Elizabeth M. Norman (2 page)

Read Elizabeth M. Norman Online

Authors: We Band of Angels: The Untold Story of American Nurses Trapped on Bataan

Tags: #World War II, #Social Science, #General, #Military, #Women's Studies, #History

They learned this—the notion of strength in numbers—as military women. In the ranks nothing is more important than “unit cohesiveness.” Masses of arms and men win wars, not the impulsive deeds of heroes. As it turned out, the “group” saved their lives. Their collective sense of mission, both as nurses and as army and naval officers, allowed them to survive when stronger people faltered. In prison not one of the nurses died of disease or malnutrition, while more than four hundred other internees perished. In that context their survival as a group was extraordinary.

I

N SOME WAYS

the women in this book are typical of their time—they were born, most of them, in the early twentieth century, the daughters of immigrants and farmers and shopkeepers, obedient girls who studied

long and hard in school, then came home to hours of chores and housework. In other ways, however, they were distinct, for early on they learned or perhaps were taught the virtue of independence and the autonomous life.

In some the ethos of independence bred ambition, in others rebellion. As teenagers they started to reject the roles society had set for them. They had watched their mothers struggle—long hours cooking, sewing, washing, hoeing and milking cows—and they decided they wanted something more, something different than an early marriage, a house full of babies and a life over a cast-iron stove.

Teaching and office work held little appeal—the former meant taking care of someone else’s children, the latter someone else’s man—so they entered the only other profession open to them, nursing.

After nursing school and a stint on a ward, they joined the army or the navy. No subculture in American society was more intolerant of women than the military, but signing on to a life of restrictions and regulations seemed to make a strange kind of sense for these nonconformists. In a time of economic depression, when thousands were standing on breadlines, the nurses had jobs, and good ones. More to the point, the military gave the women a way to get what each really wanted—adventure. And no post was more exotic, more filled with the possibility for encounters, escapades and romance than the lush, tropical islands of the Philippine archipelago.

The dazzling flowers, the sprawling white stucco haciendas and pristine beaches of Manila seemed almost dreamlike set against the frugal venues of their youth. And a light workload in a sleepy military hospital left plenty of time for play—afternoons on the golf course or the tennis courts, evenings waltzing under an Oriental sky. All they needed was the right wardrobe (a uniform, a bathing suit and an evening gown), the right dance steps, a little dinner-table riposte and repartee, and they were ready for their tour in paradise.

Chapter 1

Waking Up to War

I

N THE FALL

of 1941, while the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy secretly stockpiled tons of materiel and readied regiments of troops to attack American and European bases in the Pacific, the officers of General Douglas MacArthur’s Far East Command in the Philippines pampered themselves with the sweet pleasures of colonial life.

For most, war was only a rumor, an argument around the bar at the officers club, an opinion offered at poolside or on the putting green: let the bellicose Japanese rattle their swords—just so much sound and fury; the little island nation would never challenge the United States, never risk arousing such a prodigious foe.

The Americans had their war plans, of course—MacArthur had stockpiled supplies and intended to train more Filipino troops to fight alongside his doughboys—but most of the officers in the Far East Command looked on the danger with desultory eyes. They were much too preoccupied with their diversions, their off-duty pastimes and pursuits, to dwell on such unpleasant business. To be sure, there were realists in the islands, plenty of them, but for the most part their alarms were lost in the roar of the surf or the late-afternoon rallies on the tennis court.

Worry about war? Not with Filipino houseboys, maids, chefs, gardeners and tailors looking after every need. And not in a place that had the look and sweet fragrance of paradise, a place of palm groves, white gardenias and purple bougainvillea, frangipani and orchids—orchids everywhere, even growing out of coconut husks. At the five army posts and one navy base there were badminton and tennis courts, bowling alleys and playing fields. At Fort Stotsenberg, where the cavalry was based,

the officers held weekly polo matches. It was a halcyon life, cocktails and bridge at sunset, white jackets and long gowns at dinner, good gin and Gershwin under the stars.

