Embers of War (85 page)

Authors: Fredrik Logevall

Tags: #History, #Military, #Vietnam War, #Political Science, #General, #Asia, #Southeast Asia

IV

THE ASSAULT BEGAN ON MAY 1, AT THE USUAL TIME: LATE AFTERNOON

. All day long evidence had accumulated in General de Castries’s command bunker that something was afoot, and by early afternoon the deadly smell of all-out assault hung in the air. Probing attacks down the trench lines were being made in greater strength, and radio intercepts detected the presence of Viet Minh battalions in concentration. The previous three nights had seen more downpours, and on April 29 some parts of the garrison reported three feet of standing water in the trenches. Their boots and clothing perpetually soaked, the men were also hungry, for everyone was now on half rations. April 30 brought a modicum of good news, in the form of an agreement by the American crews from CAT to resume their C-119 flights, in exchange for a promise from the French Air Force to do a better job of suppressing enemy flak (a promise it failed to keep). Supply drops increased dramatically that day and on May 1, and when the assault began, there was again three days of food available, along with desperately needed ammunition.

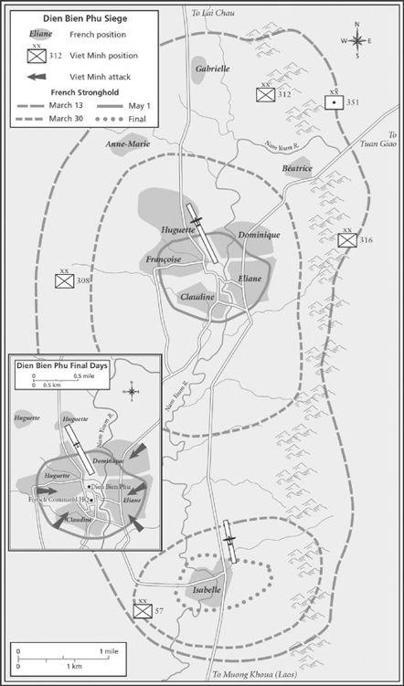

Just before five o’clock in the afternoon, the artillery barrage commenced. More than one hundred Viet Minh field guns opened up over the whole area of the camp. Bunkers and soggy trenches collapsed under the bombardment, many of their occupants buried alive. After three hours, the firing slackened, whereupon the entire 312th and 316th Divisions stormed up the eastern hill positions of Eliane and Dominique and the 308th targeted Huguette. Dominique 3, defended by a motley mix of Algerians and Tai, fell quickly, and by 2

A.M

. Eliane 1 had succumbed as well. In nine hours of fighting, the garrison had lost 331 killed or missing. Was this the beginning of the end? Senior French commanders feared it was. Colonel Langlais wired Hanoi soon after the assault began: “No more reserves left. Fatigue and wear and tear on the units terrible. Supplies and ammunition insufficient. Quite difficult to resist one more such push by Communists, at least without bringing in one brand-new battalion of excellent quality.”

26

General de Castries followed with his own message, sent to General Cogny shortly before midnight: “In any case extremely heavy losses require as of tomorrow night a solid new battalion. Urgent reply requested.”

27

Cogny obliged, sending in part of his last remaining airborne force, the First Colonial Parachute Battalion, the next night. More ammunition and supplies were dropped as well, but as on previous nights a high proportion of the tonnage—in this case roughly a third—landed in Viet Minh hands, or in sections of the camp too dangerous to enter for fear of snipers, with the result that the packages were left unretrieved. The new troops were a welcome sight, but they could not make up the heavy losses suffered by the other battalions. Intense fighting continued, with the Viet Minh suffering colossal losses but pressing forward relentlessly. Slowly the French perimeter was bent inward and compressed, as the mortar shells rained down on the French positions. On the night of May 4, de Castries and his staff had to listen helplessly as Huguette 4, defended by eighty legionnaires and Moroccan riflemen against an entire Viet Minh regiment plus four additional battalions (roughly three thousand men), fell after a desperate hours-long stand. At 3:55

A.M

. a terse radio message from one of the last surviving officers announced that only a few men remained on their feet. His listeners then heard his death cry, uttered as he was shot by Viet Minh troops who had fought their way into his trench.

