Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber (12 page)

Read Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber Online

Authors: Geoffrey Block

Magnolia, a bystander in the first section and half of the second, has now dominated all but eight measures since she first pointed out to Ravenal that they are only pretending, after all. Most significantly, Magnolia introduces the return of the central “Make Believe” melody more intensely than Ravenal’s opening gambit, and to match this intensity the music escalates a half-step higher (E major) from the original tonic D. When Ravenal joins her on the words “others find peace of mind in pretending,” it is by now unequivocally clear that Ravenal and Magnolia are not like these others. Their love is real.

major) from the original tonic D. When Ravenal joins her on the words “others find peace of mind in pretending,” it is by now unequivocally clear that Ravenal and Magnolia are not like these others. Their love is real.

The distribution between Magnolia and Ravenal during this return of the main tune underwent several changes between the tryouts and the New York premiere, and there remains some lingering ambiguity about who should sing what after the first two lines (invariably given to Magnolia). For example, according to the libretto typescript in the Library of Congress’s Jerome Kern Collection (see “Manuscript Sources” no. 1 in the online website), Kern and Hammerstein had once indicated that Magnolia alone should sing the next lines (“Others find peace of mind in pretending—/ Couldn’t you, / Couldn’t I? / Couldn’t we?”) before they conclude their duet. The evolution of the final line is especially intricate.

Hammerstein remained unsatisfied by his decision to have both principals sing the last line (“For, to tell the truth,—I do”). Was Magnolia ready to admit the truth of her love to Ravenal? In a penciled change Hammerstein has Ravenal sing the “I do” without Magnolia. In the New York Public Library libretto typescript (see “Manuscript Sources” no. 2 in the online website) the entire last line is given to Ravenal alone but placed in brackets. In the New York production libretto published with the McGlinn recording (no. 3) Ravenal sings the final line (without brackets), and this version is

preserved in the published London libretto of 1934 (no. 4), the 1936 screenplay (no. 5), and the 1946 New York revival (no. 6).

61

Further contributing to the ambiguity and confusion is the lack of correspondence between these text versions and the piano-vocal drafts and published scores, none of which specifies that Ravenal profess his love alone until the Welk score (which corresponds to the 1946 production), where Magnolia’s “For, to tell the truth,—I do” is placed in brackets.

62

Perhaps most revelatory about these manuscripts are Kern and Hammerstein’s gradual realization that this portion of the scene needed to focus more exclusively on Ravenal and Magnolia. The New York Public Library and Library of Congress typescripts, for example, present two versions of a conversation between Ellie and Frank that would be discarded by the December premiere.

63

Hammerstein eventually concluded that this exchange slowed down the action and distracted audiences from their focus on Ravenal.

64

A second interruption, also eventually discarded, occurred after the B section of Ravenal’s song “Where’s the Mate for Me?” (based on Magnolia’s piano theme,

Example 2.4

). Both the Library of Congress and New York Public Library typescripts present some dialogue and stage action during the twenty-six measures of underscoring that have survived in Draft 2: Parthy’s theme (

Example 2.3

), Cap’n Andy’s theme minus its six opening measures (

Example 2.2c

), and Ravenal’s theme (

Example 2.5

).

65

Moments later Parthy intrudes once again, shouting “Nola!,” and Hammerstein provides the following comment: “Magnolia looks down on this splendid fellow, Ravenal. Her maidenly heart flutters. She really should go in and answer mother—but she stays.”

66

Like the brief dialogue between Ellie and Frank that intrudes on this moment in the 1936 film, the appearance of Parthy here and after the B section of “Where’s the Mate for Me?” interrupts the focus on the soonto-be-lovers. Parthy, while always unwelcome, is also unnecessary during this portion of the scene, particularly since she had made a prominent exit shortly before we met Ravenal. Wisely, Kern and Hammerstein in 1927 allowed Parthy’s music to prompt Magnolia to tell Ravenal she “must go now” and avoided the reality of Parthy’s intrusion on the young couple’s private moment before “Make Believe.”

67

After

Show Boat

Kern and Hammerstein would collaborate on three of the composer’s remaining five Broadway shows, two with respectable runs,

Sweet Adeline

(1929) and

Music in the Air

(1932), and a disappointing

Very Warm for May

(1939). Despite their considerable merits, none of these shows have entered the repertory (although

Music in the Air

was chosen for New York City Center’s

Encores! Great American Musicals in Concert

in the 2008–09

season). Less than a year after

Show Boat

Hammerstein collaborated with Romberg on

The New Moon

, a show that went on for an impressive 509 performances. Then, despite the success of individual songs, including “All the Things You Are” from his final collaboration with Kern, Hammerstein’s series of unwise choices (both in dramatic material and collaborators) and hurried work resulted in eleven years of Broadway failures before he rose from the ashes with

Oklahoma!

Similarly, Hammerstein’s Hollywood years in the 1930s and early 1940s yielded no original musical films of lasting acclaim, although here, too, a considerable number of songs with Hammerstein lyrics have become standards.

68

Hammerstein also adapted the screenplay for the penultimate Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers film,

The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle

(1939).

69

In the next decade Hammerstein began his historic collaboration with Rodgers, and by the time

Show Boat

was revived in 1946, they had already written two of their five major hit musicals,

Oklahoma!

and

Carousel

(the latter the subject of

chapter 9

).

70

In addition to his subsequent work with Hammerstein, Kern created two successful musicals with Harbach, the unfortunately overlooked

The Cat and the Fiddle

(1931) and

Roberta

(1933), the latter best known in its greatly altered 1935 film version. In fact, most of Kern’s career after

Show Boat

was occupied with the creation of twenty-two full or partial film scores—thirteen original and nine adapted from Broadway—including several with lyrics by Hammerstein and the Astaire and Rogers classic

Swing Time

(1936), with lyrics by Dorothy Fields. Unfortunately, Kern never had the opportunity even to begin a new musical in the Rodgers and Hammerstein era, since he died shortly after Rodgers, who was producing a musical based on the life of Annie Oakley, had asked him to write the music.

