Enemy on the Euphrates (39 page)

Read Enemy on the Euphrates Online

Authors: Ian Rutledge

And so the antipathy between the head of the Civil Administration in Iraq and the army on the one hand, and between the former and the person who was, in effect, his intelligence chief on the other, continued to smoulder, and it wouldn’t be very long before a serious disagreement would develop within the army High Command in Iraq itself. All in all, it wasn’t a very propitious start to the campaign to defeat what would turn out to be a far tougher enemy than any of these individuals could have imagined.

General Haldane’s Indian Army

While the army objected to Wilson’s ‘interference’ in military matters on grounds of protocol, General Haldane could hardly have disputed the basic facts of Britain’s current military weakness in Iraq to which Wilson had drawn attention since he himself had noted many of the same weaknesses on his arrival there. Although Churchill had continued to press him for troop reductions – in April he had demanded that Haldane reduce the garrison of Iraq by 50 per cent by the next financial year – Haldane felt obliged to inform him that, for the time being, any reductions would have to be put on hold until the autumn and that in the meantime it might be necessary to bring some of his weakly manned units up to full strength.

On paper, Haldane’s army consisted of two divisions, the 17th commanded by Major General G.A.J. Leslie, and the 18th commanded by Major General T. Fraser, the former with its HQ at Baghdad, the latter, 240 miles to the north at Mosul. In addition, far to the south, there was an under-strength brigade-sized force commanded by Brigadier General H. E. C. B. Nepean composed of three Indian battalions, a cavalry regiment and some support troops scattered around the so-called ‘River Area’ most of which lay in the vilayet of Basra.

As was customary in the Indian Army, the infantry of each division was organised in three brigades, each containing one British and three Indian battalions. However, in May 1920, one brigade of the 17th Division, the 51st, had lost one of its British battalions – the 2nd Battalion York and Lancaster Regiment – which was one of the two

units Haldane had sent as reinforcements to Noperforce in north-west Persia after the Enzeli incident.

At full establishment, a British battalion in the period 1914–20 consisted of 1,007 men, of whom thirty were officers. Battalions were commanded by a lieutenant colonel with a major in second command and each of the four infantry companies of 227 men were commanded by a captain, or sometimes a major. In theory, an Indian battalion would have been organised on the same basis except that fourteen of the thirty officers would have been of Indian nationality.

1

There were also a variable number of ‘followers’ attached to each Indian unit. However, in reality, the strength of both British and Indian battalions varied considerably. In Iraq, in July 1920, in spite of remarks made previously by Wilson, the Indian battalions appear to have been reasonably well manned with an average strength of 846 men and officers; but the five British ones were seriously under-strength and only averaged 576 men and officers.

2

Excluding the 3,000 British and 23,000 Indian troops belonging to the Royal Army Service Corps, depot guards, medical services etc. tied up in non-combatant duties, at the beginning of July 1920 the remaining 9,000 British and 38,000 Indian troops under Haldane’s command were scattered over a vast area from the armistice line with Turkey to the Persian Gulf – a distance of roughly 600 miles – and from the Upper Euphrates to north-west Persia, a similar distance. Indeed, 3,500 British and 6,000 Indian troops constituting Noperforce were either 450 miles from Baghdad, confronting Bolshevik and Persian nationalist troops in the vicinity of Qasvin, or spread out along the hundreds of miles of mountain road reaching back from Qasvin through Hamadan, Khoramshah and Karind to the railhead at Quraitu in Iraqi Kurdistan. Other troops were resting at the Karind ‘hill station’, itself 150 miles from the Iraqi capital.

These distances ‘as the crow flies’ give no idea of the actual time required to travel from one point to another. For example, from Qasvin in northwest Persia to Baghdad required a march of not less than six weeks over difficult mountain roads. In Iraq, the movement of forces could easily be curtailed by a different set of problems: when the Tigris and Euphrates were at maximum flow – between April and May – roads could suddenly disappear under the flood waters of the two great rivers and in the winter heavy rains could turn the same unmetalled roads into a soup of alluvial mud. The availability of rail transport only improved matters slightly: for example, travelling by rail from Basra to Mosul could take a fortnight owing to inefficient rolling stock and indifferent railway personnel.

