Eleanor of Aquitaine: The Mother Queen (20 page)

Read Eleanor of Aquitaine: The Mother Queen Online

Authors: Desmond Seward

At long last, on 4 February 1194, Richard was released, ‘restored to his mother and to freedom’. Those who witnessed Eleanor’s reunion with her son wept at the spectacle. No doubt in her old age she could appear as pathetic as she was formidable. Indeed, in one of those frenzied letters to pope Celestine she had written of herself, with unaccustomed self-pity, as a woman ‘worn to a skeleton, a mere bag of skin and bones, the blood gone from her veins, her very tears dried before they came into her eyes’. She and Richard then began a joyful progress together down the Rhine, via Cologne and Antwerp, where they were splendidly feted. At Cologne the archbishop celebrated a Mass of thanksgiving in the cathedral; the introit began most fittingly, ‘Now I know that the Lord hath sent His angel and snatched me from the hand of Herod’, and every literate man present knew that this was not the introit for the day. At Antwerp they were the honoured guests of the duke of Louvain. Throughout the journey Richard took the opportunity of allying with as many local magnates as possible and especially with those lords in the Low Countries whose lands bordered the territory of the king of France.

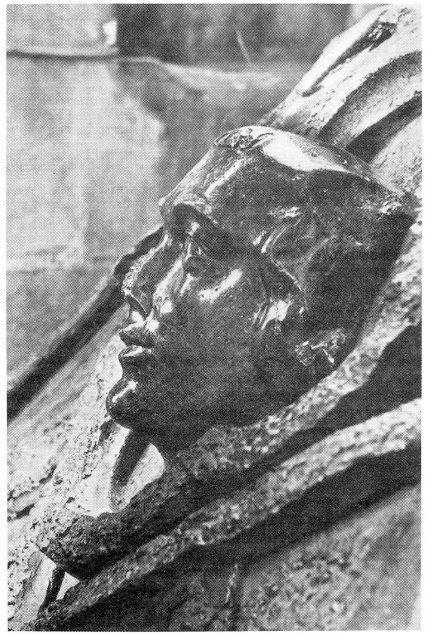

Archbishop Hubert Walter: from his tomb in Canterbury Cathedral.

Courtauld Institute.

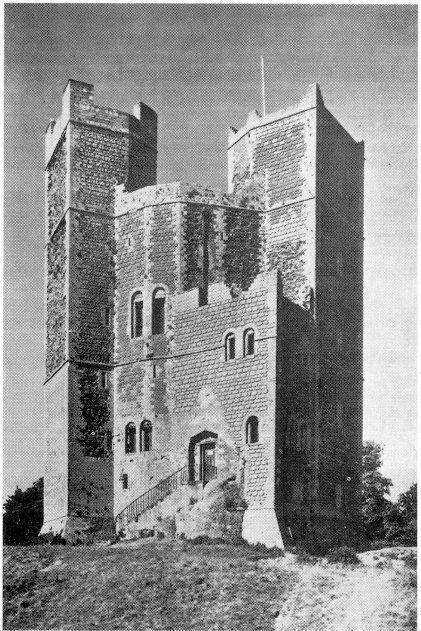

Orford Castle in Suffolk, one of the few secular buildings to remain much as it was in Eleanor’s time.

A. S. Kerning.

Finally, on 4 March, Richard and Eleanor sailed from Antwerp on board the

Trenchemer.

The royal admiral, Stephen of Turnham, who was commanding the little ship in person, had to employ experienced pilots to take her through the coastal islets and out into the estuary of the Scheldt. It was a long crossing, perhaps deliberately so, to avoid an ambush by Philip’s ships, and the

Trenchemer

was escorted by a large and redoubtable cog from the Cinque port of Rye. Richard and his mother landed at Sandwich on Sunday 13 March 1194. The king had been out of his kingdom for more than four years. It was the end of Eleanor’s regency in all but name.

‘Odysseus hath come, and hath got him to his own house.’

