Empires of the Sea - the Final Battle for the Mediterranean 1521-1580 (11 page)

Read Empires of the Sea - the Final Battle for the Mediterranean 1521-1580 Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Tags: #Military History, #Retail, #European History, #Eurasian History, #Maritime History

The corsairs’ tactics were soon horribly familiar. A few galliots might loiter offshore, below the rim of the horizon, sitting out the heat of the day. A captured fishing boat would be sent in to scout the coast, maybe with a local renegade to identify suitable targets. In the small hours of the morning the corsairs would make a move, the black, low-slung shapes of the vessels cutting the night sea beneath a sprinkle of stars. There were no lanterns; the Christian galley slaves were gagged with cork dummies to prevent them from calling out. When the prows touched the beach, the corsairs would hit the village at speed; doors were kicked in and the occupants dragged naked from their beds, the church bell rope slashed to forestall an alarm; a few screams and dog barks would echo in the square and a confused straggle of captives were marched down to their own beach and hustled aboard; then they would be gone. “They grabbed young women and children,” recalled a Sicilian villager of one such raid, “they snatched goods and money, and in a flash, back aboard their galleys, they set their course and vanished.” The terror lay in the surprise.

BY THE MID-CENTURY

the Mediterranean was a sea of disappearances, a place where people working the coastal margins simply vanished: the lone fisherman setting out in his boat; a shepherd with his flock on the seashore; laborers harvesting corn or tending vines, sometimes several miles inland; sailors working a small tramp ship around the islands. Once seized they could be in the slave mart at Algiers in a couple of days—or they could be subjected to a lengthy cruise in pursuit of other prizes. Those who weakened or died en route would be dumped overboard.

In a particularly cruel twist, the captives might reappear at their home village a day or two later. The raiders would materialize offshore, hoist a flag of truce, and display the victims for ransom. The grieving relatives would be given a day to raise funds; the families might mortgage their fields and boats to the local moneylender and enter a spiral of inescapable debt. If they failed, the hostages would be gone forever. The illiterate peasantry too poor to be ransomed seldom saw their birthplace again.

The sudden terror of these visitations cast a profound dread over the Christian sea. Those who were taken, such as the Frenchman Du Chastelet, seized in the seventeenth century, never forgot the trauma of their capture. “As to me,” he wrote, recalling the nightmarish moment, “I noticed a great Moor approaching me, his sleeves rolled up to his shoulders, holding a sabre in his large hand of four fingers; I was left without words. And the ugliness of this carbon face, animated by two ivory eyeballs, moving about hideously, terrified me a good deal more than were frightened the first humans at the sight of the flaming sword at the door of Eden.”

This was a terror sharpened by racial difference; across the narrow sea two civilizations communicated through abrupt acts of violence and revenge. Europe was on the receiving end of the slavery it was starting to inflict on West Africa—though the numbers slaved to Islam far exceeded the black slaves taken in the sixteenth century, and where Atlantic slaving was a matter of cold business, in the Mediterranean it was heightened by mutual religious hatred. The Islamic raids were designed both to damage the material infrastructure of Spain and Italy and to undermine the spiritual and psychic basis of Christians’ lives. The ransacking of tombs and the ritual desecration of churches that Jérome Maurand witnessed in 1544 were acts of profound intention. The Italian poet Curthio Mattei mourned “the outrage done to God”—the holy images skewered to the floor with daggers, the mocking of the sacraments and altars. Mattei was equally appalled by the disinterring of corpses and the destruction of generations of past people: “The bones of our dead are not secure underground…dozens of years after death.” The corsairs entered Italian folklore as agents of hell, and what made it more difficult to bear was that as often as not Satan’s emissaries were renegade Christians who had defected to Islam through circumstance or choice, and who were extremely well placed to maximize damage on their native lands.

