Elizabeth the Queen (32 page)

Read Elizabeth the Queen Online

Authors: Sally Bedell Smith

In the evenings, the family has a long tradition of playing vigorous games such as “Kick the Can” and “Stone,” with guests as well as members of the household. Twice each autumn they gather in the castle ballroom for the Ghillies’ Ball, where the men wear black tie and kilts, and the women dress in tiaras, long gowns, and tartan sashes fastened with diamond brooches. As military musicians play their tunes, the Queen and her family whirl through intricate reels and veletas with gamekeepers, ghillies, footmen, and maids—a montage of sights and sounds from an earlier century.

Balmoral echoes personal memories for Elizabeth II—of childhood, the war, Philip’s proposal—and it represents a continuum back to Queen Victoria, even a connection to the Bavarian landscapes of her ancestors, which are conjured up by Prince Albert’s adaptations of architectural styles from Germany. “At Balmoral, she never forgets she is Queen,” said a Scottish cleric who visited there often. “

You

never forget she is Queen.” All guests, including relatives who call her Lilibet and longtime friends, bow and curtsy when they greet her in the morning, and when she retires at night.

Yet her life in the Highlands offers her a taste of normality, and a sense of freedom. She goes into the nearby village of Ballater and stands in line at the local shops. She does household chores in remote cabins. She dresses unpretentiously in well-worn clothes—always the tartan skirts (never pants except for riding or field sports), but also plain black shoes with low socks, a buttoned-up cardigan with another sweater layered on top, and her ubiquitous strand of pearls. When she has downtime, she reads for pleasure, particularly historical novels—not, to anyone’s knowledge, the seven volumes of Proust, “engrossed in the sufferings of Swann … while in the wet butts on the hills the guns cracked out their empty tattoo,” as imagined by Alan Bennett in

The Uncommon Reader

, his droll novel about the Queen. For many years she would choose from a batch of volumes recommended by the Book Trust, a British charity founded in 1921 to promote books and reading. But the principal escape is through her primal communion with the countryside. “You can go out for miles and never see anybody,” she has said. “There are endless possibilities.” It is a world where she can live life “to the fullest.”

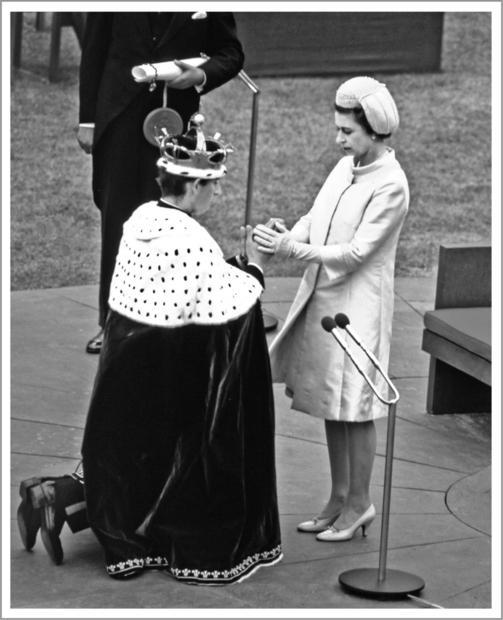

“By far the most moving and

meaningful moment came when I

put my hands between Mummy’s

and swore to be her liege man of

life and limb and to live and die

against all manner of folks.”

Prince Charles paying homage to his mother after his investiture as Prince of Wales, July 1969.

Reginald Davis MBE (London)

NINE

Daylight on the Magic

Daylight on the Magic

I

N THE 1960S, THE

Q

UEEN BECAME A MORE RELAXED AND CONSISTENTLY

engaged mother with her second set of children. “Goodness what fun it is to have a baby in the house again!” she said after Edward’s birth in 1964. Mary Wilson recalled that on Tuesday evenings, as the prime minister’s audience was drawing to a close, her husband “was very impressed by the fact that she always wanted to be there for the children’s baths.”