W

ORD OF THIS

good life circulated among the military bases Stateside, and women who wanted adventure and romance—self-possessed, ambitious and unattached women—signed up to sail west. After layovers in Hawaii and Guam, their ships made for Manila Bay. At the dock a crowd was often gathered, for such arrivals were big events—“boat days,” the locals called them. A band in white uniforms played the passengers down the gangplank, then, following a greeting from their commanding officer and a brief ceremony of welcome, a car with a chauffeur carried the new nurses through the teeming streets of Manila to the Army and Navy Club, where a soft lounge chair and a restorative tumbler of gin was waiting.

Most of the nurses in the Far East Command were in the army and the majority of these worked at Sternberg Hospital, a 450-bed alabaster quadrangle on the city’s south side. At the rear of the complex were the nurses quarters, elysian rooms with shell-filled windowpanes, bamboo and wicker furniture with plush cushions and mahogany ceiling fans gently turning the tropical air.

From her offices at Sternberg Hospital, Captain Maude Davison, a career officer and the chief nurse, administered the Army Nurse Corps in the Philippines. Her first deputy, Lieutenant Josephine “Josie” Nesbit of Butler, Missouri, also a “lifer,” set the work schedules and established the routines. For most of the women the work was relatively easy and uncomplicated, the usual mix of surgical, medical and obstetric patients, rarely a difficult case or an emergency, save on pay nights or when the fleet was in port and the troops, with too much time on their hands and too much liquor in their bellies, got to brawling.

For the most part one workday blended into another. Every morning a houseboy would appear with a newspaper, then over fresh-squeezed papaya juice with a twist of lime, the women would sit and chat about the day ahead, particularly what they planned to do after work: visit a Chinese tailor, perhaps, or take a Spanish class with a private tutor; maybe go for a swim in the phosphorescent waters of the beach club.

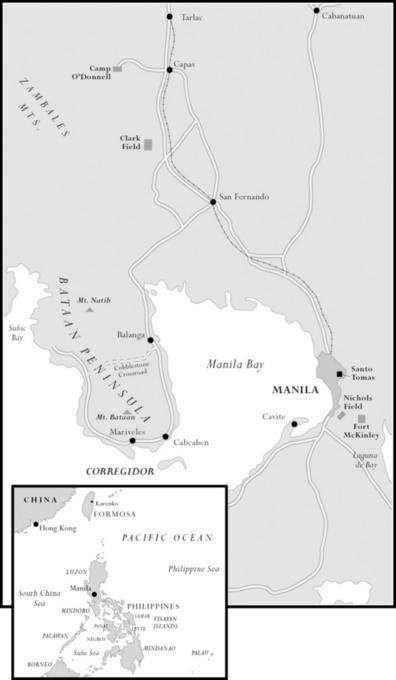

The other posts had their pleasures as well. At Fort McKinley, seven miles from Manila, a streetcar ferried people between the post pool, the bowling alley, the movie theater and the golf course. Seventy-five miles

