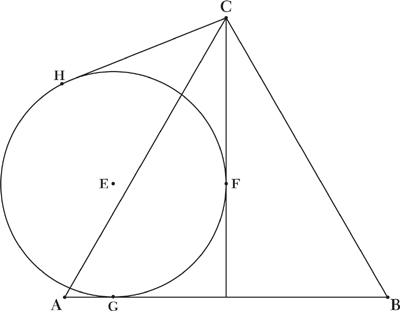

These excavations will prepare the desert ground for the next great Figure: a Circle tangent to Lines AD and CD at Points F and G, with its locus, Point E, near the Twenty-seventh Parallel, in time for maximum elongation in 1898. The Circle’s diameter will be equal to each of the Equilateral’s sides, casting a circumference of 968 miles whose arc will cross the frontier with Tripoli, still a Turkish dominion but increasingly within the shadow of Italian ambitions to secure a foothold in North Africa. Certain diplomatic maneuvers will have to be accomplished. Another tangent, from Point C to Point H, can be foreseen.

Further excavations.

By then Thayer will have begun constructing with Mars a common language based on the two planets’ shared knowledge of trigonometry, its words, its grammar, and its syntax flowing from the fixed relations between the length and positions of the Equilateral’s line segments, their angles of incidence, and the universal trigonometric concepts that can be derived from them. By constructing each side of the Equilateral 306.928 miles in length, precisely 1/73rd of the Earth’s circumference at the figure’s base, Thayer has brought a prime number, 73, into the conversation. Mars will recognize its significance: the ratio of Side AB to the Earth’s circumference will be prime in whatever counting system is favored by the fourth planet. By making AB parallel to the Earth’s equator and Line CD parallel to its axis of rotation, Thayer confirms man’s knowledge of his planet’s motion, which depends on other quantities that Mars could independently verify. These are the terms by which the solar system’s two species of intelligence will first begin to know each other.

Thayer hunches over his inclined drafting table, plotting the position of the planets when the 1900 and 1901 approach will occur. He requires few tools, for the complicated paths celestial objects appear to take across the curved firmament overhead—the pirouettes, the variable rising and setting times, the lunar and planetary phases, the sun’s long summer days and long winter absences—derive from simple clockwork motions within the three dimensions of transparent space, as perfect and predictable

and omnipotent as any geometry. While he steadies a compass around one of the foci of the Martian orbital ellipse, his pencil rolls off the table and drops soundlessly onto the Persian rug beneath the table.

“Bint!”

The girl appears beside him at once. She has probably been here all this time.

“Would you be so kind as to hand me the pencil?”

The girl doesn’t stir.

“The pencil, Bint?” Thayer says, and he recalls, as he must several times a day, that the girl speaks no English. Daoud Pasha offered to replace her with one who does, but Thayer has never accepted or rejected the proposal, not even making a gesture to indicate his indifference. Now, with his hands still on the compass, he dips his head toward the carpet and asks for the pencil again.

She doesn’t follow the movement of his head. He looks into her eyes and then down at the pencil, then back at the warm deep pools of her eyes and again at the pencil. When he returns to her face, she’s still looking directly into his. She offers the faintest, most respectful suggestion of amusement. Perhaps it’s there, perhaps it’s not.

Thayer laughs despite his frustration. He puts down the compass and goes to his knees. He’ll have to redraw the diagram from scratch.

“Pencil,” he says, holding it up to her face. “Pencil.”

Perhaps she has now learned the word for pencil. Or perhaps she believes she’s learned the word for raising an object before someone’s face, or the word for the color of the pencil, which is

in fact vermilion, or the word for recovering an object that has fallen, or the word for the flush that the exertion has brought to Thayer’s temples, or the word for laughing in frustration. She doesn’t repeat the word.

But she holds his stare. He studies her face with the idea that he will see it for the first time. He doesn’t succeed. Something veils her aspect, a cloud or a shadow.

Thayer’s health continues to improve, but Miss Keaton keeps her office near his quarters. Through one of the dragomen, she instructs Bint that he must take his quinine without fail.

Having returned from Point B, Ballard sourly notes the secretary’s protectiveness, which reminds him why he doesn’t like having ladies involved in engineering projects. Even when they don’t interfere directly in the endeavor, they project their fears and weaknesses onto their men. Thayer will benefit from an evening without Miss Keaton’s company.

Ballard suggests that he join him after dinner. A severely water-rationed hammam has been established on the far side of the encampment, hard by the diggers’ quarters, within a complex of mud-brick structures that tend to the laborers’ necessities, including their basest. Parallel facilities for white men lie adjacent and include a tea room that serves as the Club, some of whose furnishings Ballard has seen to himself: Anatolian kilims, water pipes, and a Bedouin saddle hung on the wall alongside an antique astrolabe. The engineer knows the astronomer usually enjoys an evening among men, whether they’re the world’s most distinguished astronomers or, at Point A, the Equilateral’s

engineers and overseers, some of whom have been under Ballard for decades and took heroic part in the construction of the great new barrage-dam at Aswan.

