Einstein (99 page)

Authors: Walter Isaacson

She succeeded in introducing him to the Soviet vice consul in New York, who was also a spy. But Einstein had no secrets to share, nor is there any evidence that he had any inclination at all to help the Soviets in any way, and he rebuffed her attempts to get him to visit Moscow.

The affair and potential security issue came to light not because of any FBI sleuthing but because a collection of nine amorous letters written by Einstein to Konenkova in the 1940s became public in 1998. In addition, a former Soviet spy, Pavel Sudoplatov, published a rather explosive but not totally reliable memoir in which he revealed that she was an agent code-named “Lukas.”

42

Einstein’s letters to Konenkova were written the year after she left America. Neither she nor Sudoplatov, nor anyone else, ever claimed that Einstein passed along any secrets, wittingly or unwittingly. However, the letters do make clear that, at age 66, he was still able to be amorous in prose and probably in person. “I recently washed my hair myself, but not with great success,” he said in one. “I am not as careful as you are.”

Even with his Russian lover, however, Einstein made clear that he was not an unalloyed lover of Russia. In one letter he denigrated Moscow’s militaristic May Day celebration, saying, “I watch these exaggerated patriotic exhibits with concern.”

43

Any expressions of excess nationalism and militarism had always made him uncomfortable, ever since he had watched German soldiers march by when he was a boy, and Russia’s were no different.

Despite Hoover’s suspicions, Einstein was a solid American citizen, and he considered his opposition to the wave of security and loyalty investigations to be a defense of the nation’s true values. Tolerance of free expression and independence of thought, he repeatedly argued, were the core values that Americans, to his delight, most cherished.

His first two presidential votes had been cast for Franklin Roosevelt, whom he publicly and enthusiastically endorsed. In 1948, dismayed by Harry Truman’s cold war policies, Einstein voted for the Progressive Party candidate Henry Wallace, who advocated greater cooperation with Russia and increased social welfare spending.

Throughout his life, Einstein was consistent in the fundamental premises of his politics. Ever since his student days in Switzerland, he had supported socialist economic policies tempered by a strong instinct for individual freedom, personal autonomy, democratic institutions, and protection of liberties. He befriended many of the democratic socialist leaders in Britain and America, such as Bertrand Russell and Norman Thomas, and in 1949 he wrote an influential essay for the inaugural issue of the

Monthly Review

titled “Why Socialism?”

In it he argued that unrestrained capitalism produced great disparities of wealth, cycles of boom and depression, and festering levels of unemployment. The system encouraged selfishness instead of cooperation, and acquiring wealth rather than serving others. People were educated for careers rather than for a love of work and creativity. And political parties became corrupted by political contributions from owners of great capital.

These problems could be avoided, Einstein argued in his article, through a socialist economy, if it guarded against tyranny and centralization of power. “A planned economy, which adjusts production to the needs of the community, would distribute the work to be done among all those able to work and would guarantee a livelihood to every man, woman, and child,” he wrote. “The education of the individual, in addition to promoting his own innate abilities, would attempt to develop in him a sense of responsibility for his fellow-men in place of the glorification of power and success in our present society.”

He added, however, that planned economies faced the danger of becoming oppressive, bureaucratic, and tyrannical, as had happened in communist countries such as Russia. “A planned economy may be accompanied by the complete enslavement of the individual,” he warned. It was therefore important for social democrats who believed in individual liberty to face two critical questions: “How is it possible, in view of the far-reaching centralization of political and economic power, to

prevent bureaucracy from becoming all-powerful and overweening? How can the rights of the individual be protected?”

44

That imperative—to protect the rights of the individual—was Einstein’s most fundamental political tenet. Individualism and freedom were necessary for creative art and science to flourish. Personally, politically, and professionally, he was repulsed by any restraints.

That is why he remained outspoken about racial discrimination in America. In Princeton during the 1940s, movie theaters were still segregated, blacks were not allowed to try on shoes or clothes at department stores, and the student newspaper declared that equal access for blacks to the university was “a noble sentiment but the time had not yet come.”

45

As a Jew who had grown up in Germany, Einstein was acutely sensitive to such discrimination. “The more I feel an American, the more this situation pains me,” he wrote in an essay called “The Negro Question” for

Pageant

magazine. “I can escape the feeling of complicity in it only by speaking out.”

46

Although he rarely accepted in person the many honorary degrees offered to him, Einstein made an exception when he was invited to Lincoln University, a black institution in Pennsylvania. Wearing his tattered gray herringbone jacket, he stood at a blackboard and went over his relativity equations for students, and then he gave a graduation address in which he denounced segregation as “an American tradition which is uncritically handed down from one generation to the next.”

47

As if to break the pattern, he met with the 6-year-old son of Horace Bond, the university’s president. That son, Julian, went on to become a Georgia state senator, one of the leaders of the civil rights movement, and chairman of the NAACP.

There was, however, one group for which Einstein could feel little tolerance after the war. “The Germans, as a whole nation, are responsible for these mass killings and should be punished as a people,” he declared.

48

When a German friend, James Franck, asked him at the end of 1945 to join an appeal calling for a lenient treatment of the German economy, Einstein angrily refused. “It is absolutely necessary to prevent the restoration of German industrial policy for many years,” he said. “Should your appeal be circulated, I shall do whatever I can to oppose

it.” When Franck persisted, Einstein became even more adamant. “The Germans butchered millions of civilians according to a well-prepared plan,” he wrote. “They would do it again if only they were able to. Not a trace of guilt or remorse is to be found among them.”

