Eleanor of Aquitaine (36 page)

Read Eleanor of Aquitaine Online

Authors: Marion Meade

Fortunately for the Plantagenets, the strained situation in southern France at that time lent itself to the kind of venture they had in mind. Count Raymond of Toulouse was already at war with Count Raymond-Berengar of Barcelona, in addition to other dissatisfied vassals. Henry was not so crass or unskillful as to announce his designs on Toulouse openly; instead, sometime in April 1159, he and Eleanor casually drifted south through Aquitaine, winding up at Blaye in Gascony, where he formed an alliance with the count of Barcelona. To sweeten the pot and to make certain that Toulouse, once taken, did not stick to Raymond-Berengar’s fingers, Henry proposed a betrothal between his son, Richard, and Raymond’s daughter. Their partnership sealed, he sent a formal summons to the count of Toulouse, demanding surrender of the county in Eleanor’s name, which, of course, Count Raymond refused to do. For that matter, he responded by setting off an alarm and notifying his overlord and brother-in-law, Louis Capet, of the danger threatening.

If Louis received a rude shock from the man whom, just months earlier, he had called lovable, he did not allow it to affect his determinedly friendly policy toward the king of England. In 1159, he met with Henry in February and again in June, and although they could reach no agreement, they parted on warm terms. Louis was not the complete dupe he appeared. His hostility toward Henry had been, to a large extent, an expression of his resentment against Eleanor’s remarriage, and it had run contrary to the policy laid down by Abbot Suger, namely that the military inferiority of the French made cooperation with more powerful vassals the only sensible course. Although Louis had reached a stage of life where he preferred sensibility, nevertheless this new development created a dilemma. He could not very well contest Henry’s claim to Toulouse, because he himself had pressed it when he had been Eleanor’s husband. But neither could he accommodate Henry in his aspirations. For the moment, then, Louis stood tactfully aloof.

The early months of 1159 passed in a flurry of war fever. It is probable that Eleanor resided first at Rouen and later at Poitiers, which seems to have been headquarters for the mobilization. To be at home again must have filled her with pleasure; to be preparing for a war that would certainly be won was doubly exciting. For there was no doubt in her mind that her masterful husband, his military record unblemished save for that better-forgotten clash with the barbaric Welsh, would emerge victorious. On March 22, Henry had issued a summons to his vassals in England, Normandy, and Aquitaine to assemble at Poitiers on June 24. Not wishing to inconvenience England, so long a journey from Toulouse, he demanded only the services of his barons. Any English knight who did not wish to make the trip was assessed the sum of two marks, which would pay for a mercenary to fight in his place. In addition to the levy of this scutage, he exacted contributions from towns, sheriffs, Jewish moneylenders, and, much to their consternation and indignation, the clergy. Since the tax on the Church was collected by Becket, many concluded that it was his idea, which was probably untrue. Nevertheless, some years later bitter churchmen would remember and charge that Thomas had plunged a sword “into the vitals of Holy Mother Church with your own hand when you despoiled her of so many thousand marks for the expedition against Toulouse.” From laymen as well as churchmen, over eleven thousand pounds flowed into Henry’s treasury during the first half of 1159, enough to support a siege for at least five or six months.

On the appointed day, banners flouncing, the army left Poitiers in splendor. Altogether it was a brilliant and impressive parade of Henry’s vassals: the barons of England, Normandy, Anjou, Brittany, and Aquitaine; King Malcolm of Scotland, with an army that had required forty-five vessels to transport across the Channel; a showy contingent led by Thomas Becket, who, his ecclesiastical career rapidly fading into dim memory, headed not less than seven hundred knights of his own household, a tremendous force for that time and an indication of his extremely comfortable financial position. In addition, there was the count of Barcelona with some of the unhappy vassals of the count of Toulouse—William of Montpellier and Raymond Trencavel, viscount of Béziers and Carcassonne. The last time such a stupendous army had been seen in those parts was for a major Crusade.

By July 6, Henry’s army had encamped outside the high red walls of Toulouse and, siege engines and catapults in place, settled down for a lengthy stay. Medieval sieges were painfully boring for both besiegers and besieged. Those inside the walls of Toulouse grew claustrophobic and, to relieve their restlessness, would periodically sally forth to provoke Henry’s men into a clash of arrows and swords; then they would retreat inside the walls once more. There was little for Henry to do beyond preventing food or military help from reaching the Toulousains. July and August passed to the monotonous thumps of the engineers working their stone throwers. Henry, who hated inactivity, lacked the temperament to conduct a long siege, although he had brought with him his clerks and he kept busy with administrative chores, issuing writs, hearing judicial cases, and listening to subjects who had followed him to the gates of Toulouse to seek favors or appeal law cases. Toward the middle of September, the general ennui was enlivened by a strange sight. Louis Capet appeared before the city gates and requested permission to enter. Since he had brought no army—indeed he meekly declared that he had come only to safeguard his sister—he was permitted entry. But Louis’s unexpected arrival seemed to present Henry with a dilemma, or so he claimed. Within a week, he called off the siege, declaring that he had too great a reverence for the king of the Franks to attack a city in which his overlord resided. This, of course, was nonsense, for Henry had no reverence or even respect for Louis. Probably his real reasons for abandoning the siege were practical ones: The cost of feeding thousands was turning out to be an expensive business; the unsanitary conditions had caused an epidemic among his troops; and, of course, he was bored.

