Enemy on the Euphrates (14 page)

Read Enemy on the Euphrates Online

Authors: Ian Rutledge

First, Sykes informs Cox that ‘the following is a resume of situation from the Arab point of view as described to me by Faruqi here’. He goes on to state that ‘the Arab Committee here [i.e. in Cairo] and the Sharif are in accord’, and also in agreement with ‘members among Baghdad Army officers’. This ‘Arab Committee’ planned to form an independent state or confederation. However, Sykes then adds the following observation, suggesting that their objective of full independence is somewhat less than absolute.

They are obliged for political reasons to demand absolute independence. That is why members of Committee do not open-up on subject. If they accepted principle of foreign control they would lose the support of the Syrians, however in fact this does not amount to much.

1

Sykes then lists the territories which would form the new Arab state: ‘Vilayet

s

of Damascus, Beirut, Aleppo, Mosul, Baghdad and sanjaks of Urfa, Dayr az-Zawr, Jerusalem.’ The form of government will be

‘Decentralised Turkish Government under a Parliament sitting in Damascus’. But then, echoing his earlier observation, he adds that the independence of the new state will be

qualified by agreements made with France and Great Britain … France to have a monopoly of all enterprise and special educational facilities in region west of the Euphrates as far as Dayr az-Zawr and in Palestine. No Europeans but Frenchmen to be employed by Arab state in that area, but Arab state not to be obliged to employ European Advisors unless it chooses. Great Britain to have same rights in … Mesopotamia. Basra town and lands south to border with Kuwait and to Fao to be British absolutely. Lands to the north of the line Alexandretta, Aintab, Urfa to be French absolutely.

Sykes then turns specifically to Iraq, Sir Percy Cox’s current responsibility.

Shi‘i problem and Karbela’ question would to my mind make our cooperation in government in Baghdad and Basra province inevitable. Arabs have agreed they could not take over this region for present and further point out that revenues and development of these provinces will be essential to their economic and financial stability and that these could only be got with our assistance.

He ends with these comforting words:

If we have a permanent monopoly of enterprise and of European assistance, military and civil, in Mosul, Baghdad and Basra province, and we administer Baghdad and Basra province for the duration of the war, I think that we need not fear for the future. If Pan-Arabism succeeds, and if it does not, we have given nothing away.

2

The salient points Sir Percy was apparently intended to draw from this confusing telegram were as follows.

1) There exists in Cairo an ‘Arab Committee’ of considerable importance.

2) The political position of this ‘Committee’ is identical to that of the Sharif of Mecca with whom they are in communication.

3) the Committee (and by inference, the Sharif of Mecca) are, in reality, willing to accept something less than full independence.

4) They are only demanding full independence ‘for political reasons’ in order to avoid conflict with ‘the Syrians’ and might otherwise even ‘accept the principle of foreign control’ (whatever that means).

5) These ‘Syrians’ (who, by implication, are more extreme nationalists) are nevertheless less influential than the ‘Baghdad officers’ and the Sharif’s supporters.

6) The form of government to be adopted in the new Arab state is very similar to the model recommended in the De Bunsen report, i.e. ‘Decentralised Turkish Government’.

7) They have the option to accept foreign advisors and if they do (and there is the implication that they will) the Arab movement is equally comfortable with a strong French influence in the western and northwestern part of its domain as it is with a strong British influence in the eastern and south-eastern part.

8) The Arab movement is willing to concede the lower half of the vilayet of Basra including the city of Basra itself to be ‘British absolutely’.

The only problem Sir Percy Cox would have encountered in inferring these conclusions is that, as far as we are able to understand from the available historical evidence, none of it was actually true. In fact, Faruqi was a bit of a fraudster.

By the time Faruqi met with Sykes he had already been living in Cairo in close proximity to leading personages in the military and intelligence community for nearly three months. He seems to have been sharp and intelligent and during this time the numerous interrogations and interviews in which he had been involved would have given him considerable insight into the strategic and political preoccupations of his interrogators. It is also possible that, as a competent linguist (he already spoke Turkish and French), he had considerably improved his knowledge of English. So, having apparently decided that his comfortable and, to an increasing degree, respected status was very much dependent on convincing the British that he was able to ‘deliver’ to them an Arab movement consistent with their strategic and political

preoccupations, he gave them what they – rather than the Sharif of Mecca – wanted.