When they arrive at the tea room, Ballard and Thayer receive respectful, if wary, acknowledgments from the men, followed by a deep bow from the proprietor, Daoud Pasha. The Turk serves the new guests himself, attentive to information or any gesture or sign that he might turn to profit. Besides tending to the hammam and the tea room, Daoud Pasha has his hand in most of the Equilateral’s provisioning, under arrangements that remain obscure.

Ballard thinks the astronomer’s health has been compromised by too many nights in his tent with his astronomical charts and tables. His solicitations are sincerely tendered, but he also knows that his friend’s fatigue and pallor threaten the project’s completion as much as the marshes on Side AC do. The lavish expenditures of capital, the stupendous tonnage of machinery hauled to this wasteland, and the exhaustive outlay of physical effort dedicated to the excavations depend on immaterial theory and desire: Thayer’s. The Concession’s real investment lies primarily in the flesh-and-blood astronomer. Keeping him whole is the chief engineer’s responsibility, no less than it is Miss Keaton’s.

Thayer in turn likes Ballard but suspects that for him the Equilateral is no more than another civil engineering project and, preoccupied with the impediments, he fails to regard its grandeur. Ballard is an unreflective man. His decades in the desert haven’t left him with much of an affinity for quietude—he smokes, but not for him the contemplative drag on the hookah.

Now he leans over his tumbler of gin, about to make a point. He’s had too much to drink already. Thayer wonders whether, in a life under cloudless night skies, Ballard has ever thought about the stars and their secrets. As they led him across the burning sands of the Empty Quarter, did he listen to their murmurings? Did he dwell on their hidden and contradictory desires? Thayer is baffled that for modern men astronomy has lost its ancient status as the principal art, on which depend all other occupations, including engineering. Those who raised the pyramids knew the stars and kept in their good graces.

Yet Ballard has succeeded in driving the project forward, when the most renowned engineers of his age were intimidated by its ambitions. Sir John Hawkshaw declared that without a railroad it would be impossible to transport the necessary equipment into the Western Desert. István Türr predicted that windblown sands would obscure the figure long before it was completed. Ferdinand de Lesseps, Le Grand Français, the Builder of Suez, announced that the Equilateral could not be accomplished, neither for twice the price nor with five times the number of laborers. The single task of keeping nine hundred thousand men alive in the Western Desert, bringing them their every swallow of water and morsel of food, had daunted the greatest military men of the world’s greatest powers. Ballard has shown them that it can be done. Thayer recognizes that history will regard the Equilateral as much Ballard’s achievement as his own.

Now the engineer declares, “Sanford, I’ve heard rumors of war. It was a blunder to stop at the Atbara River, thank Whitehall, but reinforcements are on the way. Warwicks and the

Cameron Highlanders. Surely this year’s campaign will strike directly at Omdurman. The khalif will be ground into dust, don’t you think?”

“I suppose,” Thayer says vaguely. Fatigued by his illness, he’s drinking only tea tonight. “I haven’t seen the newspapers.”

“This isn’t in the newspapers,” Ballard says, further deepening the creases around his sun-damaged eyes. “This is confidential information, the troops have been seen disembarking in Alexandria, and it has some bearing on our enterprise. The troops are welcome, if the reports are true, for there’s not a single regiment between us and the Sudan. I don’t think you’d fancy having a thousand of those dervish boys showing up in camp tomorrow.”

“No, I wouldn’t,” Thayer concedes. “Not unless they come with spades.”

Ballard’s nod is grim. They had come with rifles to the Aswan Barrage—antiques, no match for the Maxims, but still, it was a nasty business, horses and men dead in the Nile, so bloated in the heat they could barely be distinguished from each other. Ballard has no Maxims here.

Δ

In the concluding decade of the nineteenth century, Egypt is a land where political power rests on semiviscous sands. The long-dying Ottoman Empire’s suzerainty has given way to British occupation. While the British consul general, Lord Cromer, exercises his nation’s control of Suez and the shipping lanes to India, just beyond Egypt’s borders the Sudan remains unsettled, under the sway of fanatics devoted to the Messiah they

call the Mahdi. For years the Mahdists have been making trouble, but now rifles have been brought into play and railroads and telegraphs have hastened the spread of religious infection. Europeans in Khartoum face brazen harassment. Raiders from the rebel capital, Omdurman, cross the Twenty-second Parallel without impediment. The savage beheading of General Charles Gordon and the destruction of his troops, sent to Khartoum to restore order, still aggrieves civilized sentiment nine years later.

In feverish, corrupt Cairo, the Khedive Abbas Hilmy II, technically an Ottoman viceroy, maintains a palace and an army under Lord Cromer’s supervision. He has granted the Mars Concession in exchange for certain material considerations and in the private belief that Egypt’s destiny enfolds the Equilateral. At dusk the military-trained son of Tewfik and the great-great-grandson of Mehmet Ali, the first khedive, steps from his palace chambers onto a marbled terrace and gazes upon the distant Platonic solids in Gizeh, their stones as soft as halvah in the guttering light. The strength and ambition of youth run in his blood on these melancholy evenings; he also senses, coursing through him, his people’s millennia, majestic and submissive, enigmatic and frequently catastrophic.