49

Einstein would not even permit his books to be sold in Germany again, nor would he allow his name to be placed back on the rolls of any German scientific society. “The crimes of the Germans are really the most abominable ever to be recorded in the history of the so-called civilized nations,” he wrote the physicist Otto Hahn. “The conduct of the German intellectuals—viewed as a class—was no better than that of the mob.”

50

Like many Jewish refugees, his feelings had a personal basis. Among those who suffered under the Nazis was his first cousin Roberto, son of Uncle Jakob. When German troops were retreating from Italy near the end of the war, they wantonly killed his wife and two daughters, then burned his home while he hid in the woods. Roberto wrote to Einstein, giving the horrible details, and committed suicide a year later.

51

The result was that Einstein’s national and tribal kinship became even more clear in his own mind. “I am not a German but a Jew by nationality,” he declared as the war ended.

52

Yet in ways that were subtle yet real, he had become an American as well. After settling in Princeton in 1933, he never once in the remaining twenty-two years of his life left the United States, except for the brief cruise to Bermuda that was necessary to launch his immigration process.

Admittedly, he was a somewhat contrarian citizen. But in that regard he was in the tradition of some venerable strands in the fabric of American character: fiercely protective of individual liberties, often cranky about government interference, distrustful of great concentrations of wealth, and a believer in the idealistic internationalism that gained favor among American intellectuals after both of the great wars of the twentieth century.

His penchant for dissent and nonconformity did not make him a worse American, he felt, but a better one. On the day in 1940 when he was naturalized as a citizen, Einstein had touched on these values in a

radio talk. After the war ended, Truman proclaimed a day in honor of all new citizens, and the judge who had naturalized Einstein sent out thousands of form letters inviting anyone he had sworn in to come to a park in Trenton to celebrate. To the judge’s amazement, ten thousand people showed up. Even more amazing, Einstein and his household decided to come down for the festivities. During the ceremony, he sat smiling and waving, with a young girl sitting on his lap, happy to be a small part of “I Am an American” Day.

53

LANDMARK

1948–1953

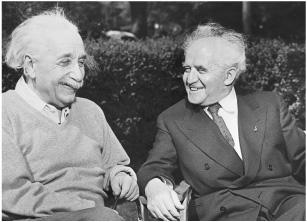

With Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion in Princeton, 1951

The problems of the world were important to Einstein, but the problems of the cosmos helped him to keep earthly matters in perspective. Even though he was producing little of scientific significance, physics rather than politics would remain his defining endeavor until the day he died. One morning when walking to work with his scientific assistant and fellow arms control advocate Ernst Straus, Einstein mused at their ability to divide their time between the two realms. “But our equations are much more important to me,” Einstein added. “Politics is for the present, while our equations are for eternity.”

1

Einstein had officially retired from the Institute for Advanced Study at the end of the war, when he turned 66. But he continued to

work in a small office there every day, and he was still able to enlist the aid of loyal assistants willing to pursue what had come to be considered his quaint quest for a unified field theory.

Each weekday, he would wake at a civilized hour, eat breakfast and read the papers, and then around ten walk slowly up Mercer Street to the Institute, trailing stories both real and apocryphal. His colleague Abraham Pais recalled “one occasion when a car hit a tree after the driver suddenly recognized the face of the beautiful old man walking along the street, the black woolen knit cap firmly planted on his long white hair.”

2

Soon after the war ended, J. Robert Oppenheimer came from Los Alamos to take over as director of the Institute. A brilliant, chain-smoking theoretical physicist, he proved charismatic and competent enough to be an inspiring leader for the scientists who built the atomic bomb. With his charm and biting wit, he tended to produce either acolytes or enemies, but Einstein fell into neither category. He and Oppenheimer viewed each other with a mixture of amusement and respect, which allowed them to develop a cordial though not close relationship.

3

When Oppenheimer first visited the Institute in 1935, he called it a “madhouse” with “solipsistic luminaries shining in separate and hapless desolation.” As for the greatest of these luminaries, Oppenheimer declared, “Einstein is completely cuckoo,” though he seemed to mean it in an affectionate way.

4

Once they became colleagues, Oppenheimer became more adroit at dealing with his luminous charges and his jabs became more subtle. Einstein, he declared, was “a landmark but not a beacon,” meaning he was admired for his great triumphs but attracted few apostles in his current endeavors, which was true. Years later, he provided another telling description of Einstein: “There was always in him a powerful purity at once childlike and profoundly stubborn.”

5

Einstein became a closer friend, and a walking partner, of another iconic figure at the Institute, the intensely introverted Kurt Gödel, a German-speaking mathematical logician from Brno and Vienna. Gödel was famous for his “incompleteness theory,” a pair of logical

proofs that purport to show that any useful mathematical system will have some propositions that cannot be proven true or false based on the postulates of that system.

Out of the supercharged German-speaking intellectual world, in which physics and mathematics and philosophy intertwined, three jarring theories of the twentieth century emerged: Einstein’s relativity, Heisenberg’s uncertainty, and Gödel’s incompleteness. The surface similarity of the three words, all of which conjure up a cosmos that is tentative and subjective, oversimplifies the theories and the connections between them. Nevertheless, they all seemed to have philosophical resonance, and this became the topic of discussion when Gödel and Einstein walked to work together.

6