71

Kern and Hammerstein’s inability to produce another

Show Boat

in the 1930s enhances the significance of their earlier achievement. Although its ending did not embrace Ferber’s darker version,

Show Boat

, “the first truly, totally American operetta” had dared to present an American epic with a credible story, three-dimensional characters, a convincing use of American vernacular appropriate to the changing world (including the African-Americanization of culture) from the late 1880s to 1927, and a sensitive portrayal of race relations that ranged from the plight of the black underclass to miscegenation.

72

As the first Broadway musical to keep rolling along in the repertory from its time to ours, while at the same time enjoying the critical respect of musical-theater historians for more than seventy years,

Show Boat

, the musical “that demanded a new maturity from musical theatre and from its audience,”

73

has long since earned its coveted historical position as the foundation of the modern American musical.

ANYTHING GOES

Songs Ten, Book Three

B

efore the curtain rose on the 1987 revival of

Anything Goes

at Lincoln Center’s Vivian Beaumont Theater, audiences heard the strains of Cole Porter’s own rendition of the title song recorded in 1934. At the conclusion of this critically well-received and popularly successful show a large silkscreen photograph of Porter (1891–1964) appeared behind a scrim to cast a literal as well as metaphoric shadow over the cast. More than fifty years after its premiere the message was clear: the real star of

Anything Goes

was its composer-lyricist, the creator of such timeless song classics as “I Get a Kick Out of You,” “You’re the Top,” “Blow, Gabriel, Blow,” “All Through the Night,” “Easy to Love,” “Friendship,” “It’s De-Lovely,” and the title song. Readers familiar with

Anything Goes

from various amateur and semi-professional productions over the past thirty years may scarcely notice that the last three songs named were taken from other Porter shows.

Anything Goes

, after the Gershwins’ Pulitzer Prize–winning

Of Thee I Sing

the longest running book musical of the 1930s and almost certainly the most frequently revived musical of its time (in one form or another), was Porter’s first major hit. Otherwise virtually forgotten, each of Porter’s five musicals preceding

Anything Goes

introduced at least one song that would rank a ten in almost anyone’s book: “What Is This Thing Called Love?” in

Wake Up and Dream

(1929), “You Do Something to Me” in

Fifty Million Frenchmen

(1929), “Love for Sale” in

The New Yorkers

(1930), and “Night and Day” in

Gay Divorce

(1932). The Porter shows that debuted in the years between

Anything Goes

and

Kiss Me, Kate

(1948) are similarly remembered mainly because they contain one or more hit songs.

Anything Goes

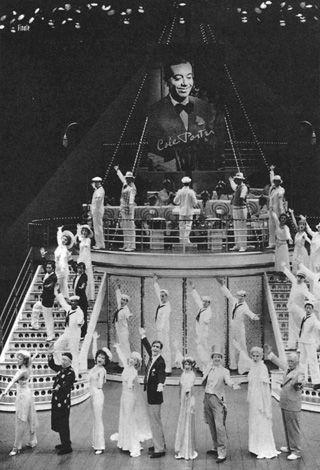

, act II, finale (1987). Photograph: Brigitte Lacombe.

In the unlikely Midwestern town of Peru, Indiana, Porter’s mother, appropriately named Kate, arranged to have Cole’s first song published at her own expense in 1902 (he was eleven at the time). Three years later Porter entered the exclusive Worcester Academy in Massachusetts. Upon his graduation from Yale in 1913, where he had delighted his fellow students with fraternity shows and football songs, Porter endured an unhappy year at Harvard Law School. Against his grandfather’s wishes and in spite of financial threats, Porter enrolled in Harvard’s music department for the 1914–1915 academic year. In 1917 he furthered his musical training with private studies in New

York City with Pietro Yon, the musical director and organist at Saint Patrick’s Cathedral; in 1919–1920 the future Broadway composer continued his studies in composition, counterpoint, harmony, and orchestration with Vincent D’Indy at the Schola Cantorum in Paris.

Although his first success,

Paris

, would not arrive for another twelve years, Porter had already produced a musical on Broadway,

See America First

(1916), before Gershwin or Rodgers had begun their Broadway careers and only one year after Kern had inaugurated his series of distinctive musicals at the Princess Theatre. The years between the failure of his Broadway debut after fifteen performances (inspiring the famous quip from

Variety

, “

See America First

last!”) and the success of Irene Bordoni’s singing “Let’s Do It” in

Paris

were largely dormant ones for Porter. In fact, the sum total of his Broadway work other than

See America First

was one song interpolation for Kern’s

Miss Information

in 1915 and approximately ten songs each in

Hitchy-Koo of 1919

and the

Greenwich Village Follies

in 1924. During these years the already wealthy Porter—despite his profligacy an heir to his grandfather’s fortune—grew still wealthier when he married the socialite and famous beauty Linda Lee Thomas in 1919. In 1924 the Porters moved to Italy where they would soon launch three years of lavish party-throwing and party-going in their Venetian palazzos. On numerous such occasions the expatriate songwriter would entertain his friends with his witty lyrics and melodies. Near the end of this partying, Porter in 1927 auditioned unsuccessfully for Vinton Freedley and Alex Aarons, the producers of several Gershwin hit musicals and the future producers of four Porter shows starting with

Anything Goes

. When the following year Rodgers and Hart were preoccupied with

A Connecticut Yankee

, Porter was easily persuaded to leave Europe and bring

Paris

to New York.

Anything Goes

would arrive six years and many perennial song favorites later.