IN THIS ATMOSPHERE,

Charles’s failure to retake Algiers in 1541 assumed a grave significance. The city, now protected by a breakwater and powerful defenses, became the center of piracy. It was a gold rush town, a place where a man might dream of becoming as rich as Barbarossa. Adventurers, freebooters, and outcasts came from across the impoverished sea and from both sides of the religious divide to try their luck at “Christian stealing.” The city resembled in part a gaudy bazaar where humans and booty were bought and sold, in part a Soviet gulag. Thousands of prisoners were kept in slave pens—the dark, crowded, fetid converted bathhouses—from whence they would be taken daily in chains to work. Wealthy captives such as the Spanish writer Cervantes, held in Algiers for five years, might enjoy tolerable conditions, awaiting liberation through ransom. The poor would lug stones, fell timber, dig salt, build palaces and forts, or, worst of all, row galleys until disease, abuse, and malnourishment finished them off.

It is impossible to know how many slaves were being taken in the decades after 1540, but it was not a one-way trade. Both sides were engaged in “man-taking” throughout the whole length of the sea, and if Islam was in the ascendancy, there were small correctives. The Knights of Saint John were ruthless slavers, particularly La Valette, the French knight who had fought as a young man at Rhodes. Putting out a small force of heavily armed galleys from Malta, the knights returned to their old haunts in the Aegean, disrupting the Ottoman sea-lanes between Egypt and Istanbul. They could be as unscrupulous as any corsair on the high seas. Jérome Maurand reached the Venetian island of Tinos shortly after a visit by a knight with some ships. The islanders had greeted the visitors “as friends and Christians,” until one morning, after most of the island men had left the town to work in the fields, “this Knight and his men, seeing that there were only a few men at the castle, killed them, sacked the castle, and took away the women, boys, and girls as slaves.” This treacherous act soon got its own comeuppance; the knight was in turn seized by Turkish corsairs and taken off to Istanbul, where Maurand was in time to witness his execution. Changes of fortune could be abrupt.

The knights were not alone; any small-scale Christian pirate might try his hand at raiding the eastern sea; Livorno and Naples on the Italian coast had active slave markets. Muslims disappeared into the Malta slave pens or the pope’s imperial galleys, but their numbers were far fewer than those taken to the Maghreb or Istanbul. There is a vast literature of Christian slave narratives; about the Muslims almost nothing. Occasional muffled accounts of personal suffering break the general silence. In the late 1550s Suleiman was bombarded by tearful requests from a woman called Huma for the restoration of her children, taken on a voyage to Mecca by the Knights of Saint John. The two daughters had been abducted to France, converted to Christianity, and married off. Distraught and persistent, Huma was a familiar figure in the Istanbul streets, trying to push a petition into the sultan’s hand as he rode by. Twenty-four years after their disappearance, Sultan Murat III could still write that “the lady named Huma has time and again presented written petitions to our imperial stirrup.” As far as we know the girls never came back; a further brother probably died at the oars of a Malta galley. There were countless thousands of such small tragedies on both sides of the religious divide, familiar tales of abduction and loss.

THE INSTRUMENT OF ALL

this chaotic violence was the oared galley. These fast, fragile, low-slung racing craft were the war machines of the Mediterranean, bred by the conditions of the sea. They dictated absolutely how, where, and when wars could be fought. The advantages of a shallow draft allowed the vessels to be easily beached for amphibious operations; they could lurk in ambush close to the shore and spin on a sixpence around a lumbering sailing ship, whose powers of maneuver were limited by the sea’s uncertain winds. At the same time, the galleys’ extraordinarily poor seaworthiness and dependence on continuous supplies of fresh water for the rowing crews tied them umbilically to land. Galleys needed to put ashore every few days, which meant their range of operation was limited and their deployment strictly seasonal; winter storms ensured that warfare was suspended every year between October and April. Crucially, the dynamo of maritime war was human labor; in all the motivations for slaving in the sixteenth century, snatching men for the rowing benches assumed an important role.