Homer,

The Odyssey

‘When his return from his long captivity had become an event rather wished than hoped for by his despairing subjects.’

Sir Walter Scott,

Ivanhoe

It was about nine o’clock in the morning when Richard and Eleanor sailed into Sandwich. The sun shone with such a wonderful red glow that men later said they had known that it announced the return of the king. He and his mother did not linger at Sandwich but rode straight to Canterbury, where they heard the monks sing Sunday mass and Richard prayed at the shrine of St Thomas in thanksgiving.

William of Newburgh, who remembered Richard’s return, wrote how, ‘The news of he coming of the king, so long and so desperately awaited, flew faster than the north wind’. Everyone was weary of insecure government, of the threat of being ruled by a man as giddy and feckless as count John. Yet not all rejoiced. One of John’s supporters, the castellan of St Michael’s Mount, actually died of fright on hearing the news. Most people were deliriously happy however, and folk memory seems to have preserved something of their happiness in the legend of Robin Hood. Perhaps Sir Walter Scott’s

Ivanhoe

is not so very far from the truth after all.

London prepared a magnificent reception for Richard,

Richard that robb’d the lion of his heart,

And fought the holy wars in Palestine.

The streets were decked with tapestries and green boughs. Ralph of Diceto, the dean of St Paul’s, who was almost certainly present, tells us that the king was ‘hailed with joy in the Strand’. In the city Richard was escorted by cheering crowds to St Paul’s, to be welcomed at the cathedral by a great throng of clergy. Some of the emperor’s German officials, in London to collect the remainder of the king’s ransom, were astonished by the general rejoicing and by the city’s obvious prosperity; they grumbled sourly that they had expected London to have been reduced to utter poverty from paying the money demanded by their master, and that had he realized how rich the country was, he would have asked for much more — the lamentations of the English had deceived him.

Richard then rode to the shrine of the martyred East Anglian king, St Edmund, at Bury St Edmunds, to give thanks to the man who appears to have been his favourite saint. Then he went to Nottingham. It was time for him to restore complete order in England and to deal with his brother John’s supporters.

Nottingham, one of John’s castles, was still holding out for its master, as was Tickhill in Northumberland, which had just been invested by the bishop of Durham. The two garrisons believed John’s lies and could not credit that the king had returned. When two of the knights inside Nottingham came out and saw that it really was Richard who was beseiging them, however, the castle surrendered at once, on 27 March. Tickhill had fallen a few days earlier and count John’s revolt was now completely crushed. In the ensuing great council at Nottingham — at which the queen mother was present — the king summoned his brother to appear before it within forty days or forfeit any right to succeed him in any of his territories. At the same time pope Celestine responded tardily to Eleanor’s appeals, and excommunicated both John and Philip of France for violating the ‘Truce of God’.

Meanwhile, on Low Sunday 17 April 1194, Richard was re-crowned at Winchester by archbishop Hubert Walter of Canterbury. Eleanor sat in the north transept of the cathedral on a special dais, surrounded by great ladies as though in one of her courts of love. She had been a good steward for her son; in bishop Stubb’s words: ‘Had it not been for her governing skill while Richard was in Palestine, and her influence on the continent … England would have been a prey to anarchy, and Normandy lost to the house of Anjou long before it was.’ Even if she herself was not re-crowned during the splendid ceremony, she sat there as queen of the English. Perhaps significantly, Berengaria was not present, but was far away in Poitou — no doubt to Eleanor’s complete satisfaction.

Despite the loyalty of the English, king Richard was anxious to return to his lands across the Channel, which he still loved best. After only a few weeks in England, having imposed even harsher taxes and sold yet more offices of state, he summoned his English knights — as many as one in every three — to follow him to France. On 22 April he left Winchester for Portsmouth, where he and his mother took ship, but only to be blown back by a fearful storm. Eventually it abated and on 12 May they were able to sail, with their fleet of one hundred vessels. The king had left England for the last time, although he was to reign for another five years. Nor would Eleanor herself ever return to England.

