Enduring (64 page)

Authors: Donald Harington

The Questcamera will, however, fall in love with her cats, stalking them while they are stalking, pouncing when they pounce, beating them in staring matches, and affectionately bumping heads with them. Boastfully, the machine will chase birds the cats cannot reach, but as if to get even, the cats will snatch at fish in the creek, and when the Questcamera tries to do this, it will get all wet and Brian will have to fix it.

Every night the Questcamera will follow Latha to bed and remain alert until she dozes off. It will be curious about what books she is reading, and will read over her shoulder. But before putting out the light, she will need to visit the bathroom and will turn off the Questcamera while she sits patiently and recites to herself:

Tinkle, tinkle, little pee

.

How I wonder if I be

.

If I be enough to keep

,

I must pee before I sleep

.

Fortunately for posterity, although the Questcamera’s eye will be shut, its ear will still be open and it will catch and remember this ditty, Latha’s sole contribution to the world of poetry.

Before the quilters will have given up their needles and returned to more manly pursuits, each of them will select and supervise the piecing of his own personal burial quilt, and Brian will take back with him to St. Louis a lovely quilt in the so-called crazy quilt pattern, which, he will be heard to maintain, is symbolic not only of his life but also of this book. Possibly he will not ever be buried in it, because it will not be too many more years before medical science, with some help from Vernon Ingledew, will eradicate death. Even before the total abolition of death, or rather the beginning of the universal program of voluntary leave-taking, medical science, again with some help from Vernon Ingledew and his co-conspirator Day Whittacker, will have discovered and perfected the age-reversal process, whereby everyone, if they will so choose, can grow younger instead of older. Latha will not so choose. Records will no longer be kept, but the Guinness Book will have gone out of print for years, and no one will know if Latha is the oldest woman on earth.

But as she will have said, she will outlive her creator, who, like Hank Ingledew and George Dinsmore and countless others, will breathe his last at the age of eighty-six. That last breath will be with difficulty, owing to pneumonia, which will have plagued him periodically for years and which took away his mentor, William Styron, in 2006. He will use that last breath to whisper into the ear of his beloved wife Kim his parting sentiments and also a reminder that Latha and the quilters will have already determined that the remainder of the

Enduring

book can be readily composed by the reader.

Some of those readers will have already turned out the light and tried to sleep. Others will first, before turning out the light, want to visit their bathrooms for the recitation of Latha’s ditty. Still others will insist that they want to remain awake long enough to read the story of a “visit” that Latha will receive, via the high technology senseophone, which enables us to feel literally in the presence of the caller. The woman will not be age-reversed and will appear to be as old as Latha herself. She will declare that her name is Rachel Rafferty, and that she had known Latha very well during her confinement to the Arkansas Lunatic Asylum.

“But,” Latha will protest, all of it coming back to her, “you aren’t

real

.”

“Who is?” Rachel will say. “But I must admit that this new senseophone my triple-great grandson gave me for Christmas makes you so real I could reach right out and touch you.”

“But,” Latha will say again. “But Dr. Kaplan convinced me you were entirely in my imagination.”

“Kaplan!” Rachel will exclaim as if it were a dirty word. “That asshole wouldn’t have known I was a figment if I’d have put out for him. Kaplan and his phobias! There ought to be a word for a phobia of making someone happy.”

Latha will reach out to lay her hand on Rachel’s arm but will discover, as all of us will have at one time or another when using the senseophone, that it is only air. Still, the woman will be speaking so clearly, and it will have been so long since Latha last experienced any sort of hallucination, that she will begin to believe that the woman really is Rachel, who was her dearest friend at the asylum and who kept her from sooner going over the brink.

“Where are you calling from?” Latha will ask. The woman will appear to have a very long body, and Latha will recall that she had been a star basketball player who had got into serious trouble for fondling her minister during a baptism.

“I’m in New Orleans,” the woman will say. “Where on earth are you? I’ve been trying for years to find you.”

“I’m in a place called Stay More, Arkansas,” Latha will tell her, “which used to be my hometown, if you remember, but isn’t a town any more, just a place.”

“Are you well and happy?” Rachel will ask.

“Oh yes, I have no complaints,” Latha will declare, “except that they waited so long to invent a cure for death, and so many people I loved have died off.”

“Same here,” Rachel will say. “But now we’ve got each other, so let’s make the most of it.”

They will make the most of that call. For hours. They will reminisce about what a terrible place the asylum was, although Nurse Richter was a nice person until she ran away with Dr. Silverstein, and Betty Betty was a lot of fun. They will tell each other most of what has happened to them, beginning with how they got out of the asylum and everything since. From the distance of all these years, even the campus of the asylum will seem idyllic, with that pond and all those flowers. Latha will tell her to be sure and order a copy of a book called

Enduring

, because Rachel is in it. “I’ve known the guy who wrote it all of his life, and in fact he was buried here at the Stay More cemetery. You must come up and visit sometime.”

“I’ll do that when they invent teleportation,” Rachel says.

“At this rate, it won’t be long,” Latha says, and both women will laugh.

But the book will not end with the sound of their laughter.

It will not end with Latha going to bed later that night and dreaming of Rachel.

It will not end with somebody walking off into the sunset, or of an opened door about to close.

It will not end with an automobile driving off, or a train whistle blowing as the train pulls out (indeed, all surface travel will have ended years before).

It will not end with the sound of the spring on a screen door stretching and twanging.

It will not end with an invitation to stay more. It will not even end with an essay on how Latha will have always known the meaning of the town’s name and will have heeded it, and will still be heeding it.

It will not end with a goodbye, or a farewell or a godspeed or a catch you later. It will not end with any sort of valedictory.

It will not end.

About the Author

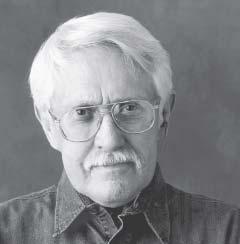

Donald Harington

A

lthough he was born and raised in Little Rock, Donald Harington spent nearly all of his early summers in the Ozark mountain hamlet of Drakes Creek, his mother’s hometown, where his grandparents operated the general store and post office. There, before he lost his hearing to meningitis at the age of twelve, he listened carefully to the vanishing Ozark folk language and the old tales told by storytellers.

His academic career is in art and art history and he has taught art history at a variety of colleges, including his alma mater, the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, where he has been lecturing for twenty-one years.

His first novel,

The Cherry Pit

, was published by Random House in 1965, and since then he has published fourteen other novels, most of them set in the Ozark hamlet of his own creation, Stay More, based loosely upon Drakes Creek. He has also written books about artists.

He won the Robert Penn Warren Award in 2003, the Porter Prize in 1987, the Heasley Prize at Lyon College in 1998, was inducted into the Arkansas Writers’ Hall of Fame in 1999 and that same year won the Arkansas Fiction Award of the Arkansas Library Association. In 2006, he was awarded the inaugural

Oxford American

award for Lifetime Achievement in Literature. He has been called “an undiscovered continent” (Fred Chappell) and “America’s Greatest Unknown Novelist” (Entertainment Weekly).

Table of Contents