Indian cavalry on patrol,

c

.1918

In addition to the troops in Persia currently unavailable to Haldane, 1,700 men were sick and 1,600 in transit. This left Haldane with a mere 4,200 British and 30,000 Indian troops available to meet the outbreak of the insurgency in the Rumaytha region. Of these 26,600 were infantry, 2,900 cavalry and 4,700 gunners: among the infantry the vast majority – 89 per cent – were Indian and excepting two under-strength British cavalry regiments currently ‘resting’ at Karind in Persia, the cavalry were all Indian while Indians also made up the majority – 72 per cent – of the artillerymen.

The three infantry brigades of the 17th Division were strung out over a vast region from Kirkuk, HQ of the 52nd Brigade on the edge of Kurdish territory, to the Upper Euphrates where its 51st Brigade had

been dispatched to counter Arab raiders on the Syrian border, and then south as far as Hilla where the 34th Brigade was the only formation within striking distance of the rebel area.

The three brigades of the 18th Division were also spread out over an equally vast area up the length of the northern Tigris from Tikrit to Zakho in the far north, where the threat of an advance by Mustafa Kemal’s Turkish forces had to be contained, while at the same time Mosul and the reoccupied Tel ‘Afar had to be protected against the possibility of another raid north by Jamil Midfa‘i’s men out of Dayr az-Zawr.

Given that the vast majority of Haldane’s forces were Indian troops and were to bear the brunt of the fighting against the Iraqi insurgents, what sort of men were they? According to the commanding officer whom Haldane had recently replaced, General George MacMunn, they were predominantly men from the ‘martial races of India’. In 1911 this senior Indian Army officer had written a lavishly illustrated work,

The Indian Army

, published by that doyen of Edwardian illustrated books, A. & C. Black.

3

In it he expounded the currently widely accepted opinion that while the European was always ready for war, among ‘Asiatics’ only specific ‘races’ were capable of emulating the ‘white man’, the remainder having become enervated by long periods of exposure to warm, steamy, tropical climates, exacerbated by lengthy periods of peace during which any ‘martial’ spirit they may have once exhibited had become totally dissipated. As he put it, bluntly, in a later work, ‘In India we speak of the martial races as a thing apart and because the mass of the people have neither martial aptitude nor physical courage … the courage that we should talk of colloquially as “guts”.’

4

Moreover, in accordance with the predominant orientalist thinking there was a rural–urban dimension to the question: whereas the hardy native ‘yeoman’ working his own farm could make an excellent soldier, the educated or semi-educated townsman had become totally unfit for combat. MacMunn gives as an example a favourite target – ‘the people of Bengal … those with the most-cultivated brain, the trading classes, the artisan classes …’ who, as far as military ardour was concerned, were ‘hopeless poltroons’, contrasting them with ‘the great, merry, powerful Kashmiri’; although MacMunn also warns his reader that physical appearance does not always have anything to with the matter, since ‘some of the most manly-looking people in India are, in this respect, the most despicable.’

5

Therefore, ‘In India … certain classes alone do the soldiering and kindred service. These are roughly, in central and northern India, the yeoman peasant, the grazier and the landowner. Very good classes, too, as everyone can see.’

6

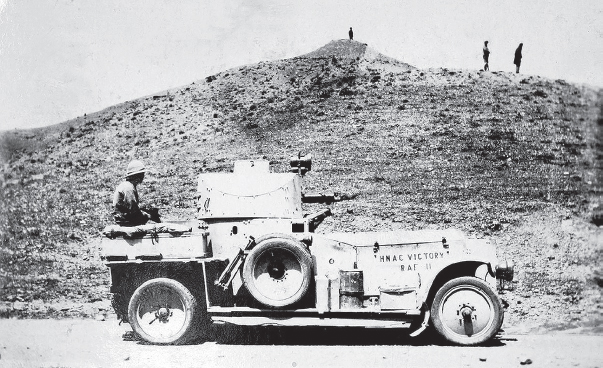

A Rolls-Royce armoured car of the type used in Iraq in the 1920s

As time went on, British officers in India became increasingly obsessed by the arcane distinctions of race and caste whereby they distinguished ‘martial’ communities from ‘non-martial’ and one group of ‘martial’ troops from another, to the extent that certain communities were held to have developed specific ‘racial’ characteristics which dictated which particular military function they should perform. For example, the Hazaras (a community of Shi‘i Afghans, some of whom had migrated to India) were held to be especially suited to the role of pioneer/sapper – soldiers who could fight as infantry but whose principal role was the construction of roads, bridges and siege works. Thus, we find that the support troops of the 18th Division in Iraq in July 1920 included the 106th (Hazara) Pioneers.