The royal couple landed at Barfleur, to receive the same ecstatic welcome from the Normans that they had been given by the English. Their progress through Normandy took them to Caen and Bayeux and then to Lisieux. At Lisieux they went to the house of the archdeacon, John of Alençon, to spend the night. That evening, much to his embarrassment, the archdeacon was informed by a servant that count John was waiting at his door ‘in a state of abject penitence’.

Philip of France had no use for ruined allies who had lost their lands, and the count had been brought very low. The prodigal son hoped that his mother might at least temper the wrath of his brother. The archdeacon went into Richard’s chamber, where the king was resting before supper, but was too nervous to speak. However Richard at once guessed that John was outside. ‘I know you have seen my brother’, he said; ‘he is wrong to be afraid — let him come in, without fear. After all, he is my brother.’ John entered, threw himself on the ground and crawled to the king’s feet, begging for forgiveness. ‘You are a mere child’, said Richard; ‘you have been ill advised and your counsellors shall pay for it.’ There was clearly an element of contempt in the king’s magnanimity: the ‘child’ was nearly thirty. Nevertheless Richard produced a fatted calf, in the shape of an enormous salmon that had just been presented to him by some loyal Norman, and ordered it to be cooked, telling John to make a good meal. The following year he gave him back Ireland, together with his county of Mortain and earldom of Gloucester, and also his honour of Eye. For the rest of the reign John remained loyal. In fact he owed his miraculous pardon to his mother: Roger of Howden makes it perfectly clear that it was due entirely to Eleanor’s pleading. As will be seen, her motives cannot have been wholly maternal.

Richard wanted to return to the Holy Land as soon as possible. Unfortunately Philip II’s determination to destroy the Angevin empire made it out of the question, and the king had to spend the rest of his life in almost unceasing frontier warfare with the French. Eleanor was by now too old and infirm to take part in these campaigns, as she might well have done had she been younger. Nevertheless, she must have had full confidence that Richard, who had the reputation of being the best soldier in western Europe, would prove more than a match for Philip of France.

Nor was her confidence misplaced. In June Richard hurled Philip out of Normandy, pursuing the French king with such speed that he had to hide in a roadside church. At the same time Richard restored order in Aquitaine, committing his usual atrocities when punishing rebellious barons, and also recovered eastern Touraine. Even if he did not regain all the territories that John had surrendered to the French, he had good reason for satisfaction when he concluded a twelve-month truce with Philip in November 1194.

John was by now fighting for his brother with enthusiasm. In May at Evreux he had 300 prisoners decapitated and stuck their heads on stakes around the citadel in a vain attempt to frighten it into surrender. Even king Richard was horrified, and rebuked the count.

The following summer the king’s former gaoler, the emperor Henry, proposed an alliance with Richard and sent him a golden crown as a token of his sincerity. He hoped to make France a vassal state of the empire and was considering a joint Anglo-German invasion. Hearing of these moves, Philip invaded Normandy once again. A meeting at Vaudreuil between the two kings ended in uproar when Philip accused Richard of breaking his word; the latter was so angry that he chased the Capetian for some miles. In the autumn Philip took Dieppe, burning the port and the English shipping in the harbour; Richard succeeded in capturing Issoudun in Berry. A new peace was then made, giving Philip the Vexin and the Auvergne, but Richard kept his gains.

One beneficiary from the peace negotiations during 1196 was Richard’s former betrothed, Alice of France, who was still unmarried at thirty-three in an era when royal princesses usually became brides at twelve or thirteen. She had been moved from her prison at Rouen to various castles, in case of any attempt at rescue. Her half-brother Philip, moved by considerations of strategy rather than affection, at last obtained her release and married her to count William of Ponthieu, whose county lay between Flanders and the northern Plantagenet lands; he was a usefully placed ally should king Richard and Baldwin of Flanders try to join forces. But at least Alice had acquired a husband whose rank was worthy of her. One cannot but suspect that Eleanor’s withdrawal from affairs of state at this time had saved Alice from perpetual imprisonment.