28

After sunrise that morning, de Castries cabled Cogny the news of the enemy advance in the face of enormous losses and asked for the immediate dispatch of the remainder of the First Colonial Parachute Battalion. The concluding passage stands out for its unsparing assessment of the situation at that moment, fifty-three days into the battle:

The provisions of all kinds are at their lowest; for fifteen days they have been reduced little by little. We don’t have enough ammunition to stop enemy attacks or for harassing fire that must continue without pause; it appears that no effort is being made to remedy this situation. I am told of the risks to the aircrews, but every man here runs infinitely greater risks—there cannot be a double standard. The night drops must begin at 8

P.M

. instead of 11

P.M

. The morning hours are lost because of the fog, and due to the planning of night drops with long intervals between aircraft the results are ridiculous. I absolutely need provisions in massive quantities.

The very small state of the center of resistance, and the fact that the elements holding the perimeter can’t leave their shelters without coming under fire from snipers and recoilless rifles, means that more and more of the cases dropped are no longer retrievable. The lack of vehicles and coolies oblige me to use extremely exhausted units for recovery tasks; the result is detestable. It also causes losses. I cannot even count on retrieving half of what is dropped, although the quantities sent to me represent only a very small portion of what I have requested. This situation cannot go on.

I insist, once more, on the broad authority that I have requested in the matter of citations. I have nothing to sustain the morale of my men who are being asked for superhuman efforts. I no longer dare to go see them with empty hands.—end—

29

De Castries did not hold out much hope that the plea would do any good. Hitherto Hanoi had not been able to provide remotely enough supplies; why should that change now? Headquarters was indeed now giving him authorization to consider a possible breakout attempt from the valley, a sure sign in de Castries’s mind that Hanoi was fast losing faith that the situation could be salvaged. The plan bore the unfortunate code name Albatross and called for the able-bodied survivors to break through enemy lines to the southeast at nightfall, under cover of artillery fire, air support, and small arms fire from the walking wounded, who would be left behind, along with more seriously wounded and the hospital staff. The breakout group would make for the Laotian frontier and would rendezvous with the Condor column about ten days thence, somewhere near Muong Nha. Navarre welcomed Albatross as an alternative to leaving the garrison to die, but Cogny was unenthusiastic. The escapees were sure to be routed, he argued, if not at the initial breakout, then soon thereafter; they were too exhausted, and the enemy too entrenched, for it to be otherwise. The Viet Minh would make propaganda hay of the rout, and the French press would not look kindly on such a nonheroic action. But Cogny agreed it should be left to General de Castries to decide whether to attempt the breakout once on-the-spot resistance had become hopeless.

30

Strangely enough for a commander whose position was more precarious with each passing hour, whose men were fighting for their very lives, de Castries had ample time to consider Albatross during the daylight hours of May 5. With all the reserves committed, and with ammunition levels low, there was simply not much left to plan or direct other than an attempted breakout. Still, he hardly relished the opportunity. Told by Cogny that under no circumstances should he surrender, he now faced the delicate task of preparing for a potential breakout without shattering the morale of his troops. He summoned his senior subordinates to his command post and briefed them on the plan. No one expressed enthusiasm, but all agreed it might have to be implemented depending on what transpired in the coming days.

Not yet, though. The situation was bad but not yet desperate enough to initiate an escape plan that even its few proponents considered risky in the extreme. The enemy continued to suffer vastly greater casualties and surely had his own supply problems; if the fortress could hold out a few more days, Giap might have to call a halt and withdraw, at least temporarily. The mood brightened further on the morning of May 6, with the largest supply drop in almost three weeks, a total of almost 196 tons. Ninety-one volunteers also parachuted in during the early hours, many of them Vietnamese. (These paras would be the last reinforcements to reach Dien Bien Phu.) Meanwhile a weak Viet Minh probe against Eliane 3 was easily repelled, and a more serious attack on two Huguette positions was also beaten back.

31

Soon the fog lifted to reveal that most rare of sights in these weeks: clear blue skies. Seemingly on cue, the air above the valley filled with aircraft, bringing further hope to de Castries’s desperately weary men. With French Air Force and Navy bombers and fighters concentrating on flak suppression, some transport pilots volunteered to come in lower to achieve better success releasing their loads over the drop zone. Art Wilson, a CAT pilot carrying ammunition for Isabelle, took a hit from a 37mm flak shell in his tail and lost elevator control but completed his run and made it safely back to base at Cat Ni.