The lies began almost immediately Faruqi arrived in Cairo. He knew very well that only a tiny proportion of Ottoman army officers belonged to al-‘Ahd: his figure of 90 per cent was pure fabrication. He also knew that his claim that al-‘Ahd included a ‘part of the Kurdish officers’ was misleading to say the least – there were perhaps no more than a handful of members who were of Kurdish origin. Faruqi certainly did

not

unite the al-Fatat and al-‘Ahd movements: that was achieved by a senior Iraqi officer, Yasin al-Hashimi. Al-‘Ahd had never carried out propaganda among the Arab troops: on the contrary, its members had tried as much as possible to conceal their activities. There had been no approach to al-‘Ahd by the Turks or Germans offering an alliance, as Faruqi informed Shuqayr (the Germans had never even heard of al-‘Ahd). And Faruqi had not been authorised by al-‘Ahd, the Sharif or any other part of the ‘Arab movement’ to ‘receive’ the British response to their demands.

3

Furthermore, as regards the ‘information’ which Sykes obtained from Faruqi during their interview, there was no ‘Arab Committee’ in Cairo. Neither the (non-existent) committee nor Faruqi himself were in communication with Sharif Husayn – in fact it was to be a further month before Faruqi contacted Husayn and informed him of his existence. And with respect to French influence, although Husayn was later to offer some flexibility over French interests in the coastal region of Syria at Britain’s request, at this point in time both he and the majority of al-‘Ahd members were strongly opposed to

any

French involvement in a new Arab state, in spite of what Faruqi may have said to Sykes.

4

So, comforted by the apparent ‘reasonableness’ of the Arab movement, as relayed to him by Faruqi, Sykes returned to England where, almost immediately, he was thrust into negotiations with M. Charles François Georges-Picot, French counsellor in London and former French consul general in Beirut, to try to harmonise Anglo-French interests in ‘Turkey-in-Asia’. For nine months the French had been intermittently raising this question with Britain. So during the first week of January 1916, Sykes and Picot hammered out a draft agreement. Finally, as a result of an exchange

of letters between Sir Edward Grey, the French foreign minister, Paul Cambon, and Serge Sasanov, the Russian minister of foreign affairs, a secret agreement was reached among the three Great Powers defining their respective claims on Turkey’s Asian provinces. Its terms were embodied in a letter from Grey to Cambon dated 16 May 1916, and in due course it was to become known as the ‘Sykes–Picot Agreement’.