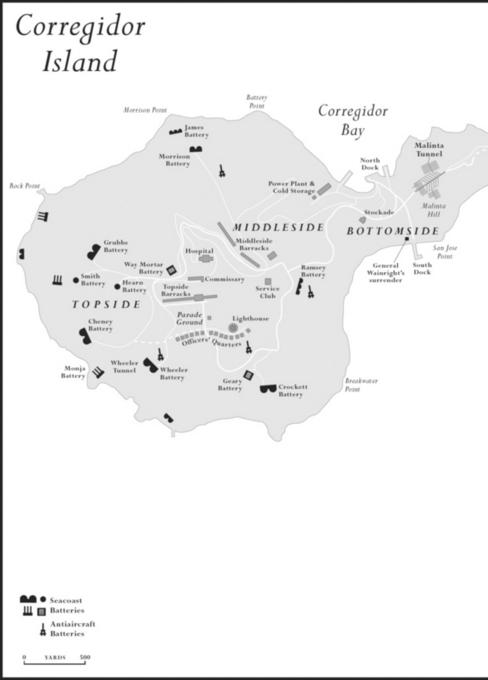

north at Fort Stotsenberg Hospital and nearby Clark Air Field, the post social life turned on the polo matches and weekend rides into the hills where monkeys chattered like children and red-and-blue toucans and parrots called to one another in the trees. Farther north was Camp John Hay, located in the shadow of the Cordillera Central Mountains near Baguio, the unofficial summer capital and retreat for wealthy Americans and Filipinos. The air was cool in Baguio, perfect for golf, and the duffers and low-handicappers who spent every day on the well-tended fairways of the local course often imagined they were playing the finest links this side of Scotland. South of Manila, a thirty-mile drive from the capital, or a short ferry ride across the bay, sat Sangley Point Air Field, the huge Cavite Navy Yard and the U.S. Naval Hospital at Canacao. The hospital, a series of white buildings connected by passageways and shaded by mahogany trees, was set at the tip of a peninsula. Across the bay at Fort Mills on Corregidor, a small hilly island of 1,735 acres, the sea breezes left the air seven degrees cooler than in the city. Fanned by gentle gusts from the sea, the men and their dates would sit on the veranda of the officers club after dark, staring at the glimmer of the lights from the capital across the bay.

Even as MacArthur’s command staff worked on a plan to defend Manila from attack, his officers joked about “fighting a war and a hangover at the same time.” A few weeks before the shooting started, nurse Eleanor Garen of Elkhart, Indiana, sent a note home to her mother: “Everything is quiet here so don’t worry. You probably hear a lot of rumors, but that is all there is about it.”

1

In late November of 1941, most of the eighty-seven army nurses and twelve navy nurses busied themselves buying Christmas presents and new outfits for a gala on New Year’s Eve. Then they set about lining up the right escort.

M

ONDAY

, D

ECEMBER 8, 1941

, just before dawn. Mary Rose “Red” Harrington was working the graveyard shift at Canacao Naval Hospital. Through the window and across the courtyard she saw lights come on in the officers quarters and heard loud voices. What, she wondered, were all those men doing up so early? And what were they yelling about? A moment later a sailor in a T-shirt burst through the doors of her ward.

They’ve bombed Honolulu!

Bombed Honolulu? What the hell was he talking about, Red thought.

2

Across Manila Bay, General Richard Sutherland woke his boss, General Douglas MacArthur, supreme commander in the Pacific, to tell him that the Imperial Japanese Navy had launched a surprise attack on the U.S. Naval Base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Later they would learn the details: nineteen American ships, including six battle wagons, the heart of the Pacific fleet, had been scuttled, and the Japanese had destroyed more than a hundred planes; through it all, several thousand soldiers and sailors had been killed or badly wounded.

After months of rumor, inference and gross miscalculation, the inconceivable, the impossible had happened. The Japanese had left the nucleus of the U.S. Pacific fleet twisted and burning. America was at war and the military was reeling.

Juanita Redmond, an army nurse at Sternberg Hospital in Manila, was just finishing her morning paperwork. Her shift would soon be over. One of her many beaus had invited her for an afternoon of golf and she planned a little breakfast and perhaps a nap beforehand. The telephone rang; it was her friend, Rosemary Hogan of Chattanooga, Oklahoma.

The Japs bombed Pearl Harbor.

“Thanks for trying to keep me awake,” Redmond said. “But that simply isn’t funny.”

“I’m not being funny,” Hogan insisted. “It’s true.”

3

As the reports of American mass casualties spread through the hospital that morning, a number of nurses who had close friends stationed in Honolulu broke down and wept.

“Girls! Girls!” Josie Nesbit shouted, trying to calm her staff. “Girls, you’ve got to sleep today. You can’t weep and wail over this, because you have to work tonight.”

4