More commonly, segregation by particular ‘martial race’ was carried

out at the company, rather than the battalion, level. For example, the 86th (Carnatic) Infantry Regiment – in July 1920 just arrived in Iraq from India as a relief unit – would have had four companies of Madrasi Muslims, two companies of Tamils and two companies of Pariahs. Yet others, like the 114th (Mahrattas) Infantry Regiment, whose men were the first to see action against the Iraqi insurgents, might have a majority of men drawn from one particular community but depending on the circumstances, a minority made up of other groups – in this case six companies of Mahratta Brahmans and two companies made up of other communities, as circumstances dictated. The same principle ruled in the Indian cavalry. For example, in the Scinde Horse, who had arrived in Iraq in March 1920, ‘A’ squadron was composed of Sikhs, ‘B’ squadron of Pathans and ‘C’ squadron of Derejats.

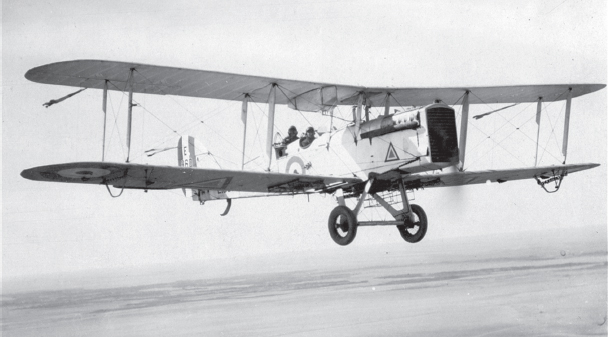

The more modern DH9A which largely replaced the elderly RE8 towards the end of the uprising

In reality, many of the fine distinctions and defining characteristics of race, caste, class and region were largely in the minds of the British officers who constructed them; but over time, clan or class loyalty among the Indian troops became self-reinforcing as men returned from military service to their communities with their turbans tied or beards trimmed in the regulation manner adopted by their regiments and retained these fashions in their civil dress. Then, they and their families retained these

distinctions to emphasise their military connections. Subsequently, later generations, both Indian and British, would come to see these fashions as deeply rooted caste distinctions, sanctified by tradition.

7

Many of the Indian soldiers who were now facing the Arab insurgents had already served in Iraq during the Great War: take Jemadar (Second Lieutenant) Har Chand of the 99th (Deccan) Infantry Regiment, for example.

Har Chand had joined the Indian Army on 8 June 1907 as an ordinary sepoy (infantryman).

8

By religion, he was a Sikh, although in all probability he came from a town or village on the central Indian plateau near Hyderabad which had a large Muslim population – possibly Secunderabad, where the 99th Deccan had its headquarters. Between 15 August 1915 and 15 May 1916, Har Chand fought in Iraq, although it seems likely that this was after being drafted from the 99th to some other unit. On his return to India he rejoined the 99th and from 3 to 23 March 1917 he took part in operations on the North-West Frontier, fighting rebel Mahsud tribesmen in southern Waziristan. In early 1917 the 99th Deccan were at last called to duty overseas, arriving in Iraq on 8 April. The regiment was soon attached to the Euphrates Defence Force, which was assigned lines-of-communications duties along the river. During the course of these, Har Chand was commissioned jemadar on 20 February 1918 and as such, he would have commanded a half-company of two sections, each under a havildar (sergeant). Based at Nasiriyya, the regiment was not at the front fighting the Turks but it took part in two major punitive operations against hostile Arabs around Rumaytha, during which the unit suffered nineteen casualties.