Next into the circuit was another CAT pilot, Captain James B. McGovern. A giant bear of a man—his nickname was “Earthquake McGoon,” after a hulking hillbilly in the comic strip

Li’l Abner

, and his pilot seat had to be specially designed to accommodate his massive frame—McGovern was a legend among Indochina pilots, just as he had been a legend among Chennault’s Flying Tigers in China in World War II. With a booming voice and an insatiable appetite for food and drink, the native of Elizabeth, New Jersey, was a fixture at bars from Taipei to Saigon, and he did not hesitate when offered the chance to fly the Dien Bien Phu run. This was his forty-fifth mission to the remote valley, and he had with him copilot Wallace Buford of Ogden, Utah, as well as two French crewmen. As McGovern eased the C-119 in for the final run over the drop zone, he was hit in the port engine; he feathered it quickly, only to have a second 37mm shell tear into one of the plane’s tail booms. With six tons of ammunition aboard, the aircraft was a gigantic bomb, and the two pilots fought desperately to regain control. They made it out of the valley to the southeast, the plane yawing badly, but it was hopeless. “Looks like this is it, son,” McGovern coolly radioed another pilot, seconds before the plane plummeted to earth behind the Laotian border, cartwheeled, and exploded in a huge black cloud.

32

The following day a telegram from the American consulate in Hanoi informed Washington that, according to French officials, “a C-119 was shot down yesterday by ack ack fire south of Dien Bien Phu. Entire crew, composed of two CAT American pilots (names unknown) and two French crew members, reported lost.”

33

Since March 13, thirty-seven CAT pilots had made nearly seven hundred air-drops over the basin, the importance of which to the garrison’s survival would be next to impossible to exaggerate. McGovern and Buford would be the only ones to lose their lives.

34

V

ABOUT THE TIME MCGOVERN’S PLANE ENTERED THE DROP ZONE

on that fateful final run, the French command in the camp below received a shocking message from Hanoi. Cryptographers had picked up news of the date and time of the final Viet Minh assault: It was to be launched shortly after sundown that very day, May 6. For General de Castries and his subordinates, this was a bombshell of a different kind. They would not be prepared, they knew. True, more ammunition had come in overnight, but many of the parachuted packets would not be retrievable until after dark, by which point it might be too late. The enemy trench works had drawn ever closer, and the garrison was acutely undermanned. But it would be vital to persevere for the next few days, especially with a column en route from Laos and with the Geneva Conference about to commence discussion of Indochina. “We must hang on,” Colonel Langlais told a gathering of officers at ten

A.M

. “We must force a draw. On the other side they’re just as exhausted as we are.”

35

If the defenders could withstand the assault and in the process inflict heavy losses on Giap’s forces, he might choose to halt the proceedings for a period of weeks, or might be compelled to do so by a cease-fire agreement at Geneva. If, on the other hand, the Viet Minh commander succeeded in overwhelming the last strongpoints, he might be perceived far and wide as the victor in Indochina. These broader considerations were hardly the central concern of the officers in the bunker that morning, but they grasped that the stakes were huge—that on the defense of their tiny patch of territory in the coming days could hinge the entire war.

What a task they faced! Giap’s attacking force consisted of four infantry divisions, plus thirty artillery battalions and some one hundred guns. In response, the defenders could offer very little except the courage and fortitude borne of desperation. In this respect it was to their advantage that their perimeter had shrunk: It now consisted mostly of portions of Huguette, Claudine, and Eliane, perhaps one thousand yards square, plus the isolated Isabelle three miles to the south. To cover the approach to the hospital, which that morning held more than sixteen hundred wounded, an improved strongpoint christened Juno had been created between Claudine and Eliane. Total troop strength stood at roughly 4,000, though in terms of infantry in the central sector it was closer to 2,000. There were Foreign Legion and Vietnamese parachutists, Moroccan Rifles, Tai from various dissolved units, French paratroop battalions (half of them Vietnamese), Arab and African gunners, and, down on Isabelle, still some Algerians. The greatest concentration of men, some 750 parachutists, was deployed at the point of maximum import and danger, the top of Eliane.

36