Elizabeth II felt comfortable spending more time in the nursery in part because she got along so well with Mabel Anderson. The principal nanny for Charles and Anne, Helen Lightbody, had been an autocrat nearly fifteen years older than the Queen, fierce in upholding her authority over the children. Lightbody had favored Charles over Anne, who bore the brunt of her reprimands. Displeased by her harsh treatment of his spirited daughter, Prince Philip had arranged for Lightbody’s departure.

Mabel Anderson was a year younger than the Queen, and she had an affectionate and flexible nature as well as a firm sense of right and wrong. The Queen was not intimidated by Anderson as she had been by Lightbody, and the two women worked together with the younger children. When Anderson took time off, the Queen felt relaxed enough to stay in the nursery with Andrew and Edward, putting on an apron for their baths and lulling them to sleep. Some critics have questioned whether she indulged Andrew and Edward too much, making up for not having spent more time with her older children.

Although still not inclined toward hugging and kissing, she showed more of her playful streak with Andrew and Edward. They knew Buckingham Palace was an office where the priorities were, in Andrew’s words, “work and responsibilities and duties.” Still, the passage outside the nursery echoed with the thuds of tennis balls and footballs barely missing the glass cabinets. When Sir Cecil Hogg, the family’s ear, nose, and throat doctor for more than a dozen years, was paying a house call at the Palace, “he could hear the younger children rampaging in another room,” recalled his daughter Min Hogg. “One of the children rushed into her bedroom and the Queen laughed and said to him, ‘You and your monsters!’ ”

At Windsor Castle, which the boys considered their real home, they would race their bicycles and play “dodge-ems” with pedal cars along the gilded Grand Corridor, with its twenty-two Canalettos and forty-one busts on scagliola pedestals, or outside on the gravel paths. If the boys fell down, the Queen would “pick us up and say, ‘Don’t be so silly. There’s nothing wrong with you. Go and wash off,’ just like any parent,” Andrew recalled. At teatime, they would sit with their parents to watch the BBC’s

Grandstand

sports program on Saturdays and the Sunday Cricket League. “As a family we would always see more of the Queen at weekends than during the week,” said Andrew.

Charles and Anne were away at school much of the time during the 1960s. Anne’s experience at her prestigious boarding school in Kent, Benenden, was much happier than her older brother’s. She had her father’s thick skin and lacerating wit to protect her from mean girls—whom she called a “caustic lot.” Her headmistress noted Anne’s ability to “exert her authority in a natural manner without being aggressive.” Like Prince Philip she was “extremely quick to grasp things” as well as impatient with those who could not. At five foot six, she was taller than her mother, with a trim and alluring figure. She had the Queen’s porcelain complexion, but stronger features including a pendulous lower lip that gave her a sulky demeanor. As a teenager she wore her hair long, which softened her appearance.

Despite her sharp intelligence, Anne had scant interest in academics, and her examination results weren’t strong enough for admission to a university. She enjoyed pushing the envelope physically, another trait inherited from her father, who taught her to sail in the rough waters off the Scottish coast and competed with her in the Cowes regatta. Anne wrote that sailing gave her “an utterly detached sensation that I have only otherwise experienced on a galloping horse … testing your skill against Nature, your ideals and the person you would like to be.” Having ridden since the age of two when she first sat on a white pony named Fum, horses became Anne’s passion. After graduating from Benenden in 1968 at age eighteen, she focused on competing in the arduous equestrian sport of three-day eventing.

When Charles was approaching his final year at Gordonstoun, his parents convened a meeting over dinner in December 1965 to map out the appropriate future for the heir to the throne, who was not included in the discussion. Three previous kings—Edward VII, Edward VIII, and George VI—had taken courses at Oxford and Cambridge but had never earned degrees. Since neither Philip nor Elizabeth II had university experience, they relied on the counsel of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Michael Ramsey; Prime Minister Harold Wilson; Dickie Mountbatten, then chief of the Defence Staff; Robin Woods, the dean of Windsor; and Sir Charles Wilson, principal and vice-chairman of Glasgow University and chairman of the Committee of Vice-Chancellors.