Henry’s decision to abandon the war sparked the first recorded disagreement between the king and his chancellor. Thirsty for military victory, horribly disappointed that he had lost the chance to lead his troops into a real battle, Thomas angrily argued against giving up. “Foolish superstition” was what he accused Henry of, declaring that Louis himself had forfeit any consideration by siding with Henry’s enemies. Not only that, but if Henry were to assault now, he could take Toulouse and make Louis a prisoner as well. Henry, barely controlling his temper, must have reiterated that he had, after all, done homage to Louis as his feudal overlord, and to attack his person would set a poor example for his own vassals. Without being explicit, the chroniclers hint that the disagreement between the two men grew heated. In any event, Henry left Toulouse on September 26, leaving behind his churlish chancellor, who then proceeded to assault several castles in the vicinity. By the time they next met, the clash would be seemingly forgotten.

It was a jubilant Raymond of Toulouse who watched the departure of that army whose vast stockpiles of arrows, siege machines, lances, and axes had rendered the chroniclers speechless. The duchess of Aquitaine had been foiled by his father, and now history had happily repeated itself. Someday Raymond would have revenge on Eleanor, but in the autumn of 1159, such events were still far in the future.

From a careful inspection of Henry’s itinerary in the remaining months of 1159, it appears that he traveled directly north from Toulouse, by way of Limoges, to Beauvais in Normandy, where Louis’s brother had been stirring up trouble along the border. One receives the distinct impression that he purposely avoided Poitiers, that after his argument with Becket he had small desire to face his wife. It is easy to guess Eleanor’s surprise and chagrin; this had been the second time that she had sent a husband against Toulouse, and both expeditions had ended in failure. In Louis’s case, defeat had been understandable, for he was hardly a warrior. But what excuse could she make for Henry? With his resources, in terms of both manpower and money, the capture of this single city, no matter how well defended, should have been an easy matter. It must have occurred to her that Henry was not the fighter that either his mother or father had been. He had spent half a year planning the war, raising a large army and vast sums of money, but when his opponent could not be intimidated, he had given up. Others might believe Henry’s reluctance to attack his liege lord the height of scrupulousness, but Eleanor saw it as a dent in the image of a man she had regarded as invincible.

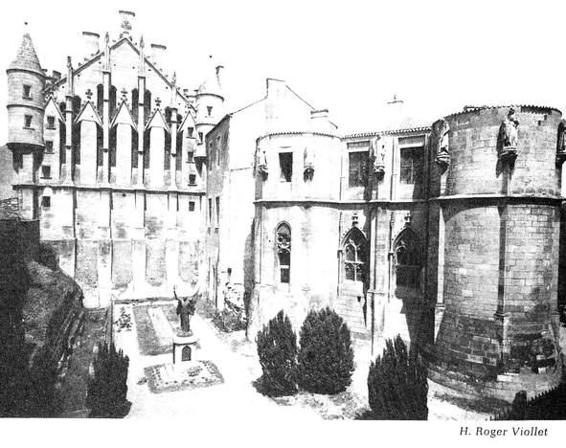

Above, the Palais de Justice, Poitiers, formerly Eleanor’s ancestral palace. On the

right

can be seen the Tour Maubergeonne, where Eleanor’s grandfather William IX lodged his mistress.

right

can be seen the Tour Maubergeonne, where Eleanor’s grandfather William IX lodged his mistress.

Right, Duke William IX of Aquitaine, a portrait from a fourteenth-century manuscript of troubadour poetry in the Bibliothèque Nationale

The figures representing a king and queen of Judah and believed to be likenesses of Eleanor and Louis were completed around 1150, shortly after the Second Crusade. From the west portal of Chartres Cathedral.

Rock crystal and pearl vase that Eleanor gave to Louis at the time of their marriage, now in the Louvre. The Latin inscription on the base reads that she gave it to her husband who presented it to Abbot Suger who in turn donated the vase to the Abbey of Saint-Denis. This is the only surviving object from Eleanor’s life.

Service de Documentation Photographique de

la

Reunion

des

Musées Nationaux

la

Reunion

des

Musées Nationaux

Other books

Doctor Who: The Massacre by John Lucarotti

The Ticket Out by Helen Knode

Miss Match by Lindzee Armstrong, Lydia Winters

Secrets on Saturday by Ann Purser

Rihanna by Sarah Oliver

Lorik (The Lorik Trilogy) by Neighbors, Toby

What Remains by Miller, Sandra

Love Revolution (Black Cat Records Shakespeare Inspired trilogy) by Mankin, Michelle

The Satanic Mechanic by Sally Andrew

The Girl in Blue by P.G. Wodehouse