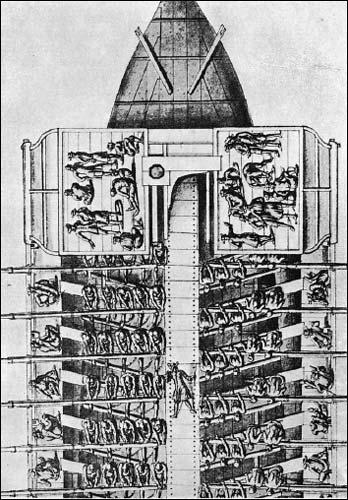

In the heyday of Venetian sea power in the fifteenth century, galleys had been rowed by volunteers; by the sixteenth, the muscle power was generally conscripted. The Ottoman navy relied heavily on an annual levy of men from the provinces of Anatolia and Europe, and everyone employed chained labor—captured slaves, convicts, and, in the Christian ships, paupers so destitute they sold themselves to the galley captains. It was these wretches, chained three or four to a foot-wide bench, who made sea wars possible. Their sole function was to work themselves to death. Shackled hand and foot, excreting where they sat, fed on meagre quantities of black biscuits, and so thirsty they were sometimes driven to drink seawater, galley slaves led lives bitter and short. The men, naked apart from a pair of linen breeches, were flayed raw by the sun; sleep deprivation on the narrow bench propelled them toward lunacy; the stroke keeper’s drum and the overseer’s lash—a tarred rope or a dried bull’s penis—whipped them beyond the point of exhaustion during long stretches of intensive effort when a ship was trying to capture or escape another vessel. The sight of a galley crew at full stretch was as brutal as any a man could wish to be spared. “That least tolerable and most to be dreaded employment of a man deprived of liberty,” wrote the eighteenth-century English historian Joseph Morgan, conjuring up the vision of “ranks and files of half-naked, half-starved, half-tanned, meagre wretches, chained to a plank, from whence they remove not for months at a time…urged on, even beyond human strength, with cruel and repeated blows, on the bare flesh, to an incessant continuation of the most violent of all exercises.” “God preserve you from the galleys of Tripoli,” was a customary vale-diction to men putting to sea from a Christian port.

Men at the rowing benches

Disease could decimate a fleet in weeks. The galley was an amoebic death trap, a swilling sewer whose stench was so foul you could smell it two miles off—it was customary to sink the hulls at periodic intervals to cleanse them of shit and rats—but if the crew survived to enter a battle, the chained and unprotected rowers could only sit and wait to be killed by men of their own country and creed. The nominally free men who made up the bulk of the Ottoman rowing force fared little better. Levied by the sultan in large numbers from the empire’s inland provinces, many had never seen the sea before. Inexperienced and inefficient as oarsmen, they succumbed in large numbers to the terrible conditions.

One way or another the oared galley consumed men like fuel. Each dying wretch dumped overboard had to be replaced—and there were never enough. Official Spanish and Italian memoranda report monotonously on the shortage of fodder for the benches, so that the supply of ships often outstripped the resources to power them, as in the case of a sudden disaster that overcame the galleys of the Knights of Saint John in 1555.

On the night of October 22, their four vessels were riding safely at anchor in their secure harbor in Malta. The commander of the galleys, Romegas—the Order’s most experienced naval captain—was asleep at the rear of his ship when a freak whirlwind whipped across the sea, snapped the ships’ masts, and flipped the galleys over. When dawn broke, all four galleys were floating upside down on the gray water. Rescuers put out in boats to hunt for signs of life and inspect the damage; when they heard a dull tapping coming from one of the ships, they smashed a hole in the hull and peered downward into the dark. Out promptly hopped the ship’s monkey, followed by Romegas, who had spent the night up to his shoulders in water in an air pocket. It was only when the vessels were righted with the help of buoyant air barrels that the full horror of the event became clear; the corpses of three hundred drowned Muslim slaves still chained to the benches floated in the water like ghosts. Repair and replacement of the vessels was a manageable problem; it was securing new crews that was the real difficulty. The pope threw open the episcopal prison in Naples to supply some of the number; the knights then had to take some of their ships to snatch more slaves to fill the empty spaces. It was the same for both sides: much of the raiding was undertaken solely to make such raids possible. The violence was self-perpetuating. The galleys created their own need for war.