For several hours, they discussed various alternatives as the Queen listened. Harold Wilson advocated Oxford, but Dickie preferred Trinity College at Cambridge and the Royal Naval College at Dartmouth, followed by the Royal Navy, a plan the family eventually adopted a year later. Charles was pleased to be attending Cambridge, if only because it was so near the shooting at Sandringham, with its “crème de la crème of wild birds.” When he enrolled in the autumn of 1967, he was the first royal student to live in rooms at the college. Former conservative politician Rab Butler, then the master of Trinity, was his mentor.

As a general principle, the Queen sought to expose Charles and Anne to challenging situations and preferred to talk to them “on level grown-up terms,” one writer observed in 1968. “I remember the patience Prince Charles showed when he was around all those adults,” said Mary Wilson. At one Buckingham Palace luncheon in honor of a delegation from Nigeria, Cynthia Gladwyn found him “charming … with his desire to please, his tentative interest in everybody, his wild-rose coloring … his sensitivity contrasting with his father’s lack of it.” Within the requirements of their royal existence, Elizabeth II encouraged her older children to work their way through difficulties, learning to think for themselves—an approach some intimates criticized as too lax.

“Right from the beginning, they were given a tremendously free rein,” a lady-in-waiting told journalist Graham Turner, who wrote a damning account of the Queen’s mothering skills. “Because of that early independence, it became more like a club than a family,” the lady-in-waiting continued. “Charles and Anne, in particular, would also have thought, ‘Don’t let’s bother Mummy, she’s got enough on her plate already.’ And she wouldn’t have expected anything else.… The Queen and Prince Philip brought up the children very toughly.”

Princess Anne countered that “it just beggars belief” to suggest that her mother was aloof and uncaring. “We as children may have not been too demanding, in the sense that we understood what the limitations were in time and the responsibilities placed on her as monarch in the things she had to do and the travels she had to make,” said Anne, “but I don’t believe that any of us, for a second, thought she didn’t care for us in exactly the same way as any mother did.… We’ve all been allowed to find our own way and we were always encouraged to discuss problems, to talk them through. People have to make their own mistakes and I think she’s always accepted that.”

Of all the Queen’s children, Anne was the most secure and self-sufficient. The mother-daughter relationship ran smoothly, largely because they shared such a strong bond through horses. And since Anne was cut from Prince Philip’s cloth—feisty, confident, and straightforward—she could deal with his tough love.

Charles, however, struggled with his father’s demands and expectations. He had shown his mettle in taking on physical challenges, notably during two terms in the Australian outback at the Timbertop school. On returning to Gordonstoun he achieved the same “Guardian” leadership position his father had held. He even mimicked some of his father’s mannerisms—walking with one arm behind his back, making light jokes to put others at ease, tugging at his jacket sleeve, clasping his hands, or jabbing his right forefinger for emphasis.

But Philip continued to offer more criticism than praise to his son, deepening Charles’s insecurity. Philip couldn’t reconcile their “great difference,” as he once put it. “He’s a romantic, and I’m a pragmatist.” Although Charles “was too proud to admit it,” wrote Jonathan Dimbleby, “the Prince still craved the affection and appreciation that his father—and his mother—seemed unable or unwilling to proffer.… In self protection, he retreated more and more into formality with his parents.” When it came to guidance about Charles’s future, father and son minimized conflict by communicating through crisply composed letters.

It was at Sandringham and Balmoral that the children found common ground with their parents. To the Queen, Sandringham represents “an escape place, but it is also a commercially viable bit of England. I like farming … I like animals. I wouldn’t be happy if I just had arable farming.” The Queen and Prince Philip deeply imprinted their four children with knowledge of flora and fauna, and they all came to appreciate, as Anne wrote, the “pure luxury” of hours on horseback across the “miles of stubble fields around Sandringham,” as well as “the autumn colours of the rowans and silver birches, the majesties of the old Scots pines” of Deeside. Charles was so inspired that at age twenty he wrote a book for his younger brothers about the mythical “Old Man of Lochnagar” who lived in a cave on the mountain above Balmoral, tried to travel to London but returned to the solitude of his “special” home.