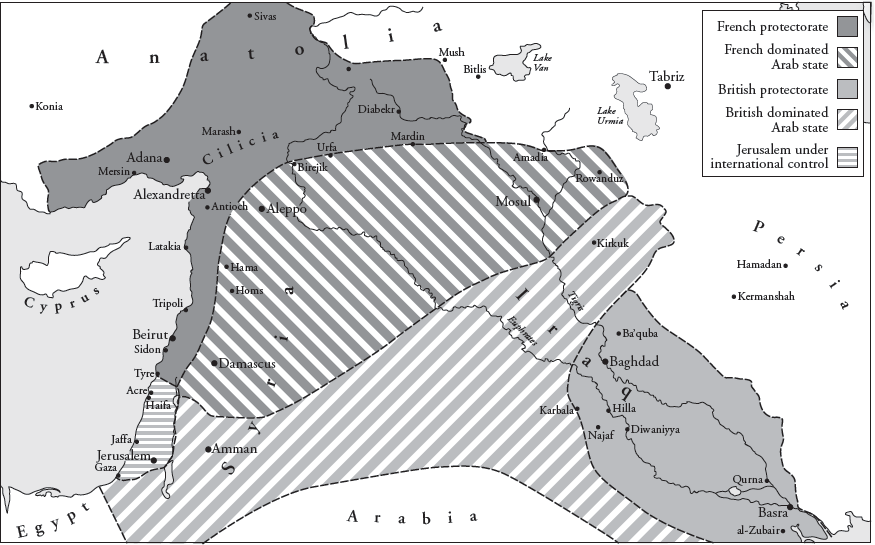

The essence of the agreement was that the Ottoman Middle East, excepting the Arabian peninsula and Palestine (which was to be ‘internationalised’) was to be split in two, roughly on a north-east–south-west axis which would run from a point just north-east of Kirkuk on the border with Persia, across northern Iraq and the Syrian desert, through the present-day occupied Palestinian West Bank and ending on the Mediterranean coast at the Gaza Strip. The central, inland core of each region, designated Area ‘A’ and Area ‘B’, respectively, would be a region in which France and Britain agreed ‘to recognise and protect an Independent Arab State or Confederation of States … under the suzerainty of an Arab Chief’. In Area ‘A’ France would have ‘a right of priority in enterprises and local loans’, and Britain would have the same right in Area ‘B’. Only France, in Area ‘A’, and Britain, in Area ‘B’, should supply foreign advisors or officials, if these were requested by the ‘Arab State’. However, on either side of this region there would also be a ‘Blue’ area and a ‘Red’ area, the former including the Syrian littoral and the southern part of Asia Minor, the latter including the vilayets of Baghdad and Basra. In these areas Britain and France were at liberty ‘to establish such direct or indirect administration or control as they may deem fit to establish after agreement with the Arab State or Confederation of States’. In effect these ‘Blue’ and ‘Red’ areas would be French and British protectorates. In addition, Alexandretta, on the Syrian coast, and Haifa, on the coast of Palestine, would be free ports with respect to Britain and France, respectively, and Britain would have the right to build, administer, and be the sole owner of a railway connecting Haifa with the ‘Red’ area.

5

There was just one matter which may have caused Sykes some unease: in this carve-up Mosul and the surrounding area would form part of the

French-aligned ‘A’ zone, albeit within a semi-autonomous Arab state. Sykes was well aware of the potential oil wealth which lay in this region, but it seems that broader geostrategic concerns prevailed at this particular juncture. Even in a wartime alliance with the tsar’s empire, British policy makers were still playing ‘the Great Game’: it was apparently thought advantageous that, once the war was won, Britain would have a French-controlled buffer zone between its interests in Basra and Baghdad and the Russian Caucasus. Mosul would have to be part of that ‘buffer’.

Nevertheless, in all other respects Sykes had done it – or so he believed. He had squared the circle. He had made an agreement with Picot which satisfied both Britain and France while at the same time believing that he was broadly respecting the wishes of Sharif Husayn and the ‘Arab movement’ as related to him by their ‘representative’ Lieutenant Faruqi.

6

Needless to say, neither Sharif Husayn nor his sons had the slightest idea that their objectives had been so seriously misconstrued by the Power to whom they were about to commit their forces and in whose service they were to risk all.

THE DIVISION OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE’S EASTERN POSSESSIONS ACCORDING TO THE SYKES-PICOT AGREEMENT 1916

Two British Defeats but a New Ally

The urgency of inducing Sharif Husayn and his sons to enter the war – even if they provided only a minor distraction to the Turks and a small symbol of Allied–Muslim cooperation to the world at large – was now becoming acute. The war with the Ottomans was not going well – and not just at Gallipoli.

On 21 October 1915 Maurice Hankey, now secretary of the newly established War Council, was lunching with the foreign secretary, Grey, at Churchill’s London house, which Grey was currently renting. Later that day a special interdepartmental committee meeting had been arranged specifically to discuss whether the Mesopotamian Expeditionary Force, which had recently advanced up the Tigris and captured the small town of Kut al-‘Amara, should continue the advance and take that ‘glittering prize’, Baghdad. The expeditionary force’s commander, General Nixon, was reported to be strongly in favour. Grey asked Hankey what were his views on the matter. Hankey told Grey that the Mesopotamian Expeditionary Force should certainly ‘push on to Baghdad without delay’, and he added that on arrival, the army should ‘issue a proclamation that we had occupied the city temporarily and for military reasons only and that we were favourably disposed towards the formation of an Arab Empire independent of Ottoman rule, to which Baghdad might be handed over’.

1

Grey agreed, and in the afternoon the special committee, under the impression that the forces at the disposal of General Nixon were greater than they actually were, approved the advance on Baghdad, the decision

to authorise the advance being telegrammed to Nixon on the 24th. Nixon was already brimming with optimism. In spite of the fact that his field commander, Townshend, had already complained that his commander-in-chief ‘does not seem to realise the weakness and danger of his [Townshend’s] line of communication … 380 miles from the sea’, Nixon had already ordered some of his troops to move up from Kut to positions sixty miles upstream. Far away in London the cabinet looked forward to a sparkling victory which would offset the dismal news from Gallipoli and the Western Front.

On 2 November 1915 the prime minister, Asquith, speaking in the House of Commons, gushed with enthusiasm: ‘General Nixon’s force is now within measurable distance of Baghdad. I do not think that in the whole war there has been a series of operations more carefully contrived, more brilliantly conducted, and with a better prospect of final success.’

2